N THE same month of Sha'ban that witnessed the indignities inflicted

upon the Bab in Tabriz, and the afflictions which befell Baha'u'llah and His companions

in Niyala, Mulla Husayn returned from the camp of Prince Hamzih Mirza to Mashhad,

from which place he was to proceed seven days later to Karbila accompanied by

whomsoever he might desire. The prince offered him a sum to defray the expenses

of his journey, an offer that he declined, sending the money back with a message

requesting him to expend it for the relief of the poor and needy. Abdu'l-'Ali

Khan likewise volunteered to provide all the requirements of Mulla Husayn's intended

pilgrimage, and expressed his eagerness to pay also the expenses of whomsoever

he might choose to accompany him. All that he accepted from him was a sword and

a horse, both of which he was destined to utilise with consummate bravery and

skill in repulsing the assaults of a treacherous enemy.

N THE same month of Sha'ban that witnessed the indignities inflicted

upon the Bab in Tabriz, and the afflictions which befell Baha'u'llah and His companions

in Niyala, Mulla Husayn returned from the camp of Prince Hamzih Mirza to Mashhad,

from which place he was to proceed seven days later to Karbila accompanied by

whomsoever he might desire. The prince offered him a sum to defray the expenses

of his journey, an offer that he declined, sending the money back with a message

requesting him to expend it for the relief of the poor and needy. Abdu'l-'Ali

Khan likewise volunteered to provide all the requirements of Mulla Husayn's intended

pilgrimage, and expressed his eagerness to pay also the expenses of whomsoever

he might choose to accompany him. All that he accepted from him was a sword and

a horse, both of which he was destined to utilise with consummate bravery and

skill in repulsing the assaults of a treacherous enemy.  My pen can never adequately describe the devotion

which Mulla Husayn had kindled in the hearts of the people of Mashhad, nor can

it seek to fathom the extent of his influence. His house, in those days, was continually

besieged by crowds of eager people who begged to be allowed to accompany him on

his contemplated journey. Mothers brought their sons, and sisters their brothers,

and tearfully implored him to accept them as their most cherished offerings on

the Altar of Sacrifice.

My pen can never adequately describe the devotion

which Mulla Husayn had kindled in the hearts of the people of Mashhad, nor can

it seek to fathom the extent of his influence. His house, in those days, was continually

besieged by crowds of eager people who begged to be allowed to accompany him on

his contemplated journey. Mothers brought their sons, and sisters their brothers,

and tearfully implored him to accept them as their most cherished offerings on

the Altar of Sacrifice.  Mulla Husayn was still in Mashhad when a messenger

arrived bearing to him the Bab's turban and conveying the news that a new name,

that of Siyyid Ali, had been conferred upon him by his Master. "Adorn your head,"

was the message, "with My green turban, the emblem of My lineage, and, with the

Black Standard(1) unfurled before

you,

Mulla Husayn was still in Mashhad when a messenger

arrived bearing to him the Bab's turban and conveying the news that a new name,

that of Siyyid Ali, had been conferred upon him by his Master. "Adorn your head,"

was the message, "with My green turban, the emblem of My lineage, and, with the

Black Standard(1) unfurled before

you,

As soon as that message reached him, Mulla

Husayn arose to execute the wishes of his Master. Leaving Mashhad for a place

situated at a farsang's(2)

distance from the city, he hoisted the Black Standard, placed the turban of the

Bab upon his head, assembled his companions, mounted his steed, and gave the signal

for their march to the Jaziriy-i-Khadra'. His companions, who were two hundred

and two in number, enthusiastically followed him. That memorable day was the nineteenth

of Sha'ban, in the year 1264 A.H.(3)

Wherever they tarried, at every village and hamlet through which they passed,

Mulla Husayn and his fellow-disciples would fearlessly proclaim the message of

the New Day, would invite the people to embrace its truth, and would select from

among those who responded to their call a few whom they would ask to join them

on their journey.

As soon as that message reached him, Mulla

Husayn arose to execute the wishes of his Master. Leaving Mashhad for a place

situated at a farsang's(2)

distance from the city, he hoisted the Black Standard, placed the turban of the

Bab upon his head, assembled his companions, mounted his steed, and gave the signal

for their march to the Jaziriy-i-Khadra'. His companions, who were two hundred

and two in number, enthusiastically followed him. That memorable day was the nineteenth

of Sha'ban, in the year 1264 A.H.(3)

Wherever they tarried, at every village and hamlet through which they passed,

Mulla Husayn and his fellow-disciples would fearlessly proclaim the message of

the New Day, would invite the people to embrace its truth, and would select from

among those who responded to their call a few whom they would ask to join them

on their journey.  In the town of Nishapur, Haji Abdu'l-Majid,

the father of Badi',(4) who

was a merchant of note, enlisted under the banner of Mulla Husayn. Though his

father enjoyed an unrivalled prestige as the owner of the best-known turquoise

mine of Nishapur, he, forsaking all the honours and material benefits that his

native town had conferred upon him, pledged his undivided loyalty to Mulla Husayn.

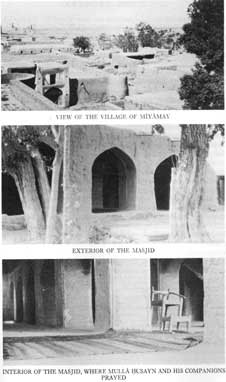

In the village of Miyamay, thirty among its inhabitants declared their faith

In the town of Nishapur, Haji Abdu'l-Majid,

the father of Badi',(4) who

was a merchant of note, enlisted under the banner of Mulla Husayn. Though his

father enjoyed an unrivalled prestige as the owner of the best-known turquoise

mine of Nishapur, he, forsaking all the honours and material benefits that his

native town had conferred upon him, pledged his undivided loyalty to Mulla Husayn.

In the village of Miyamay, thirty among its inhabitants declared their faith

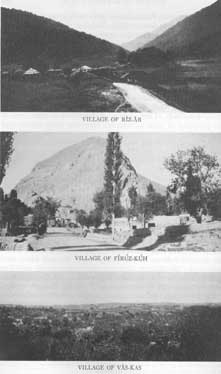

Arriving at Chashmih-'Ali, a place situated

near the town of Damghan and on the highroad to Mazindaran, Mulla Husayn decided

to break his journey and to tarry there for a few days. He encamped under the

shadow of a big tree, by the side of a running stream. "We stand at the parting

of the ways," he told his companions. "We shall await His decree as to which direction

we should take." Towards the end of the month of Shavval,(2)

a fierce gale arose and struck down a large branch of that tree; whereupon Mulla

Husayn observed: "The tree of the sovereignty of Muhammad Shah has, by the will

of God, been uprooted and hurled to the ground." On the third day after he had

uttered that prediction, a messenger, who was on his way to Mashhad, arrived from

Tihran and reported the death of his sovereign.(3)

The following day, the company determined to leave for Mazindaran. As their leader

arose to depart, he pointed in the direction of Mazindaran and said: "This is

the way that leads to our Karbila. Whoever is unprepared for the great trials

that lie before us, let him now repair to his home and give up the journey." He

several times repeated that warning, and, as he approached Savad-Kuh, explicitly

declared: "I, together with seventy-two of my companions, shall suffer death for

the sake of the Well-Beloved. Whoso is unable to renounce the world, let him now

at this very moment, depart, for later on he will be unable to escape." Twenty

of his companions chose to return, feeling themselves powerless to withstand the

trials to which their chief continually alluded.

Arriving at Chashmih-'Ali, a place situated

near the town of Damghan and on the highroad to Mazindaran, Mulla Husayn decided

to break his journey and to tarry there for a few days. He encamped under the

shadow of a big tree, by the side of a running stream. "We stand at the parting

of the ways," he told his companions. "We shall await His decree as to which direction

we should take." Towards the end of the month of Shavval,(2)

a fierce gale arose and struck down a large branch of that tree; whereupon Mulla

Husayn observed: "The tree of the sovereignty of Muhammad Shah has, by the will

of God, been uprooted and hurled to the ground." On the third day after he had

uttered that prediction, a messenger, who was on his way to Mashhad, arrived from

Tihran and reported the death of his sovereign.(3)

The following day, the company determined to leave for Mazindaran. As their leader

arose to depart, he pointed in the direction of Mazindaran and said: "This is

the way that leads to our Karbila. Whoever is unprepared for the great trials

that lie before us, let him now repair to his home and give up the journey." He

several times repeated that warning, and, as he approached Savad-Kuh, explicitly

declared: "I, together with seventy-two of my companions, shall suffer death for

the sake of the Well-Beloved. Whoso is unable to renounce the world, let him now

at this very moment, depart, for later on he will be unable to escape." Twenty

of his companions chose to return, feeling themselves powerless to withstand the

trials to which their chief continually alluded.

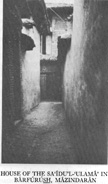

The news of their approach to the town of

Barfurush alarmed the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama'. The widespread and growing popularity

of Mulla Husayn, the circumstances attending his departure from Mashhad, the Black

Standard which waved before him--above all, the number, the discipline, and the

enthusiasm of his companions, combined to arouse the implacable hatred of that

cruel and overbearing mujtahid. He bade the crier summon the people of Barfurush

to the masjid and announce that a sermon of such momentous consequence was to

be delivered by him that no loyal adherent of Islam in that neighbourhood could

afford to ignore it. An immense crowd of men and women thronged the masjid, saw

him ascend the pulpit, fling his turban to the ground, tear open the neck of his

shirt, and bewail the plight into which the Faith had fallen. "Awake," he thundered

from the pulpit, for our enemies stand at our very doors, ready to wipe out all

that we cherish as pure and holy in Islam! Should we fail to resist them, none

will be left to survive their onslaught. He who is the leader of that band came

alone, one day, and attended my classes. He utterly ignored me and treated me

with marked disdain in the presence of my assembled disciples. As I refused to

accord him the honours which he expected, he angrily arose and flung me his challenge.

This man had the temerity, at a time when Muhammad Shah was seated upon his throne

and was at the height of his power, to assail me with so much bitterness. What

excesses this stirrer-up of mischief, who is now advancing at the head of his

savage band, will not commit now that the protecting hand of Muhammad Shah has

been suddenly withdrawn! It is the duty of all the inhabitants of Barfurush, both

young and old, both men and women, to arm themselves against these contemptible

wreckers of Islam, and by every means in their power to resist their onset. To-morrow,

at the hour of dawn, let all of you arise and march out to exterminate their forces."

The news of their approach to the town of

Barfurush alarmed the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama'. The widespread and growing popularity

of Mulla Husayn, the circumstances attending his departure from Mashhad, the Black

Standard which waved before him--above all, the number, the discipline, and the

enthusiasm of his companions, combined to arouse the implacable hatred of that

cruel and overbearing mujtahid. He bade the crier summon the people of Barfurush

to the masjid and announce that a sermon of such momentous consequence was to

be delivered by him that no loyal adherent of Islam in that neighbourhood could

afford to ignore it. An immense crowd of men and women thronged the masjid, saw

him ascend the pulpit, fling his turban to the ground, tear open the neck of his

shirt, and bewail the plight into which the Faith had fallen. "Awake," he thundered

from the pulpit, for our enemies stand at our very doors, ready to wipe out all

that we cherish as pure and holy in Islam! Should we fail to resist them, none

will be left to survive their onslaught. He who is the leader of that band came

alone, one day, and attended my classes. He utterly ignored me and treated me

with marked disdain in the presence of my assembled disciples. As I refused to

accord him the honours which he expected, he angrily arose and flung me his challenge.

This man had the temerity, at a time when Muhammad Shah was seated upon his throne

and was at the height of his power, to assail me with so much bitterness. What

excesses this stirrer-up of mischief, who is now advancing at the head of his

savage band, will not commit now that the protecting hand of Muhammad Shah has

been suddenly withdrawn! It is the duty of all the inhabitants of Barfurush, both

young and old, both men and women, to arm themselves against these contemptible

wreckers of Islam, and by every means in their power to resist their onset. To-morrow,

at the hour of dawn, let all of you arise and march out to exterminate their forces."

The entire congregation arose in response

to his call. His passionate eloquence, the undisputed authority he exercised over

them, and the dread of the loss of their own lives and property, combined to induce

the inhabitants of that town to make every possible preparation for the coming

The entire congregation arose in response

to his call. His passionate eloquence, the undisputed authority he exercised over

them, and the dread of the loss of their own lives and property, combined to induce

the inhabitants of that town to make every possible preparation for the coming

As soon as Mulla Husayn had determined to

pursue the way that led to Mazindaran, he, immediately after he had offered his

morning prayer, bade his companions discard all their possessions. "Leave behind

all your belongings," he urged them, "and content yourselves only with your steeds

and swords, that all may witness your renunciation of all earthly things, and

may realise that this little band of God's chosen companions has no desire to

safeguard its own property, much less to covet the property of others." Instantly

they all obeyed and, unburdening their steeds, arose and joyously followed him.

The father of Badi' was the first to throw aside his satchel, which contained

a considerable amount of turquoise which he had brought with him from the mine

that belonged to his father. One word from Mulla Husayn proved sufficient to induce

him to fling by the road-side what was undoubtedly his most treasured possession,

and to cling to the desire of his leader.

As soon as Mulla Husayn had determined to

pursue the way that led to Mazindaran, he, immediately after he had offered his

morning prayer, bade his companions discard all their possessions. "Leave behind

all your belongings," he urged them, "and content yourselves only with your steeds

and swords, that all may witness your renunciation of all earthly things, and

may realise that this little band of God's chosen companions has no desire to

safeguard its own property, much less to covet the property of others." Instantly

they all obeyed and, unburdening their steeds, arose and joyously followed him.

The father of Badi' was the first to throw aside his satchel, which contained

a considerable amount of turquoise which he had brought with him from the mine

that belonged to his father. One word from Mulla Husayn proved sufficient to induce

him to fling by the road-side what was undoubtedly his most treasured possession,

and to cling to the desire of his leader.  At a farsang's(2)

distance from Barfurush, Mulla Husayn and his companions encountered their enemies.

A multitude of people, fully equipped with arms and ammunition, had gathered,

and blocked their way. A fierce expression of savagery rested upon their countenances,

and the foulest

At a farsang's(2)

distance from Barfurush, Mulla Husayn and his companions encountered their enemies.

A multitude of people, fully equipped with arms and ammunition, had gathered,

and blocked their way. A fierce expression of savagery rested upon their countenances,

and the foulest

Unsheathing his sword and spurring on his

charger into the midst of the enemy, Mulla Husayn pursued, with marvellous intrepidity,

the assailant of his fallen companion. His opponent, who was afraid to face him,

took refuge behind a tree and, holding aloft his musket, sought to shield himself.

Mulla Husayn immediately recognised him, rushed

Unsheathing his sword and spurring on his

charger into the midst of the enemy, Mulla Husayn pursued, with marvellous intrepidity,

the assailant of his fallen companion. His opponent, who was afraid to face him,

took refuge behind a tree and, holding aloft his musket, sought to shield himself.

Mulla Husayn immediately recognised him, rushed

I myself, when in Tihran, in the year 1265

A.H.,(2) a month after the

conclusion of the memorable struggle of Shaykh Tabarsi, heard Mirza Ahmad relate

the circumstances of this incident in the presence of a number of believers, among

whom were Mirza Muhammad-Husayn-i-Hakamiy-i-Kirmani, Haji Mulla Isma'il-i-Farahani,

Mirza Habibu'llah-i-Isfahani, and Siyyid Muhammad-i-Isfahani.

I myself, when in Tihran, in the year 1265

A.H.,(2) a month after the

conclusion of the memorable struggle of Shaykh Tabarsi, heard Mirza Ahmad relate

the circumstances of this incident in the presence of a number of believers, among

whom were Mirza Muhammad-Husayn-i-Hakamiy-i-Kirmani, Haji Mulla Isma'il-i-Farahani,

Mirza Habibu'llah-i-Isfahani, and Siyyid Muhammad-i-Isfahani.  When, at a later time, I visited

Khurasan and was staying at the home of Mulla Sadiq-i-Khurasani in Mashhad, where

I had been invited to teach the Cause, I asked Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi,

When, at a later time, I visited

Khurasan and was staying at the home of Mulla Sadiq-i-Khurasani in Mashhad, where

I had been invited to teach the Cause, I asked Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi,

"So convincing a testimony of the strength

of his opponent constituted, in the eyes of the Amir-Nizam, a challenge

"So convincing a testimony of the strength

of his opponent constituted, in the eyes of the Amir-Nizam, a challenge

Such a remarkable display of dexterity and

strength could not fail to attract the attention of a considerable number of observers

whose minds had remained, as yet, untainted by prejudice or malice. It evoked

the enthusiasm of poets who, in different cities of Persia, were moved to celebrate

the exploits of the author of so daring an act. Their poems helped to diffuse

the knowledge, and to immortalise the memory, of that mighty deed. Among those

who paid their tribute to the valour of Mulla Husayn was a certain Rida-Quli Khan-i-Lalih-Bashi,

who, in the "Tarikh-i-Nasiri," lavished his praise on the prodigious strength

and the unrivalled skill which had characterised that stroke.

Such a remarkable display of dexterity and

strength could not fail to attract the attention of a considerable number of observers

whose minds had remained, as yet, untainted by prejudice or malice. It evoked

the enthusiasm of poets who, in different cities of Persia, were moved to celebrate

the exploits of the author of so daring an act. Their poems helped to diffuse

the knowledge, and to immortalise the memory, of that mighty deed. Among those

who paid their tribute to the valour of Mulla Husayn was a certain Rida-Quli Khan-i-Lalih-Bashi,

who, in the "Tarikh-i-Nasiri," lavished his praise on the prodigious strength

and the unrivalled skill which had characterised that stroke.  I ventured to ask Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi

whether he was aware that in the "Nasikhu't-Tavarikh" mention had been made of

the fact that Mulla Husayn had, in his early youth, been instructed in the art

of swordsmanship, that he had acquired his proficiency only after a considerable

period of training. "This is sheer fabrication," affirmed Mulla Muhammad. "I have

known him from his childhood, and have been associated with him, as a classmate

and friend, for a long time. I have never known him to be possessed of such strength

and power. I even deem myself superior in vigour and bodily endurance. His hand

trembled as he wrote, and he often expressed his inability to write as fully and

as frequently as he wished. He was greatly handicapped in this respect, and he

continued to suffer from its effects until his journey to Mazindaran. The moment

he unsheathed

I ventured to ask Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi

whether he was aware that in the "Nasikhu't-Tavarikh" mention had been made of

the fact that Mulla Husayn had, in his early youth, been instructed in the art

of swordsmanship, that he had acquired his proficiency only after a considerable

period of training. "This is sheer fabrication," affirmed Mulla Muhammad. "I have

known him from his childhood, and have been associated with him, as a classmate

and friend, for a long time. I have never known him to be possessed of such strength

and power. I even deem myself superior in vigour and bodily endurance. His hand

trembled as he wrote, and he often expressed his inability to write as fully and

as frequently as he wished. He was greatly handicapped in this respect, and he

continued to suffer from its effects until his journey to Mazindaran. The moment

he unsheathed

|

his sword,

however, to repulse that savage attack, a mysterious power seemed to have

suddenly transformed him. In all subsequent encounters, he was seen to be

the first to spring forward and spur on his charger into the camp of the

aggressor. Unaided, he would face and fight the combined forces of his opponents

and would himself achieve the victory. We, who followed him in the rear,

had to content ourselves with those who had already been disabled and were

weakened by the blows they had sustained. His name alone was sufficient

to strike terror into the hearts of his adversaries. They fled at mention

of him; they trembled at his approach. Even those who were his constant

companions were mute with wonder before him. We were stunned by the display

of his stupendous force, his indomitable will and complete intrepidity.

We were all convinced that he had ceased to be the Mulla Husayn whom we

had known, and that in him resided a spirit which God alone could bestow."

This same Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi related

to me the following: "Mulla Husayn had no sooner dealt his memorable blow

to his adversary than he disappeared from our sight. We knew not whither

he had gone. His attendant, Qambar-'Ali, alone could follow him. He subsequently

informed us that his master threw himself headlong upon his enemies, and

was able with a single stroke of his sword to strike down each of those

who dared assail him. Unmindful of the bullets that rained upon him, he

forced his way through the ranks of the enemy and headed for Barfurush.

He rode straight to the residence of the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama', thrice made the

circuit of his house, and cried out: `Let that contemptible This same Mirza Muhammad-i-Furughi related

to me the following: "Mulla Husayn had no sooner dealt his memorable blow

to his adversary than he disappeared from our sight. We knew not whither

he had gone. His attendant, Qambar-'Ali, alone could follow him. He subsequently

informed us that his master threw himself headlong upon his enemies, and

was able with a single stroke of his sword to strike down each of those

who dared assail him. Unmindful of the bullets that rained upon him, he

forced his way through the ranks of the enemy and headed for Barfurush.

He rode straight to the residence of the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama', thrice made the

circuit of his house, and cried out: `Let that contemptible |

The voice of Mulla Husayn drowned

the clamour of the multitude. The inhabitants of Barfurush surrendered and soon

raised the cry, "Peace, peace!" No sooner had the voice of surrender been raised

than the acclamations of the followers of Mulla Husayn, who at that moment were

seen galloping towards Barfurush, were heard from every side. The cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!"(1) which they

shouted at the top of their voices, struck dismay into the hearts of those who

heard it. The companions of Mulla Husayn, who had abandoned the hope of again

finding him alive, were greatly surprised when they saw him seated erect upon

his horse, unhurt and unaffected by the fierceness of that onset. Each reverently

approached him and kissed his stirrups.

The voice of Mulla Husayn drowned

the clamour of the multitude. The inhabitants of Barfurush surrendered and soon

raised the cry, "Peace, peace!" No sooner had the voice of surrender been raised

than the acclamations of the followers of Mulla Husayn, who at that moment were

seen galloping towards Barfurush, were heard from every side. The cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!"(1) which they

shouted at the top of their voices, struck dismay into the hearts of those who

heard it. The companions of Mulla Husayn, who had abandoned the hope of again

finding him alive, were greatly surprised when they saw him seated erect upon

his horse, unhurt and unaffected by the fierceness of that onset. Each reverently

approached him and kissed his stirrups.  On the afternoon of that day, the peace which

the inhabitants of Barfurush had implored was granted. To the crowd which had

gathered about him, Mulla Husayn spoke these words: "O followers of the Prophet

of God, and shi'ahs of the imams of His Faith! Why have you risen against us?

Why deem the shedding of our blood an act meritorious in the sight of God? Did

we ever repudiate the truth of your Faith? Is this the hospitality which the Apostle

of God has enjoined His followers to accord to both the faithful and the infidel?

What have we done to merit such condemnation on your part? Consider: I alone,

with no other weapon than my sword, have been able to face the rain of bullets

which the inhabitants of Barfurush have poured upon me, and have emerged unscathed

from the midst of the fire with which you have besieged me. Both my person and

my horse have escaped unhurt from your overwhelming attack. Except for the slight

scratch which I received on my face, you have

On the afternoon of that day, the peace which

the inhabitants of Barfurush had implored was granted. To the crowd which had

gathered about him, Mulla Husayn spoke these words: "O followers of the Prophet

of God, and shi'ahs of the imams of His Faith! Why have you risen against us?

Why deem the shedding of our blood an act meritorious in the sight of God? Did

we ever repudiate the truth of your Faith? Is this the hospitality which the Apostle

of God has enjoined His followers to accord to both the faithful and the infidel?

What have we done to merit such condemnation on your part? Consider: I alone,

with no other weapon than my sword, have been able to face the rain of bullets

which the inhabitants of Barfurush have poured upon me, and have emerged unscathed

from the midst of the fire with which you have besieged me. Both my person and

my horse have escaped unhurt from your overwhelming attack. Except for the slight

scratch which I received on my face, you have

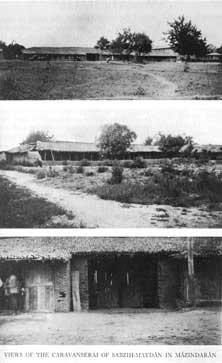

Immediately afterwards, Mulla Husayn proceeded

to the caravanserai of Sabzih-Maydan. He dismounted and, standing at the entrance

of the inn, awaited the arrival of his companions. As soon as they had gathered

and been accommodated in that place, he sent for bread and water. Those who had

been commissioned to fetch them returned empty-handed, and informed him that they

had been unable to procure either bread from the baker or water from the public

square. "You have exhorted us," they told him, "to put our trust in God and to

resign ourselves to His will. `Nothing can befall us but what God hath destined

for us. Our liege Lord is He; and on God let the faithful trust!'"(1)

Immediately afterwards, Mulla Husayn proceeded

to the caravanserai of Sabzih-Maydan. He dismounted and, standing at the entrance

of the inn, awaited the arrival of his companions. As soon as they had gathered

and been accommodated in that place, he sent for bread and water. Those who had

been commissioned to fetch them returned empty-handed, and informed him that they

had been unable to procure either bread from the baker or water from the public

square. "You have exhorted us," they told him, "to put our trust in God and to

resign ourselves to His will. `Nothing can befall us but what God hath destined

for us. Our liege Lord is He; and on God let the faithful trust!'"(1)

Mulla Husayn ordered that the gates of the

caravanserai be closed. Assembling his companions, he begged them to remain gathered

in his presence until the hour of sunset. As the evening approached,

he asked whether any among them would be willing to arise and, renouncing his

life for the sake of his Faith, ascend to the roof of the caravanserai and sound

the adhan.(2) A youth gladly

responded. No sooner had the opening words of "Allah-u-Akbar" dropped from his

lips than a bullet suddenly struck him and immediately caused his death. "Let

another one among you arise,"

Mulla Husayn ordered that the gates of the

caravanserai be closed. Assembling his companions, he begged them to remain gathered

in his presence until the hour of sunset. As the evening approached,

he asked whether any among them would be willing to arise and, renouncing his

life for the sake of his Faith, ascend to the roof of the caravanserai and sound

the adhan.(2) A youth gladly

responded. No sooner had the opening words of "Allah-u-Akbar" dropped from his

lips than a bullet suddenly struck him and immediately caused his death. "Let

another one among you arise,"

The fall of his third companion

decided Mulla Husayn to throw open the gate of the caravanserai, and to arise,

together with his friends, to repulse this unexpected attack from a treacherous

enemy. Leaping on horseback, he gave the signal to charge upon the assailants

who had massed before the gates and had filled the Sabzih-Maydan. Sword in hand,

and followed by his companions, he succeeded in decimating the forces that had

been arrayed against him. Those few who had escaped their swords fled before them

in panic, again pleading for peace, again imploring mercy. With the approach of

evening, the entire crowd had vanished. The Sabzih-Maydan, which a few hours before

overflowed with a seething mass of opponents, was now deserted. The clamour of

the multitude was stilled. Bestrewn with the bodies of the slain, the Maydan and

its surroundings offered a sad and moving spectacle, a scene which bore witness

to the victory of God over His enemies.

The fall of his third companion

decided Mulla Husayn to throw open the gate of the caravanserai, and to arise,

together with his friends, to repulse this unexpected attack from a treacherous

enemy. Leaping on horseback, he gave the signal to charge upon the assailants

who had massed before the gates and had filled the Sabzih-Maydan. Sword in hand,

and followed by his companions, he succeeded in decimating the forces that had

been arrayed against him. Those few who had escaped their swords fled before them

in panic, again pleading for peace, again imploring mercy. With the approach of

evening, the entire crowd had vanished. The Sabzih-Maydan, which a few hours before

overflowed with a seething mass of opponents, was now deserted. The clamour of

the multitude was stilled. Bestrewn with the bodies of the slain, the Maydan and

its surroundings offered a sad and moving spectacle, a scene which bore witness

to the victory of God over His enemies.  So startling a victory(1)

induced a number of the nobles and chiefs of the people to intervene and beseech

the mercy of Mulla Husayn on behalf of their fellow-citizens. They came on foot

to submit to him their petition. "God is our witness," they pleaded, "that we

harbour no intention but

So startling a victory(1)

induced a number of the nobles and chiefs of the people to intervene and beseech

the mercy of Mulla Husayn on behalf of their fellow-citizens. They came on foot

to submit to him their petition. "God is our witness," they pleaded, "that we

harbour no intention but

As soon as they had made their declaration,

their friends who had gone to fetch food for the companions and fodder for their

horses, arrived. Mulla Husayn bade his fellow-believers break their fast, inasmuch

as none of them that day, which was Friday, the twelfth of the month of Dhi'l-Qa'dih,(1)

had taken any meat or drink since the hour of dawn. So great was the number of

notables and their attendants that had crowded into the caravanserai that day

that neither he nor any of his companion had partaken of the tea which they had

offered to their visitors.

As soon as they had made their declaration,

their friends who had gone to fetch food for the companions and fodder for their

horses, arrived. Mulla Husayn bade his fellow-believers break their fast, inasmuch

as none of them that day, which was Friday, the twelfth of the month of Dhi'l-Qa'dih,(1)

had taken any meat or drink since the hour of dawn. So great was the number of

notables and their attendants that had crowded into the caravanserai that day

that neither he nor any of his companion had partaken of the tea which they had

offered to their visitors.  That night, about four hours after sunset,

Mulla Husayn, together with his friends, dined in the company of Abbas-Quli Khan

and Haji Mustafa Khan. In the middle of that same night, the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama'

summoned Khusraw-i-Qadi-Kala'i and confidentially intimated to him his desire

that, at any time or place he himself might decide, the entire property of the

party which had been entrusted to his charge should be seized, and that they themselves,

without a single exception, should be put to death. "Are these not the followers

of Islam?" Khusraw observed. "Have not these same people, as I have already learned,

preferred to sacrifice three of their companions rather than leave unfinished

the call to prayer which they had raised? How could we, who cherish such designs

and perpetrate such acts, be regarded as worthy of that name?" That shameless

miscreant insisted that his orders be faithfully obeyed. "Slay them," he said,

as he pointed with his finger to his neck, "and be not afraid. I hold myself responsible

for your act. I will, on the Day of Judgment, be answerable to God in your name.

We, who wield the sceptre of authority, are surely better informed than you, and

can better judge how best to extirpate this heresy."

That night, about four hours after sunset,

Mulla Husayn, together with his friends, dined in the company of Abbas-Quli Khan

and Haji Mustafa Khan. In the middle of that same night, the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama'

summoned Khusraw-i-Qadi-Kala'i and confidentially intimated to him his desire

that, at any time or place he himself might decide, the entire property of the

party which had been entrusted to his charge should be seized, and that they themselves,

without a single exception, should be put to death. "Are these not the followers

of Islam?" Khusraw observed. "Have not these same people, as I have already learned,

preferred to sacrifice three of their companions rather than leave unfinished

the call to prayer which they had raised? How could we, who cherish such designs

and perpetrate such acts, be regarded as worthy of that name?" That shameless

miscreant insisted that his orders be faithfully obeyed. "Slay them," he said,

as he pointed with his finger to his neck, "and be not afraid. I hold myself responsible

for your act. I will, on the Day of Judgment, be answerable to God in your name.

We, who wield the sceptre of authority, are surely better informed than you, and

can better judge how best to extirpate this heresy."  At the hour of sunrise, Abbas-Quli Khan asked

that Khusraw be conducted into his presence, and bade him exercise the utmost

consideration towards Mulla Husayn and his companions, to ensure their safe passage

through Shir-Gah, and to refuse whatever rewards they might wish to offer him.

At the hour of sunrise, Abbas-Quli Khan asked

that Khusraw be conducted into his presence, and bade him exercise the utmost

consideration towards Mulla Husayn and his companions, to ensure their safe passage

through Shir-Gah, and to refuse whatever rewards they might wish to offer him.

When Khusraw was taken by Abbas-Quli Khan

and Haji Mustafa Khan and other representative leaders of Barfurush into the presence

of Mulla Husayn and was introduced to him, the latter remarked: "`If ye do well,

it will redound to your own advantage; and if ye do evil, the evil will return

upon you."(1) If this man

should treat us well, great shall be his reward; and if he act treacherously towards

us, great shall be his punishment. To God would we commit our Cause, and to His

will are we wholly resigned."

When Khusraw was taken by Abbas-Quli Khan

and Haji Mustafa Khan and other representative leaders of Barfurush into the presence

of Mulla Husayn and was introduced to him, the latter remarked: "`If ye do well,

it will redound to your own advantage; and if ye do evil, the evil will return

upon you."(1) If this man

should treat us well, great shall be his reward; and if he act treacherously towards

us, great shall be his punishment. To God would we commit our Cause, and to His

will are we wholly resigned."  Mulla Husayn spoke these words and gave the

signal for departure. Once more Qambar-'Ali was heard to raise the call of his

master, "Mount your steeds, O heroes of God!"-- a summons which he invariably

called out on such occasions. At the sound of those words, they all hurried to

their steeds. A detachment of Khusraw's horsemen marched before them. They were

immediately followed by Khusraw and Mulla Husayn, who rode abreast in the centre

of the company. In their rear followed the rest of the companions, and on their

right and left marched the remainder of the hundred horsemen whom Khusraw had

armed as willing instruments for the execution of his design. It had been agreed

that the party should start early in the morning from Barfurush and arrive on

the same day at noon at Shir-Gah. Two hours after sunrise, they started for their

destination. Khusraw intentionally took the way of the forest, a route which he

thought would better serve his purpose.

Mulla Husayn spoke these words and gave the

signal for departure. Once more Qambar-'Ali was heard to raise the call of his

master, "Mount your steeds, O heroes of God!"-- a summons which he invariably

called out on such occasions. At the sound of those words, they all hurried to

their steeds. A detachment of Khusraw's horsemen marched before them. They were

immediately followed by Khusraw and Mulla Husayn, who rode abreast in the centre

of the company. In their rear followed the rest of the companions, and on their

right and left marched the remainder of the hundred horsemen whom Khusraw had

armed as willing instruments for the execution of his design. It had been agreed

that the party should start early in the morning from Barfurush and arrive on

the same day at noon at Shir-Gah. Two hours after sunrise, they started for their

destination. Khusraw intentionally took the way of the forest, a route which he

thought would better serve his purpose.  As soon as they had penetrated it, he gave

the signal for attack. His men fiercely threw themselves upon the companions,

seized their property, killed a number, among whom was the brother of Mulla Sadiq,

and captured the rest. As soon as the cry of agony and distress reached his ears,

Mulla Husayn halted, and, alighting from his horse, protested against Khusraw's

treacherous behaviour. "The hour of midday is long past," he told him; "we still

have not attained

As soon as they had penetrated it, he gave

the signal for attack. His men fiercely threw themselves upon the companions,

seized their property, killed a number, among whom was the brother of Mulla Sadiq,

and captured the rest. As soon as the cry of agony and distress reached his ears,

Mulla Husayn halted, and, alighting from his horse, protested against Khusraw's

treacherous behaviour. "The hour of midday is long past," he told him; "we still

have not attained

Mulla Husayn was still in the act of prayer

when the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman"(3)

was raised again by his companions. They threw themselves upon their treacherous

assailants and in one onslaught struck them all down except the attendant who

had prepared the qulayn. Affrighted and defenceless, he fell at the feet of Mulla

Husayn and implored his aid. He was given the bejewelled qulayn which belonged

to his master and was bidden to return to Barfurush and recount to Abbas-Quli

Khan all that he had witnessed. "Tell him," said Mulla Husayn, "how faithfully

Khusraw discharged his mission. That false miscreant foolishly imagined that my

mission had come to an end, that both my sword and my horse had fulfilled their

function. Little did he know that their work had but just begun, that until the

services which they can render are entirely accomplished, neither his power nor

the power of any man beside him can wrest them from me."

Mulla Husayn was still in the act of prayer

when the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman"(3)

was raised again by his companions. They threw themselves upon their treacherous

assailants and in one onslaught struck them all down except the attendant who

had prepared the qulayn. Affrighted and defenceless, he fell at the feet of Mulla

Husayn and implored his aid. He was given the bejewelled qulayn which belonged

to his master and was bidden to return to Barfurush and recount to Abbas-Quli

Khan all that he had witnessed. "Tell him," said Mulla Husayn, "how faithfully

Khusraw discharged his mission. That false miscreant foolishly imagined that my

mission had come to an end, that both my sword and my horse had fulfilled their

function. Little did he know that their work had but just begun, that until the

services which they can render are entirely accomplished, neither his power nor

the power of any man beside him can wrest them from me."  As the night was approaching, the party decided

to tarry in that spot until the hour of dawn. At daybreak, after Mulla Husayn

had offered his prayer, he gathered his companions

As the night was approaching, the party decided

to tarry in that spot until the hour of dawn. At daybreak, after Mulla Husayn

had offered his prayer, he gathered his companions

On the very day of their arrival, which was

the fourteenth of Dhi'l-Qa'dih,(1)

Mulla Husayn gave Mirza Muhammad-Baqir, who had built the Babiyyih, the preliminary

instruc-

On the very day of their arrival, which was

the fourteenth of Dhi'l-Qa'dih,(1)

Mulla Husayn gave Mirza Muhammad-Baqir, who had built the Babiyyih, the preliminary

instruc-

Fearing that their assailants might again

turn on them and resort to a general massacre, they pursued them until they reached

a village which they thought to be the village of Qadi-Kala. At the sight of them,

all the men fled in wild terror. The mother of Nazar Khan, the owner of the village,

was inadvertently killed in the darkness of the night, amid the confusion that

ensued. The outcries of the women, who were violently protesting that they had

no connection whatever with the people of Qadi-Kala, soon reached the ears of

Mirza Muhammad-Taqi, who immediately ordered his companions to withhold their

hands until they ascertained the name and character of the place. They soon found

out that the village belonged to Nazar Khan and that the woman who had lost her

life was his mother. Greatly distressed at the discovery of so grievous a mistake

on the part of his companions, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi sorrowfully exclaimed: "We

did not intend to molest either the men or the women of this village. Our sole

purpose was to curb the violence of the people of Qadi-Kala, who were about to

put us all to death." He apologised earnestly for the pitiful tragedy which his

companions had unwittingly enacted.

Fearing that their assailants might again

turn on them and resort to a general massacre, they pursued them until they reached

a village which they thought to be the village of Qadi-Kala. At the sight of them,

all the men fled in wild terror. The mother of Nazar Khan, the owner of the village,

was inadvertently killed in the darkness of the night, amid the confusion that

ensued. The outcries of the women, who were violently protesting that they had

no connection whatever with the people of Qadi-Kala, soon reached the ears of

Mirza Muhammad-Taqi, who immediately ordered his companions to withhold their

hands until they ascertained the name and character of the place. They soon found

out that the village belonged to Nazar Khan and that the woman who had lost her

life was his mother. Greatly distressed at the discovery of so grievous a mistake

on the part of his companions, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi sorrowfully exclaimed: "We

did not intend to molest either the men or the women of this village. Our sole

purpose was to curb the violence of the people of Qadi-Kala, who were about to

put us all to death." He apologised earnestly for the pitiful tragedy which his

companions had unwittingly enacted.  Nazar Khan, who in the meantime had concealed

himself in his house, was convinced of the sincerity of the regrets expressed

by Mirza Muhammad-Taqi. Though suffering from this grievous loss, he was moved

to call upon him and to invite him to his home. He even asked Mirza Muhammad-Taqi

to introduce him to Mulla Husayn, and expressed a keen desire to be made acquainted

with the precepts of a Cause that could kindle such fervour in the breasts of

its adherents.

Nazar Khan, who in the meantime had concealed

himself in his house, was convinced of the sincerity of the regrets expressed

by Mirza Muhammad-Taqi. Though suffering from this grievous loss, he was moved

to call upon him and to invite him to his home. He even asked Mirza Muhammad-Taqi

to introduce him to Mulla Husayn, and expressed a keen desire to be made acquainted

with the precepts of a Cause that could kindle such fervour in the breasts of

its adherents.  At the hour of dawn, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi,

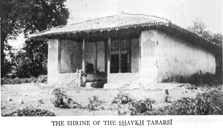

accompanied by Nazar Khan, arrived at the shrine of Shaykh Tabarsi, and found

Mulla Husayn leading the congregational prayer. Such was the rapture that glowed

upon his countenance

At the hour of dawn, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi,

accompanied by Nazar Khan, arrived at the shrine of Shaykh Tabarsi, and found

Mulla Husayn leading the congregational prayer. Such was the rapture that glowed

upon his countenance

Mulla Husayn ordered his companions to commence

the building of the fort which had been designed. To every group he assigned a

section of the work, and encouraged them to hasten its completion. In the course

of these operations, they were continually harassed by the people of the neighbouring

villages, who, at the persistent instigations of the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama', marched

out and fell upon them. Every attack of the enemy ended in failure and shame.

Undeterred by the fierceness of their repeated onsets, the companions valiantly

withstood their assaults until they had succeeded in subjugating temporarily the

forces which had hemmed them in on every side. When the work of construction was

completed, Mulla Husayn undertook the necessary preparations for the siege which

the fort was destined to sustain, and provided, despite the obstacles which stood

in his way, whatever seemed essential for the safety of its occupants.

Mulla Husayn ordered his companions to commence

the building of the fort which had been designed. To every group he assigned a

section of the work, and encouraged them to hasten its completion. In the course

of these operations, they were continually harassed by the people of the neighbouring

villages, who, at the persistent instigations of the Sa'idu'l-'Ulama', marched

out and fell upon them. Every attack of the enemy ended in failure and shame.

Undeterred by the fierceness of their repeated onsets, the companions valiantly

withstood their assaults until they had succeeded in subjugating temporarily the

forces which had hemmed them in on every side. When the work of construction was

completed, Mulla Husayn undertook the necessary preparations for the siege which

the fort was destined to sustain, and provided, despite the obstacles which stood

in his way, whatever seemed essential for the safety of its occupants.  The work had scarcely been completed when

Shaykh Abu-Turab arrived bearing the news of Baha'u'llah's arrival at the village

of Nazar Khan. He informed Mulla Husayn

The work had scarcely been completed when

Shaykh Abu-Turab arrived bearing the news of Baha'u'llah's arrival at the village

of Nazar Khan. He informed Mulla Husayn

Baha'u'llah, in the course of that visit,

inspected the fort and expressed His satisfaction with the work that had been

accomplished. In His conversation with Mulla Husayn, He explained in detail such

matters as were vital to the welfare and safety of his companions. `The one thing

this fort and company require,' He said, `is the presence of Quddus. His association

with this company would render it complete and perfect.' He instructed Mulla Husayn

to despatch Mulla Mihdiy-i-Khu'i with six people to Sari, and to demand Mirza

Muhammad-Taqi that he immediately deliver Quddus into their hands. `The fear of

God and the dread of His punishment,' He assured Mulla Husayn, `will prompt him

to surrender unhesitatingly his captive.'

Baha'u'llah, in the course of that visit,

inspected the fort and expressed His satisfaction with the work that had been

accomplished. In His conversation with Mulla Husayn, He explained in detail such

matters as were vital to the welfare and safety of his companions. `The one thing

this fort and company require,' He said, `is the presence of Quddus. His association

with this company would render it complete and perfect.' He instructed Mulla Husayn

to despatch Mulla Mihdiy-i-Khu'i with six people to Sari, and to demand Mirza

Muhammad-Taqi that he immediately deliver Quddus into their hands. `The fear of

God and the dread of His punishment,' He assured Mulla Husayn, `will prompt him

to surrender unhesitatingly his captive.'  "Ere He departed, Baha'u'llah enjoined them

to be patient and resigned to the will of the Almighty. `If it be His will,' He

added, `We shall once again visit you at this same spot, and shall lend you Our

assistance. You have been chosen of God to be the vanguard of His host and the

establishers of His Faith. His host verily will conquer. Whatever may befall,

victory is yours, a victory which is complete and certain.' With these words,

He committed those valiant companions to the care of God, and returned to the

village with Nazar Khan and Shaykh Abu-Turab. From thence He departed by way of

Nur to Tihran."

"Ere He departed, Baha'u'llah enjoined them

to be patient and resigned to the will of the Almighty. `If it be His will,' He

added, `We shall once again visit you at this same spot, and shall lend you Our

assistance. You have been chosen of God to be the vanguard of His host and the

establishers of His Faith. His host verily will conquer. Whatever may befall,

victory is yours, a victory which is complete and certain.' With these words,

He committed those valiant companions to the care of God, and returned to the

village with Nazar Khan and Shaykh Abu-Turab. From thence He departed by way of

Nur to Tihran."  Mulla Husayn set out immediately to carry

out the instructions he had received. Summoning Mulla Mihdi, he bade him proceed

together with six other companions to Sari and ask that the mujtahid liberate

his prisoner. As soon as the message was conveyed to him, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi

Mulla Husayn set out immediately to carry

out the instructions he had received. Summoning Mulla Mihdi, he bade him proceed

together with six other companions to Sari and ask that the mujtahid liberate

his prisoner. As soon as the message was conveyed to him, Mirza Muhammad-Taqi

While in Sari, Quddus frequently

attempted to convince Mirza Muhammad-Taqi of the truth of the Divine Message.

He freely conversed with him on the most weighty and outstanding issues related

to the Revelation of the Bab. His bold and challenging remarks were couched in

such gentle, such persuasive and courteous language, and delivered with such geniality

and humour, that those who heard him felt not in the least offended. They even

misconstrued his allusions to the sacred Book as humorous observations intended

to entertain his hearers. Mirza Muhammad-Taqi, despite the cruelty and wickedness

that were latent in him and which he subsequently manifested by the stand he took

in insisting upon the extermination of the remnants of the defenders of the fort

of Shaykh Tabarsi, was withheld by an inner power from showing the least disrespect

to Quddus while the latter was confined in his home. He even was prompted to prevent

While in Sari, Quddus frequently

attempted to convince Mirza Muhammad-Taqi of the truth of the Divine Message.

He freely conversed with him on the most weighty and outstanding issues related

to the Revelation of the Bab. His bold and challenging remarks were couched in

such gentle, such persuasive and courteous language, and delivered with such geniality

and humour, that those who heard him felt not in the least offended. They even

misconstrued his allusions to the sacred Book as humorous observations intended

to entertain his hearers. Mirza Muhammad-Taqi, despite the cruelty and wickedness

that were latent in him and which he subsequently manifested by the stand he took

in insisting upon the extermination of the remnants of the defenders of the fort

of Shaykh Tabarsi, was withheld by an inner power from showing the least disrespect

to Quddus while the latter was confined in his home. He even was prompted to prevent

The news of the impending

arrival of Quddus bestirred the occupants of the fort of Tabarsi. As he drew near

his destination, he sent forward a messenger to announce his approach. The joyful

tidings gave them new courage and strength. Roused to a burst of enthusiasm which

he could not repress, Mulla Husayn started to his feet and, escorted by about

a hundred of his companions, hastened to meet the expected visitor. He placed

two candles in the hands of each, lighted them himself, and bade them proceed

to meet Quddus. The darkness of the night was dispelled by the radiance which

those joyous hearts shed as they marched forth to meet their beloved. In the midst

of the forest of Mazindaran, their eyes instantly recognised the face which they

had longed to behold. They pressed eagerly around his steed, and with every mark

of devotion aid him their tribute of love and undying allegiance. Still holding

the lighted candles in their hands, they followed him on foot towards their destination.

Quddus, as he rode along in their midst, appeared as the day-star that shines

amidst its satellites. As the company slowly wended its way towards the fort,

there broke forth the hymn of glorification and praise intoned by the band of

his enthusiastic admirers. "Holy, holy, the Lord our God, the Lord of the angels

and the spirit!" rang their jubilant voices around him. Mulla Husayn raised the

glad refrain, to which the entire company responded. The forest of Mazindaran

re-echoed to the sound of their acclamations.

The news of the impending

arrival of Quddus bestirred the occupants of the fort of Tabarsi. As he drew near

his destination, he sent forward a messenger to announce his approach. The joyful

tidings gave them new courage and strength. Roused to a burst of enthusiasm which

he could not repress, Mulla Husayn started to his feet and, escorted by about

a hundred of his companions, hastened to meet the expected visitor. He placed

two candles in the hands of each, lighted them himself, and bade them proceed

to meet Quddus. The darkness of the night was dispelled by the radiance which

those joyous hearts shed as they marched forth to meet their beloved. In the midst

of the forest of Mazindaran, their eyes instantly recognised the face which they

had longed to behold. They pressed eagerly around his steed, and with every mark

of devotion aid him their tribute of love and undying allegiance. Still holding

the lighted candles in their hands, they followed him on foot towards their destination.

Quddus, as he rode along in their midst, appeared as the day-star that shines

amidst its satellites. As the company slowly wended its way towards the fort,

there broke forth the hymn of glorification and praise intoned by the band of

his enthusiastic admirers. "Holy, holy, the Lord our God, the Lord of the angels

and the spirit!" rang their jubilant voices around him. Mulla Husayn raised the

glad refrain, to which the entire company responded. The forest of Mazindaran

re-echoed to the sound of their acclamations.  In this manner they reached the shrine of

Shaykh Tabarsi. The first words that fell from the lips of Quddus after he had

dismounted and leaned against the shrine were the following: "The Baqiyyatu'llah(1)

will be best for you if ye are of those who believe."(2)

By this utterance was fulfilled the prophecy of Muhammad as recorded in the following

tradition: "And when the Mihdi(3)

is made manifest, He shall lean His back against the Ka'bih and shall address

to the three hundred and thirteen followers who will have grouped around Him,

these words: `The Baqiyyatu'llah will be best for you if

In this manner they reached the shrine of

Shaykh Tabarsi. The first words that fell from the lips of Quddus after he had

dismounted and leaned against the shrine were the following: "The Baqiyyatu'llah(1)

will be best for you if ye are of those who believe."(2)

By this utterance was fulfilled the prophecy of Muhammad as recorded in the following

tradition: "And when the Mihdi(3)

is made manifest, He shall lean His back against the Ka'bih and shall address

to the three hundred and thirteen followers who will have grouped around Him,

these words: `The Baqiyyatu'llah will be best for you if

"Shortly after, Quddus entrusted to Mulla

Husayn a number of homilies which he asked him to read aloud to his assembled

companions. The first homily he read was entirely devoted to the Bab, the second

concerned Baha'u'llah, and the third referred to Tahirih. We ventured to express

to Mulla Husayn our doubts whether the references in the second homily were applicable

to Baha'u'llah, who appeared clothed in the garb of nobility. The matter was reported

to Quddus, who assured us that, God willing, its secret would be revealed to us

in due time. Utterly unaware, in those days, of the character of the Mission of

Baha'u'llah, we were unable to understand the meaning of those allusions, and

idly conjectured as to what could be their probable significance. In my eagerness

to unravel the subtleties of the traditions concerning the promised Qa'im, I several

times approached Quddus and requested him to enlighten me regarding that subject.

Though at first reluctant, he eventually acceded to my wish. The manner of his

answer, his convincing and illuminating explanations, served to heighten the sense

of awe and of veneration which his presence inspired. He dispelled whatever doubts

lingered in our minds, and such were the evidences of his perspicacity that we

came to believe that to him had been given the power to read our profoundest thoughts

and to calm the fiercest tumult in our hearts.

"Shortly after, Quddus entrusted to Mulla

Husayn a number of homilies which he asked him to read aloud to his assembled

companions. The first homily he read was entirely devoted to the Bab, the second

concerned Baha'u'llah, and the third referred to Tahirih. We ventured to express

to Mulla Husayn our doubts whether the references in the second homily were applicable

to Baha'u'llah, who appeared clothed in the garb of nobility. The matter was reported

to Quddus, who assured us that, God willing, its secret would be revealed to us

in due time. Utterly unaware, in those days, of the character of the Mission of

Baha'u'llah, we were unable to understand the meaning of those allusions, and

idly conjectured as to what could be their probable significance. In my eagerness

to unravel the subtleties of the traditions concerning the promised Qa'im, I several

times approached Quddus and requested him to enlighten me regarding that subject.

Though at first reluctant, he eventually acceded to my wish. The manner of his

answer, his convincing and illuminating explanations, served to heighten the sense

of awe and of veneration which his presence inspired. He dispelled whatever doubts

lingered in our minds, and such were the evidences of his perspicacity that we

came to believe that to him had been given the power to read our profoundest thoughts

and to calm the fiercest tumult in our hearts.  "Many a night I saw Mulla Husayn circle round

the shrine within the precincts of which Quddus lay asleep. How often did I see

him emerge in the mid-watches of the night from his chamber and quietly direct

his steps to that spot and whisper the same verse with which we all had greeted

"Many a night I saw Mulla Husayn circle round

the shrine within the precincts of which Quddus lay asleep. How often did I see

him emerge in the mid-watches of the night from his chamber and quietly direct

his steps to that spot and whisper the same verse with which we all had greeted

Quddus, on his arrival at the shrine of Shaykh

Tabarsi, charged Mulla Husayn to ascertain the number of the assembled companions.

One by one he counted them and passed them in through the gate of the fort: three

hundred and twelve in all. He himself was entering the fort in order to acquaint

Quddus with the result, when a youth, who had hastened all the way on foot from

Barfurush, suddenly rushed in and seizing the hem of his garment, pleaded to be

enrolled among the companions and to be allowed to lay down his life, whenever

required, in the path of the Beloved. His wish was readily granted. When Quddus

was informed of the total number of the companions, he remarked: "Whatever the

tongue of the Prophet of God has spoken concerning the promised One must needs

be fulfilled,(2) that thereby

His testimony may be complete in the eyes of those divines who esteem themselves

as the sole interpreters of the law and traditions of Islam. Through them will

the people recognise the truth and acknowledge the fulfilment of these traditions."(3)

Quddus, on his arrival at the shrine of Shaykh

Tabarsi, charged Mulla Husayn to ascertain the number of the assembled companions.

One by one he counted them and passed them in through the gate of the fort: three

hundred and twelve in all. He himself was entering the fort in order to acquaint

Quddus with the result, when a youth, who had hastened all the way on foot from

Barfurush, suddenly rushed in and seizing the hem of his garment, pleaded to be

enrolled among the companions and to be allowed to lay down his life, whenever

required, in the path of the Beloved. His wish was readily granted. When Quddus

was informed of the total number of the companions, he remarked: "Whatever the

tongue of the Prophet of God has spoken concerning the promised One must needs

be fulfilled,(2) that thereby

His testimony may be complete in the eyes of those divines who esteem themselves

as the sole interpreters of the law and traditions of Islam. Through them will

the people recognise the truth and acknowledge the fulfilment of these traditions."(3)

Every morning and every afternoon during those

days, Quddus would summon Mulla Husayn and the most distinguished among his companions

and ask them to chant the writings of the Bab. Seated in the Maydan, the open

square adjoining the fort, and surrounded by his devoted friends, he would listen

intently to the utterances of his Master and would occasionally be heard to comment

upon them. Neither the threats of the enemy nor the fierceness of their successive

onsets could induce him to abate the fervour, or to break the regularity, of his

devotions. Despising all danger and oblivious of his own needs and wants, he continued,

even under the most distressing circumstances, his daily communion with his Beloved,

wrote his praises of Him, and roused to fresh exertions the defenders of the fort.

Though exposed to the bullets that kept ceaselessly raining upon his besieged

companions, he, undeterred by the ferocity of the attack, pursued his labours

in a state of unruffled calm. "My soul is wedded to Thy mention!" he was wont

to exclaim. "Remembrance of Thee is the stay and solace of my life! I glory in

that I was the first to suffer ignominiously for Thy

Every morning and every afternoon during those

days, Quddus would summon Mulla Husayn and the most distinguished among his companions

and ask them to chant the writings of the Bab. Seated in the Maydan, the open

square adjoining the fort, and surrounded by his devoted friends, he would listen

intently to the utterances of his Master and would occasionally be heard to comment

upon them. Neither the threats of the enemy nor the fierceness of their successive

onsets could induce him to abate the fervour, or to break the regularity, of his

devotions. Despising all danger and oblivious of his own needs and wants, he continued,

even under the most distressing circumstances, his daily communion with his Beloved,

wrote his praises of Him, and roused to fresh exertions the defenders of the fort.

Though exposed to the bullets that kept ceaselessly raining upon his besieged

companions, he, undeterred by the ferocity of the attack, pursued his labours

in a state of unruffled calm. "My soul is wedded to Thy mention!" he was wont

to exclaim. "Remembrance of Thee is the stay and solace of my life! I glory in

that I was the first to suffer ignominiously for Thy

He would sometimes ask his Iraqi companions

to chant various passages of the Qur'an, to which he would listen with close attention,

and would often be moved to unfold their meaning. In the course of one of their

chantings, they came across the following verse: "With somewhat of fear and hunger,

and loss of wealth and lives and fruits, will We surely prove you: but bear good

tidings to the patient." "These words," Quddus would remark, "were originally

revealed with reference to Job and the afflictions that befell him. In this day,

however, they are applicable to us, who are destined to suffer those same afflictions.

Such will be the measure of our calamity that none but he who has been endowed

with constancy and patience will be able to survive them."

He would sometimes ask his Iraqi companions

to chant various passages of the Qur'an, to which he would listen with close attention,

and would often be moved to unfold their meaning. In the course of one of their

chantings, they came across the following verse: "With somewhat of fear and hunger,

and loss of wealth and lives and fruits, will We surely prove you: but bear good

tidings to the patient." "These words," Quddus would remark, "were originally

revealed with reference to Job and the afflictions that befell him. In this day,

however, they are applicable to us, who are destined to suffer those same afflictions.

Such will be the measure of our calamity that none but he who has been endowed

with constancy and patience will be able to survive them."  The knowledge and sagacity which Quddus displayed

on those occasions, the confidence with which he spoke, and the resource and enterprise

which he demonstrated in the instructions he gave to his companions, reinforced

his authority and enhanced his prestige. These at first supposed that the profound

The knowledge and sagacity which Quddus displayed

on those occasions, the confidence with which he spoke, and the resource and enterprise

which he demonstrated in the instructions he gave to his companions, reinforced

his authority and enhanced his prestige. These at first supposed that the profound

The completion of the fort, and the provision

of whatever was deemed essential for its defence, animated the enthusiasm of the

companions of Mulla Husayn and excited the curiosity of the people of the neighbourhood.(1)

A few out of sheer curiosity, others in pursuit of material interest, and still

others prompted by their devotion to the Cause which that building symbolised,

sought to be admitted within its walls and marvelled at the rapidity with which

it had been raised. Quddus had no sooner ascertained the number of its occupants

The completion of the fort, and the provision

of whatever was deemed essential for its defence, animated the enthusiasm of the

companions of Mulla Husayn and excited the curiosity of the people of the neighbourhood.(1)

A few out of sheer curiosity, others in pursuit of material interest, and still

others prompted by their devotion to the Cause which that building symbolised,

sought to be admitted within its walls and marvelled at the rapidity with which

it had been raised. Quddus had no sooner ascertained the number of its occupants

The providential manner in

which the occupants of the fort were relieved of the distress which weighed upon

them fanned to fury the wrath of the wilful and imperious Sa'idu'l-'Ulama'. Impelled

by an implacable hatred, he addressed a burning appeal to Nasiri'd-Din Shah, who

had recently ascended the throne, and expatiated upon the danger with which his

dynasty, nay the monarchy itself, was menaced. "The standard of revolt," he pleaded,

"has been raised by the contemptible sect of the Babis. This wretched band of

irresponsible agitators has dared to strike at the very foundations of the authority

with which your Imperial Majesty has been invested. The inhabitants of a number

of villages in the immediate vicinity of their headquarters have already flown

to their standard and sworn allegiance to their cause. They have built themselves

a fort, and in that massive stronghold they have entrenched themselves, ready

to direct a campaign against you. With unswerving obstinacy they

The providential manner in

which the occupants of the fort were relieved of the distress which weighed upon

them fanned to fury the wrath of the wilful and imperious Sa'idu'l-'Ulama'. Impelled

by an implacable hatred, he addressed a burning appeal to Nasiri'd-Din Shah, who

had recently ascended the throne, and expatiated upon the danger with which his

dynasty, nay the monarchy itself, was menaced. "The standard of revolt," he pleaded,

"has been raised by the contemptible sect of the Babis. This wretched band of

irresponsible agitators has dared to strike at the very foundations of the authority

with which your Imperial Majesty has been invested. The inhabitants of a number

of villages in the immediate vicinity of their headquarters have already flown

to their standard and sworn allegiance to their cause. They have built themselves

a fort, and in that massive stronghold they have entrenched themselves, ready

to direct a campaign against you. With unswerving obstinacy they

Nasiri'd-Din Shah, as yet inexperienced in

the affairs of State, referred the matter to the officers who commanded the army

of Mazindaran and who were in attendance upon him.(1)

He instructed them to take whatever means they deemed fit for the eradication

of the disturbers of his realm. Haji Mustafa Khan-i-Turkaman submitted his views

to his sovereign: "I myself come from Mazindaran. I have been able to estimate

the forces at their disposal. The handful of untrained and frail-bodied students

whom I have seen are utterly powerless to withstand the forces which your Majesty

can command. The army which you contemplate despatching is in my view unnecessary.

A small detachment of that army will be sufficient to wipe them out. They are

utterly unworthy of the care and consideration of my sovereign. Should your Majesty

be willing to signify your desire, in an imperial message addressed to my brother

Abdu'llah Khan-i-Turkaman,

Nasiri'd-Din Shah, as yet inexperienced in

the affairs of State, referred the matter to the officers who commanded the army

of Mazindaran and who were in attendance upon him.(1)

He instructed them to take whatever means they deemed fit for the eradication

of the disturbers of his realm. Haji Mustafa Khan-i-Turkaman submitted his views

to his sovereign: "I myself come from Mazindaran. I have been able to estimate

the forces at their disposal. The handful of untrained and frail-bodied students

whom I have seen are utterly powerless to withstand the forces which your Majesty

can command. The army which you contemplate despatching is in my view unnecessary.

A small detachment of that army will be sufficient to wipe them out. They are

utterly unworthy of the care and consideration of my sovereign. Should your Majesty

be willing to signify your desire, in an imperial message addressed to my brother

Abdu'llah Khan-i-Turkaman,

The Shah gave his consent, and issued his

farman(1) to that same

Abdu'llah Khan, bidding him to recruit without delay, from any part of his realm,

the forces he might require for the execution of his purpose. He sent with his

message a royal badge, which he bestowed upon him as a mark of confidence in his

capacity to undertake that task. The re-

The Shah gave his consent, and issued his

farman(1) to that same

Abdu'llah Khan, bidding him to recruit without delay, from any part of his realm,

the forces he might require for the execution of his purpose. He sent with his

message a royal badge, which he bestowed upon him as a mark of confidence in his

capacity to undertake that task. The re-

The army was ordered to set up a number of

barricades in front of the fort and to open fire upon anyone who chanced to leave

its gate. Quddus forbade his companions to go out in order to fetch water from

the neighbourhood. "Our bread has been intercepted by our enemy," complained Rasul-i-Bahnimiri.