430

CHAPTER XXI

THE SEVEN MARTYRS OF TIHRAN

HE news of the tragic fate which had befallen the heroes of Tabarsi

brought immeasurable sorrow to the heart of the Bab. Confined it His prison-castle

of Chihriq, severed from the little band of His struggling disciples, He watched

with keen anxiety the progress of their labours and prayed with unremitting zeal

for their victory. How great was His sorrow when, in the early days of Sha'ban

in the year 1265 A.H., (1) He

came to learn of the trials that had beset their path, of the agony they had suffered,

of the betrayal to which an exasperated enemy had felt compelled to resort, and

of the abominable butchery with which their career had ended.

HE news of the tragic fate which had befallen the heroes of Tabarsi

brought immeasurable sorrow to the heart of the Bab. Confined it His prison-castle

of Chihriq, severed from the little band of His struggling disciples, He watched

with keen anxiety the progress of their labours and prayed with unremitting zeal

for their victory. How great was His sorrow when, in the early days of Sha'ban

in the year 1265 A.H., (1) He

came to learn of the trials that had beset their path, of the agony they had suffered,

of the betrayal to which an exasperated enemy had felt compelled to resort, and

of the abominable butchery with which their career had ended.

"The Bab was heart-broken," His amanuensis,

Siyyid Husayn-i-'Aziz, subsequently related, "at the receipt of this unexpected

intelligence. He was crushed with grief, a grief that stilled His voice and silenced

His pen. For nine days He refused to meet any of His friends. I myself, though

His close and constant attendant, was refused admittance. Whatever meat or drink

we offered Him, He was disinclined to touch. Tears rained continually from His

eyes, and expressions of anguish dropped unceasingly from His lips. I could hear

Him, from behind the curtain, give vent to His feelings of sadness as He communed,

in the privacy of His cell, with His Beloved. I attempted to jot down the effusions

of His sorrow as they poured forth from His wounded heart. Suspecting that I was

attempting to preserve the lamentations He uttered, He bade me destroy whatever

I had recorded. Nothing remains of the moans and cries with which that heavy-laden

heart sought to relieve itself of the pangs that had seized it. For a period of

five months He languished, immersed in an ocean of despondency and sorrow."

"The Bab was heart-broken," His amanuensis,

Siyyid Husayn-i-'Aziz, subsequently related, "at the receipt of this unexpected

intelligence. He was crushed with grief, a grief that stilled His voice and silenced

His pen. For nine days He refused to meet any of His friends. I myself, though

His close and constant attendant, was refused admittance. Whatever meat or drink

we offered Him, He was disinclined to touch. Tears rained continually from His

eyes, and expressions of anguish dropped unceasingly from His lips. I could hear

Him, from behind the curtain, give vent to His feelings of sadness as He communed,

in the privacy of His cell, with His Beloved. I attempted to jot down the effusions

of His sorrow as they poured forth from His wounded heart. Suspecting that I was

attempting to preserve the lamentations He uttered, He bade me destroy whatever

I had recorded. Nothing remains of the moans and cries with which that heavy-laden

heart sought to relieve itself of the pangs that had seized it. For a period of

five months He languished, immersed in an ocean of despondency and sorrow."

431

With the advent of Muharram in the year 1266

A.H.,(1) the Bab again resumed

the work He had been compelled to interrupt. The first page He wrote was dedicated

to the memory of Mulla Husayn. In the visiting Tablet revealed in his honour,

He extolled, in moving terms, the unswerving fidelity with which he served Quddus

throughout the siege of the fort of Tabarsi. He lavished His eulogies on his magnanimous

conduct, recounted his exploits, and asserted his undoubted reunion in the world

beyond with the leader whom he had so nobly served. He too, He wrote, would soon

join those twin immortals, each of whom had, by his life and death, shed imperishable

lustre on the Faith of God. For one whole week the Bab continued to write His

praises of Quddus, of Mulla Husayn, and of His other companions who had gained

the crown of martyrdom at Tabarsi.

With the advent of Muharram in the year 1266

A.H.,(1) the Bab again resumed

the work He had been compelled to interrupt. The first page He wrote was dedicated

to the memory of Mulla Husayn. In the visiting Tablet revealed in his honour,

He extolled, in moving terms, the unswerving fidelity with which he served Quddus

throughout the siege of the fort of Tabarsi. He lavished His eulogies on his magnanimous

conduct, recounted his exploits, and asserted his undoubted reunion in the world

beyond with the leader whom he had so nobly served. He too, He wrote, would soon

join those twin immortals, each of whom had, by his life and death, shed imperishable

lustre on the Faith of God. For one whole week the Bab continued to write His

praises of Quddus, of Mulla Husayn, and of His other companions who had gained

the crown of martyrdom at Tabarsi.

No sooner had He completed His eulogies of

those who had immortalised their names in the defence of the fort, than He summoned,

on the day of Ashura, (2)Mulla

Adi-Guzal, (3) one of the believers

of Maraghih, who for the last two months had been acting as His attendant instead

of Siyyid Hasan, the brother of Siyyid Husayn-i-'Aziz. He affectionately received

him, bestowed upon him the name Sayyah, entrusted to his care the visiting Tablets

He had revealed in memory of the martyrs of Tabarsi, and bade him perform, on

His behalf, a pilgrimage to that spot. "Arise," He urged him, "and with complete

detachment proceed, in the guise of a traveller, to Mazindaran, and there visit,

on My behalf, the spot which enshrines the bodies of those immortals who, with

their blood, have sealed their faith in My Cause. As you approach the precincts

of that hallowed ground, put off your shoes and, bowing your head in reverence

to their memory, invoke their names and prayerfully make the circuit of their

shrine. Bring back to Me, as a remembrance of your visit, a handful of that holy

earth which covers the remains of My beloved ones, Quddus and Mulla

No sooner had He completed His eulogies of

those who had immortalised their names in the defence of the fort, than He summoned,

on the day of Ashura, (2)Mulla

Adi-Guzal, (3) one of the believers

of Maraghih, who for the last two months had been acting as His attendant instead

of Siyyid Hasan, the brother of Siyyid Husayn-i-'Aziz. He affectionately received

him, bestowed upon him the name Sayyah, entrusted to his care the visiting Tablets

He had revealed in memory of the martyrs of Tabarsi, and bade him perform, on

His behalf, a pilgrimage to that spot. "Arise," He urged him, "and with complete

detachment proceed, in the guise of a traveller, to Mazindaran, and there visit,

on My behalf, the spot which enshrines the bodies of those immortals who, with

their blood, have sealed their faith in My Cause. As you approach the precincts

of that hallowed ground, put off your shoes and, bowing your head in reverence

to their memory, invoke their names and prayerfully make the circuit of their

shrine. Bring back to Me, as a remembrance of your visit, a handful of that holy

earth which covers the remains of My beloved ones, Quddus and Mulla

432

Husayn. Strive to be back

ere the day of Naw-Ruz, that you may celebrate with Me that festival, the only

one I probably shall ever see again."

Faithful to the instructions

he had received, Sayyah set out on his pilgrimage to Mazindaran. He reached his

destination on the first day of Rabi'u'l-Avval in the year 1266 A.H.,(1)

and by the ninth day of that same month,(2)

the first anniversary of the martyrdom of Mulla Husayn, he had performed his visit

and acquitted himself of the mission with which he had been entrusted. From thence

he proceeded to Tihran.

Faithful to the instructions

he had received, Sayyah set out on his pilgrimage to Mazindaran. He reached his

destination on the first day of Rabi'u'l-Avval in the year 1266 A.H.,(1)

and by the ninth day of that same month,(2)

the first anniversary of the martyrdom of Mulla Husayn, he had performed his visit

and acquitted himself of the mission with which he had been entrusted. From thence

he proceeded to Tihran.

I have heard Aqay-i-Kalim, who received Sayyah

at the entrance of Baha'u'llah's home in Tihran, relate the following: "It was

the depth of winter when Sayyah, returning from his pilgrimage, came to visit

Baha'u'llah. Despite the cold and snow of a rigorous winter, he appeared attired

in the garb of a dervish, poorly clad, barefooted, and dishevelled. His heart

was set afire with the flame that pilgrimage had kindled. No sooner had Siyyid

Yahyay-i-Darabi, surnamed Vahid, who was then a guest in the home of Baha'u'llah,

been informed of the return of Sayyah from the fort of Tabarsi, than he, oblivious

of the pomp and circumstance to which a man of his position had been accustomed,

rushed forward and flung himself at the feet of the pilgrim. Holding his legs,

which had been covered with mud to the knees, in his arms, he kissed them devoutly.

I was amazed that day at the many evidences of loving solicitude which Baha'u'llah

evinced towards Vahid. He showed him such favours as I had never seen Him extend

to anyone. The manner of His conversation left no doubt in me that this same Vahid

would ere long distinguish himself by deeds no less remarkable than those which

had immortalised the defenders of the fort of Tabarsi."

I have heard Aqay-i-Kalim, who received Sayyah

at the entrance of Baha'u'llah's home in Tihran, relate the following: "It was

the depth of winter when Sayyah, returning from his pilgrimage, came to visit

Baha'u'llah. Despite the cold and snow of a rigorous winter, he appeared attired

in the garb of a dervish, poorly clad, barefooted, and dishevelled. His heart

was set afire with the flame that pilgrimage had kindled. No sooner had Siyyid

Yahyay-i-Darabi, surnamed Vahid, who was then a guest in the home of Baha'u'llah,

been informed of the return of Sayyah from the fort of Tabarsi, than he, oblivious

of the pomp and circumstance to which a man of his position had been accustomed,

rushed forward and flung himself at the feet of the pilgrim. Holding his legs,

which had been covered with mud to the knees, in his arms, he kissed them devoutly.

I was amazed that day at the many evidences of loving solicitude which Baha'u'llah

evinced towards Vahid. He showed him such favours as I had never seen Him extend

to anyone. The manner of His conversation left no doubt in me that this same Vahid

would ere long distinguish himself by deeds no less remarkable than those which

had immortalised the defenders of the fort of Tabarsi."

Sayyah tarried a few days in that home. He

was, however, unable to perceive, as did Vahid, the nature of that power which

lay latent in his Host. Though himself the recipient of the utmost favour from

Baha'u'llah, he failed to apprehend the significance of the blessings that were

being showered upon him. I have heard him recount his experiences, during his

sojourn in Famagusta: "Baha'u'llah overwhelmed

Sayyah tarried a few days in that home. He

was, however, unable to perceive, as did Vahid, the nature of that power which

lay latent in his Host. Though himself the recipient of the utmost favour from

Baha'u'llah, he failed to apprehend the significance of the blessings that were

being showered upon him. I have heard him recount his experiences, during his

sojourn in Famagusta: "Baha'u'llah overwhelmed

433

me with His kindness. As

to Vahid, notwithstanding the eminence of his position, he invariably gave me

preference over himself whenever in the presence of his Host. On the day of my

arrival from Mazindaran, he went so far as to kiss my feet. I was amazed at the

reception accorded me in that home. Though immersed in an ocean of bounty, I failed,

in those days, to appreciate the position then occupied by Baha'u'llah, nor was

I able to suspect, however dimly, the nature of the Mission He was destined to

perform."

Ere the departure of Sayyah

from Tihran, Baha'u'llah entrusted him with an epistle, the text of which He had

dictated to Mirza Yahya,(1)

and sent it in his name. Shortly after, a reply, penned in the Bab's own handwriting,

in which He commits Mirza Yahya to the care of Baha'u'llah and urges that attention

be paid to his education and training, was received. That communication the people

of the Bayan(2) have misconstrued

as an evidence of the exaggerated claims(3)

which they have advanced in favour of their leader. Although the text of that

reply is absolutely devoid of such pretensions, and does not, beyond the praise

it bestows upon Baha'u'llah and the request it makes for the upbringing of Mirza

Yahya, contain any reference to his alleged position, yet his followers have idly

imagined that that letter constitutes an assertion of the authority with which

they have invested him.(4)

Ere the departure of Sayyah

from Tihran, Baha'u'llah entrusted him with an epistle, the text of which He had

dictated to Mirza Yahya,(1)

and sent it in his name. Shortly after, a reply, penned in the Bab's own handwriting,

in which He commits Mirza Yahya to the care of Baha'u'llah and urges that attention

be paid to his education and training, was received. That communication the people

of the Bayan(2) have misconstrued

as an evidence of the exaggerated claims(3)

which they have advanced in favour of their leader. Although the text of that

reply is absolutely devoid of such pretensions, and does not, beyond the praise

it bestows upon Baha'u'llah and the request it makes for the upbringing of Mirza

Yahya, contain any reference to his alleged position, yet his followers have idly

imagined that that letter constitutes an assertion of the authority with which

they have invested him.(4)

At this stage of my narrative, when I have

already recounted the outstanding events that occurred in the course

At this stage of my narrative, when I have

already recounted the outstanding events that occurred in the course

434

of the year 1265 A.H., (1)

I am reminded that that very year witnessed the most significant event in my own

life, an event which marked my spiritual rebirth, my deliverance from the fetters

of the past, and my acceptance of the message of this Revelation. I seek the indulgence

of the reader if I dwell too long on the circumstances of my early life, and recount

with too great detail the events that led to my conversion. My father belonged

to the tribe of Tahiri, who led a nomadic life in the province of Khurasan. His

name was Ghulam Ali, son of Husayn-i-'Arab. He married the daughter of Kalb-'Ali,

and by her had three sons and three daughters. I was his second son, and was given

the name of Yar-Muhammad. I was born on the eighteenth of Safar in the year 1247

A.H.,(2) in the village of Zarand.

I was a shepherd by profession, and was given in my early days a most rudimentary

education. I longed to devote more time to my studies, but was unable to do so,

owing to the exigencies of my situation. I read the Qur'an with eagerness, committed

several of its passages to memory, and chanted them whilst I followed my flock

over the fields. I loved solitude, and watched the stars at night with delight

and wonder. In the quiet of the wilderness, I recited certain prayers attributed

to the Imam Ali, the Commander of the Faithful, and, as I turned my face towards

the Qiblih, (3) supplicated

the Almighty to guide my steps and enable me to find the Truth.

My father oftentimes took me with him to Qum,

where I became acquainted with the teachings of Islam and the ways and manners

of its leaders. He was a devout follower of that Faith, and was closely associated

with the ecclesiastical leaders who congregated in that city. I watched him as

he prayed at the Masjid-i-Imam-Hasan and performed, with scrupulous care and extreme

piety, all the rites and ceremonies prescribed by his Faith. I heard the preaching

of several eminent mujtahids who had arrived from Najaf, attended their lectures,

and listened to their disputations. Gradually I came to perceive their insincerity

and to loathe the baseness of their character. Eager as I was to ascertain the

trustworthiness of the creeds and dogmas which they strove to impose upon me,

I could neither find the time nor obtain the

My father oftentimes took me with him to Qum,

where I became acquainted with the teachings of Islam and the ways and manners

of its leaders. He was a devout follower of that Faith, and was closely associated

with the ecclesiastical leaders who congregated in that city. I watched him as

he prayed at the Masjid-i-Imam-Hasan and performed, with scrupulous care and extreme

piety, all the rites and ceremonies prescribed by his Faith. I heard the preaching

of several eminent mujtahids who had arrived from Najaf, attended their lectures,

and listened to their disputations. Gradually I came to perceive their insincerity

and to loathe the baseness of their character. Eager as I was to ascertain the

trustworthiness of the creeds and dogmas which they strove to impose upon me,

I could neither find the time nor obtain the

435

facilities with which to

satisfy my desire. I was often rebuked by my father for my temerity and restlessness.

"I fear," he often remarked, "that your aversion to these mujtahids may some day

involve you in great difficulties and bring upon you reproach and shame."

I was in the village of Rubat-Karim, on a

visit to my maternal uncle, when, on the twelfth day after Naw-Ruz, in the year

1263 A.H.,(1) I accidentally overheard, in

the masjid of that village, a conversation between two men which first made me

acquainted with the Revelation of the Bab. "Have you heard," one of them remarked,

"that the Siyyid-i-Bab has been conducted to the village of Kinar-Gird and is

on his way to Tihran?" Finding his friend ignorant of that episode, he proceeded

to relate the whole story of the Bab, giving a detailed account of the circumstances

attending His Declaration, of His arrest in Shiraz, His departure for Isfahan,

the reception which both the Imam-Jum'ih and Manuchihr Khan had extended to Him,

the prodigies and wonders He had manifested, and the verdict that the ulamas of

Isfahan had pronounced against Him. Every detail of that story excited my curiosity

and stirred in me a keen admiration for a Man who could throw such a spell over

His countrymen. His light seemed to have flooded my soul; I felt as if I were

already a convert to His Cause.

I was in the village of Rubat-Karim, on a

visit to my maternal uncle, when, on the twelfth day after Naw-Ruz, in the year

1263 A.H.,(1) I accidentally overheard, in

the masjid of that village, a conversation between two men which first made me

acquainted with the Revelation of the Bab. "Have you heard," one of them remarked,

"that the Siyyid-i-Bab has been conducted to the village of Kinar-Gird and is

on his way to Tihran?" Finding his friend ignorant of that episode, he proceeded

to relate the whole story of the Bab, giving a detailed account of the circumstances

attending His Declaration, of His arrest in Shiraz, His departure for Isfahan,

the reception which both the Imam-Jum'ih and Manuchihr Khan had extended to Him,

the prodigies and wonders He had manifested, and the verdict that the ulamas of

Isfahan had pronounced against Him. Every detail of that story excited my curiosity

and stirred in me a keen admiration for a Man who could throw such a spell over

His countrymen. His light seemed to have flooded my soul; I felt as if I were

already a convert to His Cause.

From Rubat-Karim I returned to Zarand. My

father remarked Upon my restlessness, and expressed his surprise at my behaviour.

I had lost my appetite and sleep, and was determined to conceal the secret of

my inner agitation from my father, lest its disclosure might interfere with the

eventual realisation of my hopes. I remained in that state until a certain Siyyid

Husayn-i-Zavari'i arrived at Zarand and was able to enlighten me on a subject

which had become the ruling passion of my life. Our acquaintance speedily ripened

into a friendship which encouraged me to share with him the longings of my heart.

To my great surprise, I found him already enthralled by the secret of the theme

which I had begun to disclose to him. "One of my cousins," he proceeded to relate,

"Siyyid Isma'il-i-Zavari'i by name, convinced me of the truth of the Message proclaimed

by the Siyyid-i-Bab.

From Rubat-Karim I returned to Zarand. My

father remarked Upon my restlessness, and expressed his surprise at my behaviour.

I had lost my appetite and sleep, and was determined to conceal the secret of

my inner agitation from my father, lest its disclosure might interfere with the

eventual realisation of my hopes. I remained in that state until a certain Siyyid

Husayn-i-Zavari'i arrived at Zarand and was able to enlighten me on a subject

which had become the ruling passion of my life. Our acquaintance speedily ripened

into a friendship which encouraged me to share with him the longings of my heart.

To my great surprise, I found him already enthralled by the secret of the theme

which I had begun to disclose to him. "One of my cousins," he proceeded to relate,

"Siyyid Isma'il-i-Zavari'i by name, convinced me of the truth of the Message proclaimed

by the Siyyid-i-Bab.

436

He informed me that he had

several times met the Siyyid-i-Bab in the house of the Imam-Jum'ih of Isfahan,

and had seen Him actually reveal, in the presence of His host, a commentary on

the Surih of Va'l-'Asr. (1)

The rapidity of the Bab's composition, and the force and originality of His style,

had excited his surprise and admiration. He was amazed to find that, whilst revealing

His commentary, and without lessening the speed of His writing, He was able to

answer whatever questions those who were present were moved to ask Him. The fearlessness

with which my cousin arose to preach the Message aroused the hostility of the

kad-khudas(2) and

siyyids of Zavarih, who compelled him to return to Isfahan, where he had of late

been residing. I too, unable to remain in Zavarih, departed for Kashan, in which

town I spent the winter and met Haji Mirza Jani, of whom my cousin had spoken,

and who gave me a treatise written by the Bab, entitled `Risaliy-i-'Adliyyih,'

urging me to read it carefully and return it to him after a few days. I was so

charmed by the theme and language of that treatise that I proceeded immediately

to transcribe the whole text. When I returned it to its owner, he, to my profound

regret, informed me that I had just missed the opportunity of meeting its Author.

`The Siyyid-i-Bab Himself,' he said, `arrived on the eve of the day of Naw-Ruz

and spent three nights as a Guest in my home. He is now on His way to Tihran,

and if you start immediately, you will certainly overtake Him.' Straightway I

arose and departed, walking all the way from Kashan to a fortress in the neighbourhood

of Kinar-Gird. I was resting under the shadow of its walls when a pleasant-looking

man emerged from that fortress and asked me who I was and whither I was going.

`I am a poor siyyid,' I replied, `a wayfarer and stranger to this place.' He took

me to his home and invited me to spend the night as his guest. In the course of

his conversation with me, he said: `I suspect you to be a follower of the Siyyid

who was staying for a few days in this fortress, from whence He was transferred

to the village of Kulayn, and who, three days ago, left for Adhirbayjan. I esteem

myself as one of His adherents. My name is Haji Zaynu'l-'Abidin. I intended not

to separate myself

437

from Him, but He bade me

remain in this place and convey to any of His friends whom I might meet His loving

greetings, and dissuade them from following Him. "Tell them," He instructed me,

"to consecrate their lives to the service of My Cause, that haply the barriers

that hinder the progress of this Faith may be removed, so that My followers may,

with safety and freedom, worship their God and observe the precepts of their Faith."

I immediately abandoned my project and, instead of returning to Qum, decided to

come to this place.'"

The story which this Siyyid Husayn-i- Zavari'i

related to me served to allay my agitation. He shared with me the copy of the

"Risaliy-i-'Adliyyih" he had brought with him, the reading of which imparted strength

and refreshment to my soul. In those days I was a pupil of a siyyid who taught

me the Qur'an and whose incapacity to enlighten me on the tenets of his Faith

became more and more evident in my eyes. Siyyid Husayn, whom I asked for further

information about the Cause, advised me to meet Siyyid Isma'il-i-Zavari'i, whose

invariable practice it was to visit, every spring, the shrines of the imam-zadihs(1)

of Qum. I induced my father, who was reluctant to separate himself from me, to

send me to that city with the object of perfecting my knowledge of the Arabic

language. I was careful to conceal from him my real purpose, fearing that its

disclosure might involve him in embarrassments with the Qadi(2)

and the ulamas of Zarand and prevent me from achieving my end.

The story which this Siyyid Husayn-i- Zavari'i

related to me served to allay my agitation. He shared with me the copy of the

"Risaliy-i-'Adliyyih" he had brought with him, the reading of which imparted strength

and refreshment to my soul. In those days I was a pupil of a siyyid who taught

me the Qur'an and whose incapacity to enlighten me on the tenets of his Faith

became more and more evident in my eyes. Siyyid Husayn, whom I asked for further

information about the Cause, advised me to meet Siyyid Isma'il-i-Zavari'i, whose

invariable practice it was to visit, every spring, the shrines of the imam-zadihs(1)

of Qum. I induced my father, who was reluctant to separate himself from me, to

send me to that city with the object of perfecting my knowledge of the Arabic

language. I was careful to conceal from him my real purpose, fearing that its

disclosure might involve him in embarrassments with the Qadi(2)

and the ulamas of Zarand and prevent me from achieving my end.

While I was in Qum, my mother, my sister,

and my brother came to visit me in connection with the festival of Naw-Ruz, and

stayed with me for about a month. In the course of their visit, I was able to

enlighten my mother and my sister about the new Revelation, and succeeded in kindling

in their hearts the love of its Author. A few days after their return to Zarand,

Siyyid Isma'il, whom I impatiently awaited, arrived, and was able, in the course

of his discussions with me, to set forth in detail all that was required to win

me over completely to the Cause. He laid stress on the continuity of Divine Revelation,

asserted the fundamental oneness of the Prophets of the past, and explained their

close relationship

While I was in Qum, my mother, my sister,

and my brother came to visit me in connection with the festival of Naw-Ruz, and

stayed with me for about a month. In the course of their visit, I was able to

enlighten my mother and my sister about the new Revelation, and succeeded in kindling

in their hearts the love of its Author. A few days after their return to Zarand,

Siyyid Isma'il, whom I impatiently awaited, arrived, and was able, in the course

of his discussions with me, to set forth in detail all that was required to win

me over completely to the Cause. He laid stress on the continuity of Divine Revelation,

asserted the fundamental oneness of the Prophets of the past, and explained their

close relationship

438

to the Mission of the Bab.

He also disclosed the nature of the work accomplished by Shaykh Ahmad-i-Ahsa'i

and Siyyid Kazim-i-Rashti, neither of whom I had previously heard. I asked as

to the duty incumbent at the present time upon every loyal adherent of the Faith.

"The injunction of the Bab," he replied, "is that all those have accepted His

Message should proceed to Mazindaran and their assistance to Quddus, who is now

hemmed in by the forces of an unrelenting foe." I expressed my eagerness to join

him,

439

as he himself was intending

to journey to the fort of Tabarsi. He advised me, however, to remain in Qum together

with a certain Mirza Fathu'llah-i-Hakkak, a lad of my age whom he had recently

guided to the Cause, until the receipt of his message from Tihran.

I waited in vain for that message, and, finding

that no word came from him, decided to leave for the capital. My friend Mirza

Fathu'llah subsequently followed me. He was eventually arrested and shared the

fate of those who were put to death in the year 1268 A.H. (1)

as a result of the attempt on the life or the Shah. Arriving in Tihran, I proceeded

directly to the Masjid-i-Shah, which was opposite a madrisih, (2)

at the entrance of which I, later on, unexpectedly encountered Siyyid Isma'il-i-Zavari'i,

who hastened to inform me that he had just written me the letter and was on the

point of despatching it to Qum.

I waited in vain for that message, and, finding

that no word came from him, decided to leave for the capital. My friend Mirza

Fathu'llah subsequently followed me. He was eventually arrested and shared the

fate of those who were put to death in the year 1268 A.H. (1)

as a result of the attempt on the life or the Shah. Arriving in Tihran, I proceeded

directly to the Masjid-i-Shah, which was opposite a madrisih, (2)

at the entrance of which I, later on, unexpectedly encountered Siyyid Isma'il-i-Zavari'i,

who hastened to inform me that he had just written me the letter and was on the

point of despatching it to Qum.

We were preparing ourselves to leave for Mazindaran,

when the news reached us that the defenders of the fort of Tabarsi had been treacherously

slaughtered and that the fort itself had been levelled with the ground. We were

filled with distress at the receipt of the appalling news, and mourned the tragic

fate of those who had so heroically defended their beloved Cause. One day I unexpectedly

came across my maternal uncle, Naw-Ruz-'Ali, who had come on purpose to fetch

me. I informed Siyyid Isma'il, who advised me to leave for Zarand and not to arouse

further hostility on the part of those who insisted upon my return.

We were preparing ourselves to leave for Mazindaran,

when the news reached us that the defenders of the fort of Tabarsi had been treacherously

slaughtered and that the fort itself had been levelled with the ground. We were

filled with distress at the receipt of the appalling news, and mourned the tragic

fate of those who had so heroically defended their beloved Cause. One day I unexpectedly

came across my maternal uncle, Naw-Ruz-'Ali, who had come on purpose to fetch

me. I informed Siyyid Isma'il, who advised me to leave for Zarand and not to arouse

further hostility on the part of those who insisted upon my return.

On my arrival at my native village, I was

able to win over my brother to the Cause, which my mother and my sister had already

embraced. I also succeeded in inducing my father to allow me to leave again for

Tihran. I took up my residence in the same madrisih where I had been accommodated

on my previous visit, and there met a certain Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, whom, I subsequently

learned, Baha'u'llah had named Mirza Ahmad. He affectionately received me and

told me that Siyyid Isma'il had entrusted me to his care and wished me to remain

in his company until the former's return to Tihran. The days of my companionship

with Mirza Ahmad will never be forgotten. I found him

On my arrival at my native village, I was

able to win over my brother to the Cause, which my mother and my sister had already

embraced. I also succeeded in inducing my father to allow me to leave again for

Tihran. I took up my residence in the same madrisih where I had been accommodated

on my previous visit, and there met a certain Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, whom, I subsequently

learned, Baha'u'llah had named Mirza Ahmad. He affectionately received me and

told me that Siyyid Isma'il had entrusted me to his care and wished me to remain

in his company until the former's return to Tihran. The days of my companionship

with Mirza Ahmad will never be forgotten. I found him

440

the very incarnation of love

and kindness. The words with which he inspired me and animated my faith are indelibly

graven upon my heart.

Through him I was introduced to the disciples

of the Bab, with whom I associated and from whom I obtained fuller information

regarding the teachings of the Faith. Mirza Ahmad was in those days earning his

livelihood as a scribe, and devoted his evenings to copying the Persian Bayan

and other writings of the Bab. The copies which he so devotedly prepared were

given by him as gifts to his fellow-disciples. I myself was several times the

bearer of such

Through him I was introduced to the disciples

of the Bab, with whom I associated and from whom I obtained fuller information

regarding the teachings of the Faith. Mirza Ahmad was in those days earning his

livelihood as a scribe, and devoted his evenings to copying the Persian Bayan

and other writings of the Bab. The copies which he so devotedly prepared were

given by him as gifts to his fellow-disciples. I myself was several times the

bearer of such

gifts from him to the wife

of Mulla Mihdiy-i-Kandi, who had forsaken his infant son and hastened to join

the occupants of the fort of Tabarsi.

gifts from him to the wife

of Mulla Mihdiy-i-Kandi, who had forsaken his infant son and hastened to join

the occupants of the fort of Tabarsi.

During those days I was informed that Tahirih,

who, ever since the dispersal of the gathering at Badasht, had been living in

Nur, had arrived at Tihran and was confined in the house of Mahmud Khan-i-Kalantar,

where, although a prisoner, she was treated with consideration and courtesy.

During those days I was informed that Tahirih,

who, ever since the dispersal of the gathering at Badasht, had been living in

Nur, had arrived at Tihran and was confined in the house of Mahmud Khan-i-Kalantar,

where, although a prisoner, she was treated with consideration and courtesy.

One day Mirza Ahmad conducted me to the house

of Baha'u'llah, whose wife, the Varaqatu'l-'Ulya, (1)

the mother of the Most Great Branch,(2)

had already healed my eyes with an ointment which she herself had prepared and

sent to me

One day Mirza Ahmad conducted me to the house

of Baha'u'llah, whose wife, the Varaqatu'l-'Ulya, (1)

the mother of the Most Great Branch,(2)

had already healed my eyes with an ointment which she herself had prepared and

sent to me

441

by this same Mirza Ahmad.

The first one I met in that house was that same beloved Son of hers, who was then

a child of six. He smiled His welcome to me as He was standing at the door of

the room which Baha'u'llah occupied. I passed that door, and was ushered into

the presence of Mirza Yahya, utterly unaware of the station of the Occupant of

the room I had left behind me. When brought face to face with Mirza Yahya, I was

startled, immediately I observed his features and noted his conversation, at his

utter unworthiness of the position that had been claimed for him.

On another occasion, when I visited that same

house, I on the point of entering the room that Mirza Yahya occupied, when Aqay-i-Kalim,

whom I had previously met, approached and requested me, since Isfandiyar, their

servant, had gone to market and had not yet returned, to conduct "Aqa"(1)

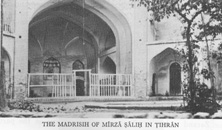

to the Madrisiy-i- Mirza-Salih in his stead and then return to this place. I gladly

consented, and as I was preparing to leave, I saw the Most Great Branch, a child

of exquisite beauty, wearing the kulah(2)

and cloaked in the jubbiy-i-hizari'i,(3)

emerge from the room which His Father occupied, and descend the steps leading

to the gate of the house. I advanced and stretched forth my arms to carry Him.

"We shall walk together," He said, as He took hold of my hand and led me out of

the house. We chatted together as we walked hand in hand in the direction of the

madrisih known in those days by the name of Pa-Minar. As we reached His classroom,

He turned to me and said: "Come again this afternoon and take me back to my home,

for Isfandiyar is unable to fetch me. My Father will need him to-day." I gladly

acquiesced, and returned immediately to the house of Baha'u'llah. There again

I met Mirza Yahya, who delivered into my hands a letter which he asked me to take

to the Madrisiy-i-Sadr and hand to Baha'u'llah, whom I was told I would find in

the room occupied by Mulla Baqir-i-Bastami. He asked me to bring back the reply

immediately. I fulfilled the commission and returned to the madrisih in time to

conduct the Most Great Branch to His home.

On another occasion, when I visited that same

house, I on the point of entering the room that Mirza Yahya occupied, when Aqay-i-Kalim,

whom I had previously met, approached and requested me, since Isfandiyar, their

servant, had gone to market and had not yet returned, to conduct "Aqa"(1)

to the Madrisiy-i- Mirza-Salih in his stead and then return to this place. I gladly

consented, and as I was preparing to leave, I saw the Most Great Branch, a child

of exquisite beauty, wearing the kulah(2)

and cloaked in the jubbiy-i-hizari'i,(3)

emerge from the room which His Father occupied, and descend the steps leading

to the gate of the house. I advanced and stretched forth my arms to carry Him.

"We shall walk together," He said, as He took hold of my hand and led me out of

the house. We chatted together as we walked hand in hand in the direction of the

madrisih known in those days by the name of Pa-Minar. As we reached His classroom,

He turned to me and said: "Come again this afternoon and take me back to my home,

for Isfandiyar is unable to fetch me. My Father will need him to-day." I gladly

acquiesced, and returned immediately to the house of Baha'u'llah. There again

I met Mirza Yahya, who delivered into my hands a letter which he asked me to take

to the Madrisiy-i-Sadr and hand to Baha'u'llah, whom I was told I would find in

the room occupied by Mulla Baqir-i-Bastami. He asked me to bring back the reply

immediately. I fulfilled the commission and returned to the madrisih in time to

conduct the Most Great Branch to His home.

One day Mirza Ahmad invited me to meet Haji

Mirza

One day Mirza Ahmad invited me to meet Haji

Mirza

442

Siyyid Ali, the Bab's maternal

uncle, who had recently returned from Chihriq and was staying in the home of Muhammad

Big-i-Chaparchi, in the neighbourhood of the gate of Shimiran. I was struck, when

I gazed at his face, with the nobility of his features and the serenity of his

countenance. My subsequent visits to him served to heighten my admiration for

the sweetness of his temper, his mystical piety and strength of character. I well

remember how on one occasion Aqay-i-Kalim urged him, at a certain gathering, to

leave Tihran, which was then in a state of great ferment, and escape its dangerous

atmosphere. "Why fear for my safety?"

he confidently replied. "Would

that I too could share in the banquet which the hand of Providence is spreading

for His chosen ones!"

he confidently replied. "Would

that I too could share in the banquet which the hand of Providence is spreading

for His chosen ones!"

Shortly after, the stirrers-up of mischief

were able to kindle a grave turmoil in that city. Its immediate cause was the

action of a certain siyyid from Kashan, who was living in the Madrisiy-i-Daru'sh-Shafa'

and whom the well-known Siyyid Muhammad had taken into his confidence and claimed

to have converted to the Bab's teachings. Mirza Muhammad-Husayn-i-Kirmani, who

lodged in that same madrisih and who was a well-known lecturer on the metaphysical

doctrines of Islam, attempted several times to induce Siyyid Muhammad,

Shortly after, the stirrers-up of mischief

were able to kindle a grave turmoil in that city. Its immediate cause was the

action of a certain siyyid from Kashan, who was living in the Madrisiy-i-Daru'sh-Shafa'

and whom the well-known Siyyid Muhammad had taken into his confidence and claimed

to have converted to the Bab's teachings. Mirza Muhammad-Husayn-i-Kirmani, who

lodged in that same madrisih and who was a well-known lecturer on the metaphysical

doctrines of Islam, attempted several times to induce Siyyid Muhammad,

443

who was one of his pupils,

to break off his acquaintance with that siyyid, whom he believed to be unreliable,

and to refuse him admittance to the gathering of the believers. Siyyid Muhammad

refused, however, to be admonished by this warning, and continued to associate

with him until the beginning of the month of Rabi'u'th-Thani in the year 1266

A.H.,(1) at which time the treacherous

siyyid went to a certain Siyyid Husayn, one of the ulamas of Kashan, and delivered

into his hands the names and addresses of about fifty of the

believers who were then residing

in Tihran. That same list was immediately submitted by Siyyid Husayn to Mahmud

Khan-i-Kalantar, who ordered that all of them be arrested. Fourteen of them were

seized and brought before the authorities.

believers who were then residing

in Tihran. That same list was immediately submitted by Siyyid Husayn to Mahmud

Khan-i-Kalantar, who ordered that all of them be arrested. Fourteen of them were

seized and brought before the authorities.

One the day they were captured, I happened

to be with my brother and my maternal uncle, who had arrived from Zarand and had

lodged in a caravanersai outside the gate of Naw. The next morning they departed

for Zarand, and

One the day they were captured, I happened

to be with my brother and my maternal uncle, who had arrived from Zarand and had

lodged in a caravanersai outside the gate of Naw. The next morning they departed

for Zarand, and

444

as I returned to the Madrisiy-i-Daru'sh-Shafa',

I discovered in my room a package upon which was placed a letter addressed to

me by Mirza Ahmad. That letter informed me that the treacherous siyyid had at

last denounced us and had raised a violent commotion in the capital. "The package

which I have left in this room," he wrote, "contains all the sacred writings that

are in my possession. If you ever reach this place in safety, take them to the

caravanserai of Haji Nad-'Ali, where you will find in one of its rooms a man bearing

that name, a native of Qazvin, to whom you will deliver the package together with

the letter which accompanies it. From thence you will proceed immediately to the

Masjid-i-Shah, where I hope to be able to meet you." Following his directions,

I delivered the package to the Haji and succeeded in reaching the masjid, where

I met Mirza Ahmad and heard him relate how he had been assailed and had sought

refuge in the masjid, in the precincts of which he was immune from further attack.

In the meantime, Baha'u'llah had sent from

the Madrisiyi-Sadr a message to Mirza Ahmad informing him of the designs of the

Amir-Nizam, who had, already on three different occasions, demanded his arrest

from the Imam-Jum'ih. He was also warned that the Amir, ignoring the right of

asylum with which the masjid had been invested, intended to arrest those who had

sought refuge in that sanctuary. Mirza Ahmad was urged to leave in disguise for

Qum, and was charged to direct me to return to my home in Zarand.

In the meantime, Baha'u'llah had sent from

the Madrisiyi-Sadr a message to Mirza Ahmad informing him of the designs of the

Amir-Nizam, who had, already on three different occasions, demanded his arrest

from the Imam-Jum'ih. He was also warned that the Amir, ignoring the right of

asylum with which the masjid had been invested, intended to arrest those who had

sought refuge in that sanctuary. Mirza Ahmad was urged to leave in disguise for

Qum, and was charged to direct me to return to my home in Zarand.

Meanwhile, my relations, who had recognised

me in the Masjid-i-Shah, pressed me to leave for Zarand, pleading that my father,

who had been misinformed of my arrest and impending execution, was in grave distress,

and that it was my duty to hasten and relieve him of his anxieties. Acting on

the advice of Mirza Ahmad, who counselled me to seize this God-sent opportunity,

I left for Zarand and celebrate the Feast of Naw-Ruz with my family, a Feast that

was doubly blessed inasmuch as it coincided with the fifth day of Jamadiyu'l-Avval

in the year 1266 A.H.,(1) the

anniversary of the day on which the Bab had declared His Mission. The Naw-Ruz

of that year has been mentioned in the "Kitab-i-Panj-Sha'n,"

Meanwhile, my relations, who had recognised

me in the Masjid-i-Shah, pressed me to leave for Zarand, pleading that my father,

who had been misinformed of my arrest and impending execution, was in grave distress,

and that it was my duty to hasten and relieve him of his anxieties. Acting on

the advice of Mirza Ahmad, who counselled me to seize this God-sent opportunity,

I left for Zarand and celebrate the Feast of Naw-Ruz with my family, a Feast that

was doubly blessed inasmuch as it coincided with the fifth day of Jamadiyu'l-Avval

in the year 1266 A.H.,(1) the

anniversary of the day on which the Bab had declared His Mission. The Naw-Ruz

of that year has been mentioned in the "Kitab-i-Panj-Sha'n,"

445

one of the last works of

the Bab. "The sixth Naw-Ruz," He wrote in that Book, "after the Declaration of

the Point of the Bayan,(1) has

fallen on the fifth day of Jamadiyu'l-Avval, in the seventh lunar year after that

same Declaration." In that same passage, the Bab alludes to the fact that the

Naw-Ruz of that year would be the last He was destined to celebrate on this earth.

In the midst of the festivities which my relatives

celebrated in Zarand, my heart was set upon Tihran, and my thoughts centred round

the fate which might have befallen my fellow-disciples in that agitated city.

I longed to hear of their safety. Though in the house of my father, and surrounded

with the solicitude of my parents, I felt oppressed by the thought of being severed

from that little band, whose perils I could well imagine and whose afflictions

I longed to share. The terrible suspense under which I lived, while confined in

my home, was unexpectedly relieved by the arrival of Sadiq-i-Tabrizi, who came

from Tihran and was received in the house of my father. Though delivering me from

the uncertainties which had been weighing so heavily upon me, he, to my profound

horror, unfolded to my ears a tale of such terrifying cruelty that the anxieties

of suspense paled before the ghastly light which that lurid story cast upon my

heart.

In the midst of the festivities which my relatives

celebrated in Zarand, my heart was set upon Tihran, and my thoughts centred round

the fate which might have befallen my fellow-disciples in that agitated city.

I longed to hear of their safety. Though in the house of my father, and surrounded

with the solicitude of my parents, I felt oppressed by the thought of being severed

from that little band, whose perils I could well imagine and whose afflictions

I longed to share. The terrible suspense under which I lived, while confined in

my home, was unexpectedly relieved by the arrival of Sadiq-i-Tabrizi, who came

from Tihran and was received in the house of my father. Though delivering me from

the uncertainties which had been weighing so heavily upon me, he, to my profound

horror, unfolded to my ears a tale of such terrifying cruelty that the anxieties

of suspense paled before the ghastly light which that lurid story cast upon my

heart.

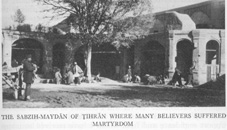

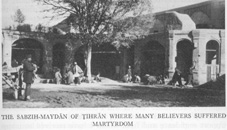

The circumstances of the martyrdom of my arrested

brethren in Tihran--for such was their fate--I now proceed to relate. The fourteen

disciples of the Bab, who had been captured, remained incarcerated in the house

of Mahmud Khan-i-Kalantar from the first to the twenty-second day of the month

of Rabi'u'th-Thani. (2) Tahirih

was also confined on the upper floor of that same house. Every kind of ill treatment

was inflicted upon them. Their persecutors sought, by every device, to induce

them to supply the information they required, but failed to obtain a satisfactory

answer. Among the captives was a certain Muhammad-Husayn-i-Maraghiyi, who obstinately

refused to utter a single word despite the severe pressure that was brought to

bear upon him. They tortured him, they resorted to every possible measure in order

to extort from him any hint that could

The circumstances of the martyrdom of my arrested

brethren in Tihran--for such was their fate--I now proceed to relate. The fourteen

disciples of the Bab, who had been captured, remained incarcerated in the house

of Mahmud Khan-i-Kalantar from the first to the twenty-second day of the month

of Rabi'u'th-Thani. (2) Tahirih

was also confined on the upper floor of that same house. Every kind of ill treatment

was inflicted upon them. Their persecutors sought, by every device, to induce

them to supply the information they required, but failed to obtain a satisfactory

answer. Among the captives was a certain Muhammad-Husayn-i-Maraghiyi, who obstinately

refused to utter a single word despite the severe pressure that was brought to

bear upon him. They tortured him, they resorted to every possible measure in order

to extort from him any hint that could

446

serve their purpose, but

failed to achieve their end. Such was his unswerving obstinacy that his oppressors

thought him to be dumb. They asked Haji Mulla Isma'il, who had converted him to

his Faith, whether or not he could talk. "He is mute, but not dumb," he replied;

"he is fluent of speech and is free from any impediment." He had no sooner called

him by his name than the victim answered, assuring him of his readiness to abide

by his will.

Convinced of their powerlessness to bend their

will, they referred the matter to Mahmud Khan, who, in his turn, submitted their

case to the Amir-Nizam, Mirza Taqi Khan, (1)

the Grand Vazir of Nasiri'd-Din Shah. The sovereign in those days refrained from

direct interference in matters pertaining to the affairs of the persecuted community,

and was often ignorant of the decisions that were being made with regard to its

members. His Grand Vazir was invested with plenary powers to deal with them as

he saw fit. No one questioned his decisions, nor dared disapprove of the manner

in which he exercised his authority. He immediately issued a peremptory order

threatening with execution whoever among these fourteen prisoners was unwilling

to recant his faith. Seven were compelled to yield to the pressure that was brought

to bear upon them, and were immediately released. The remaining seven constitute

the Seven Martyrs of Tihran:

Convinced of their powerlessness to bend their

will, they referred the matter to Mahmud Khan, who, in his turn, submitted their

case to the Amir-Nizam, Mirza Taqi Khan, (1)

the Grand Vazir of Nasiri'd-Din Shah. The sovereign in those days refrained from

direct interference in matters pertaining to the affairs of the persecuted community,

and was often ignorant of the decisions that were being made with regard to its

members. His Grand Vazir was invested with plenary powers to deal with them as

he saw fit. No one questioned his decisions, nor dared disapprove of the manner

in which he exercised his authority. He immediately issued a peremptory order

threatening with execution whoever among these fourteen prisoners was unwilling

to recant his faith. Seven were compelled to yield to the pressure that was brought

to bear upon them, and were immediately released. The remaining seven constitute

the Seven Martyrs of Tihran:

1. Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, surnamed Khal-i-A'zam,(2)

the Bab's maternal uncle, and one of the leading merchants of Shiraz. It was this

same uncle into whose custody the Bab, after the death of His father, was entrusted,

and who, on his Nephew's return from His pilgrimage to Hijaz and His arrest by

Husayn Khan, assumed undivided responsibility for Him by pledging his word in

writing. It was he who surrounded Him, while under his care, with unfailing solicitude,

who served Him with such devotion, and who acted as intermediary between Him and

the hosts of His followers who flocked to Shiraz to see Him. His only child, a

Siyyid Javad, died in infancy. Towards the middle of the year 1265 A.H.,(3)

1. Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, surnamed Khal-i-A'zam,(2)

the Bab's maternal uncle, and one of the leading merchants of Shiraz. It was this

same uncle into whose custody the Bab, after the death of His father, was entrusted,

and who, on his Nephew's return from His pilgrimage to Hijaz and His arrest by

Husayn Khan, assumed undivided responsibility for Him by pledging his word in

writing. It was he who surrounded Him, while under his care, with unfailing solicitude,

who served Him with such devotion, and who acted as intermediary between Him and

the hosts of His followers who flocked to Shiraz to see Him. His only child, a

Siyyid Javad, died in infancy. Towards the middle of the year 1265 A.H.,(3)

447

this same Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali left Shiraz and visited the Bab in the castle of Chihriq. From thence he went

to Tihran and, though having no special occupation, remained in that city until

the outbreak of the sedition which brought about eventually his martyrdom.

Though his friends appealed to him to escape

the turmoil that was fast approaching, he refused to heed their counsel and faced,

until his last hour, with complete resignation, the persecution to which he was

subjected. A considerable number among the more affluent merchants of his acquaintance

offered to pay his ransom, an offer which he rejected. Finally he was brought

before the Amir-Nizam. "The Chief Magistrate of this realm," the Grand Vazir informed

him, "is loth to inflict the slightest injury upon the Prophet's descendants.

Eminent merchants of Shiraz and Tihran are willing, nay eager, to pay your ransom.

The Maliku't-Tujjar has even interceded in your behalf. A word of recantation

from you is sufficient to set you free and ensure your return, with honours, to

your native city. I pledge my word that, should you be willing to acquiesce, the

remaining days of your life will be spent with honour and dignity under the sheltering

shadow of your sovereign." "Your Excellency," boldly replied Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali, "if others before me, who quaffed joyously the cup of martyrdom, have chosen

to reject an appeal such as the one you now make to me, know of a certainty that

I am no less eager to decline such a request. My repudiation of the truths enshrined

in this Revelation would be tantamount to a rejection of all the Revelations that

have preceded it. To refuse to acknowledge the Mission of the Siyyid-i-Bab would

be to apostatise from the Faith of my forefathers and to deny the Divine character

of the Message which Muhammad, Jesus, Moses, and all the Prophets of the past

have revealed. God knows that whatever I have heard and read concerning the sayings

and doings of those Messengers, I have been privileged to witness the same from

this Youth, this beloved Kinsman of mine, from His earliest boyhood to this, the

thirtieth year of His life. Everything in Him reminds me of His illustrious Ancestor

and of the imams of His Faith whose lives our recorded traditions have portrayed.

I only request of you that you allow me to be

Though his friends appealed to him to escape

the turmoil that was fast approaching, he refused to heed their counsel and faced,

until his last hour, with complete resignation, the persecution to which he was

subjected. A considerable number among the more affluent merchants of his acquaintance

offered to pay his ransom, an offer which he rejected. Finally he was brought

before the Amir-Nizam. "The Chief Magistrate of this realm," the Grand Vazir informed

him, "is loth to inflict the slightest injury upon the Prophet's descendants.

Eminent merchants of Shiraz and Tihran are willing, nay eager, to pay your ransom.

The Maliku't-Tujjar has even interceded in your behalf. A word of recantation

from you is sufficient to set you free and ensure your return, with honours, to

your native city. I pledge my word that, should you be willing to acquiesce, the

remaining days of your life will be spent with honour and dignity under the sheltering

shadow of your sovereign." "Your Excellency," boldly replied Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali, "if others before me, who quaffed joyously the cup of martyrdom, have chosen

to reject an appeal such as the one you now make to me, know of a certainty that

I am no less eager to decline such a request. My repudiation of the truths enshrined

in this Revelation would be tantamount to a rejection of all the Revelations that

have preceded it. To refuse to acknowledge the Mission of the Siyyid-i-Bab would

be to apostatise from the Faith of my forefathers and to deny the Divine character

of the Message which Muhammad, Jesus, Moses, and all the Prophets of the past

have revealed. God knows that whatever I have heard and read concerning the sayings

and doings of those Messengers, I have been privileged to witness the same from

this Youth, this beloved Kinsman of mine, from His earliest boyhood to this, the

thirtieth year of His life. Everything in Him reminds me of His illustrious Ancestor

and of the imams of His Faith whose lives our recorded traditions have portrayed.

I only request of you that you allow me to be

448

the first to lay down my

life in the path of my beloved Kinsman."

The Amir was stupefied by such an answer.

In a frenzy of despair, and without uttering a word, he motioned that he be taken

out and beheaded. As the victim was being conducted to his death, he was heard,

several times, to repeat these words of Hafiz: "Great is my gratitude to Thee,

O my God, for having granted so bountifully all I have asked of Thee." "Hear me,

O people," he cried to the multitude that pressed around him; "I have offered

myself up as a willing sacrifice in the path of the Cause of God. The entire province

of Fars, as well as Iraq, beyond the confines of Persia, will readily testify

to my uprightness of conduct, to my sincere piety and noble lineage. For over

a thousand years, you have prayed and prayed again that the promised Qa'im be

made manifest. At the mention of His name, how often have you cried, from the

depths of your hearts: `Hasten, O God, His coming; remove every barrier that stands

in the way of His appearance!' And now that He is come, you have driven Him to

a hopeless exile in a remote and sequestered corner of Adhirbayjan and have risen

to exterminate His companions. Were I to invoke the malediction of God upon you,

I am certain that His avenging wrath would grievously afflict you. Such is not,

however, my prayer. With my last breath, I pray that the Almighty may wipe away

the stain of your guilt and enable you to awaken from the sleep of heedlessness."(1)

The Amir was stupefied by such an answer.

In a frenzy of despair, and without uttering a word, he motioned that he be taken

out and beheaded. As the victim was being conducted to his death, he was heard,

several times, to repeat these words of Hafiz: "Great is my gratitude to Thee,

O my God, for having granted so bountifully all I have asked of Thee." "Hear me,

O people," he cried to the multitude that pressed around him; "I have offered

myself up as a willing sacrifice in the path of the Cause of God. The entire province

of Fars, as well as Iraq, beyond the confines of Persia, will readily testify

to my uprightness of conduct, to my sincere piety and noble lineage. For over

a thousand years, you have prayed and prayed again that the promised Qa'im be

made manifest. At the mention of His name, how often have you cried, from the

depths of your hearts: `Hasten, O God, His coming; remove every barrier that stands

in the way of His appearance!' And now that He is come, you have driven Him to

a hopeless exile in a remote and sequestered corner of Adhirbayjan and have risen

to exterminate His companions. Were I to invoke the malediction of God upon you,

I am certain that His avenging wrath would grievously afflict you. Such is not,

however, my prayer. With my last breath, I pray that the Almighty may wipe away

the stain of your guilt and enable you to awaken from the sleep of heedlessness."(1)

These words stirred his executioner to his

very depths. Pretending that the sword he had been holding in readiness in his

hands required to be resharpened, he hastily went away, determined never to return

again. "When I was appointed to this service," he was heard to complain, weeping

bitterly the while, "they undertook to deliver into my hands only those who had

been convicted of murder and highway robbery. I am now ordered by them to shed

the blood of

These words stirred his executioner to his

very depths. Pretending that the sword he had been holding in readiness in his

hands required to be resharpened, he hastily went away, determined never to return

again. "When I was appointed to this service," he was heard to complain, weeping

bitterly the while, "they undertook to deliver into my hands only those who had

been convicted of murder and highway robbery. I am now ordered by them to shed

the blood of

449

one no less holy than the

Imam Musay-i-Kazim (1) himself!"

Shortly after, he departed for Khurasan and there sought to earn his livelihood

as a porter and crier. To the believers of that province, he recounted the tale

of that tragedy, and expressed his repentance of the act which he had been compelled

to perpetrate. Every time he recalled that incident, every time the name of Haji

Mirza Siyyid Ali was mentioned to him, tears which he could not repress flowed

from his eyes, tears that were a witness to the affection which that holy man

had instilled into his heart.

2. Mirza Qurban-'Ali,(2) a native of Barfurush in the

province of Mazindaran, and an outstanding figure in the community known by the

name of Ni'matu'llahi. He was a man of sincere piety and endowed with great nobleness

of nature. Such was the purity of his life that a considerable number among the

notables of Mazindaran, of Khurasan and Tihran had pledged him their loyalty,

and regarded him as the very embodiment of virtue. Such was the esteem in which

he was held by his countrymen that, on the occasion of his pilgrimage to Karbila,

a vast concourse of devoted admirers thronged his route in order to pay their

homage to him. In Hamadan, as well as in Kirmanshah, a great number of people

were influenced by his personality and joined the company of his followers. Wherever

he went, he was greeted with the acclamations of the people. These demonstrations

of popular enthusiasm were, however, extremely distasteful to him. He avoided

the crowd and disdained the pomp and circumstance of leadership. On his way to

Karbila, while passing through Mandalij, a shaykh of considerable influence became

so enamoured of him that he renounced all that he had formerly cherished and,

leaving his friends and disciples, followed him as far as Ya'qubiyyih. Mirza Qurban-'Ali,

however, succeeded in inducing him to return to Mandalij and resume the work which

he had abandoned.

2. Mirza Qurban-'Ali,(2) a native of Barfurush in the

province of Mazindaran, and an outstanding figure in the community known by the

name of Ni'matu'llahi. He was a man of sincere piety and endowed with great nobleness

of nature. Such was the purity of his life that a considerable number among the

notables of Mazindaran, of Khurasan and Tihran had pledged him their loyalty,

and regarded him as the very embodiment of virtue. Such was the esteem in which

he was held by his countrymen that, on the occasion of his pilgrimage to Karbila,

a vast concourse of devoted admirers thronged his route in order to pay their

homage to him. In Hamadan, as well as in Kirmanshah, a great number of people

were influenced by his personality and joined the company of his followers. Wherever

he went, he was greeted with the acclamations of the people. These demonstrations

of popular enthusiasm were, however, extremely distasteful to him. He avoided

the crowd and disdained the pomp and circumstance of leadership. On his way to

Karbila, while passing through Mandalij, a shaykh of considerable influence became

so enamoured of him that he renounced all that he had formerly cherished and,

leaving his friends and disciples, followed him as far as Ya'qubiyyih. Mirza Qurban-'Ali,

however, succeeded in inducing him to return to Mandalij and resume the work which

he had abandoned.

On his return from his pilgrimage, Mirza Qurban-'Ali

met Mulla Husayn and through him embraced the truth of the Cause. Owing to illness,

he was unable to join the defenders

On his return from his pilgrimage, Mirza Qurban-'Ali

met Mulla Husayn and through him embraced the truth of the Cause. Owing to illness,

he was unable to join the defenders

450

of the fort of Tabarsi, and,

but for his unfitness to travel to Mazindaran, would have been the first to join

its occupants. Next to Mulla Husayn, among the disciples of the Bab, Vahid was

the person to whom he was most attached. During my visit to Tihran, I was informed

that the latter had consecrated his life to the service of the Cause and had risen

with exemplary devotion to promote its interests far and wide. I often heard Mirza

Qurban-'Ali, who was then in the capital, deplore that illness. "How greatly I

grieve," I heard him several times remark, "to have been deprived of my share

of the cup which Mulla Husayn and his companions have quaffed! I long to join

Vahid and enrol myself under his banner and strive to make amends for my previous

failure." He was preparing to leave Tihran, when he was suddenly arrested. His

modest attire witnessed to the degree of his detachment. Clad in a white tunic,

after the manner of the Arabs, cloaked in a coarsely woven aba,(1)

and wearing the head-dress of the people of Iraq, he seemed, as he walked the

streets, the very embodiment of renunciation. He scrupulously adhered to all the

observances of his Faith, and with exemplary piety performed his devotions. "The

Bab Himself conforms to the observances of His Faith in their minutest details,"

he often remarked. "Am I to neglect on my part the things which are observed by

my Leader?"

When Mirza Qurban-'Ali was arrested and brought

before the Amir-Nizam, a commotion such as Tihran had rarely experienced was raised.

Large crowds of people thronged the approaches to the headquarters of the government,

eager to learn what would befall him. "Since last night," the Amir, as soon as

he had seen him, remarked, "I have been besieged by all classes of State officials

who have vigorously interceded in your behalf.(2)

From what I learn of the position you occupy and the influence your words exercise,

you are not

When Mirza Qurban-'Ali was arrested and brought

before the Amir-Nizam, a commotion such as Tihran had rarely experienced was raised.

Large crowds of people thronged the approaches to the headquarters of the government,

eager to learn what would befall him. "Since last night," the Amir, as soon as

he had seen him, remarked, "I have been besieged by all classes of State officials

who have vigorously interceded in your behalf.(2)

From what I learn of the position you occupy and the influence your words exercise,

you are not

451

much inferior to the Siyyid-i-Bab

Himself. Had you claimed for yourself the position of leadership, better would

it have been than to declare your allegiance to one who is certainly inferior

to you in knowledge." "The knowledge which I have acquired," he boldly retorted,

"has led me to bow down in allegiance before Him whom I have recognised to be

my Lord and Leader. Ever since I attained the age of manhood, I have regarded

justice and fairness as the ruling motives of my life. I have judged Him fairly,

and have reached the conclusion that should this Youth, to whose transcendent

power friend and foe alike testify, be false, every Prophet of God, from time

immemorial down to the present day, should be denounced as the very embodiment

of falsehood! I am assured of the unquestioning devotion of over a thousand admirers,

and yet I am powerless to change the heart of the least among them. This Youth,

however, has proved Himself capable of transmuting, through the elixir of His

love, the souls of the most degraded among His fellow men. Upon a thousand like

me He has, unaided and alone, exerted such influence that, without even attaining

His presence, they have flung aside their own desires and have clung passionately

to His will. Fully conscious of the inadequacy of the sacrifice they have made,

these yearn to lay down their lives for His sake, in the hope that this further

evidence of their devotion may be worthy of mention in His Court."

"I am loth," the Amir-Nizam remarked, "whether

your words be of God or not, to pronounce the sentence of death against the possessor

of so exalted a station." "Why hesitate? burst forth the impatient victim. "Are

you not aware that all names descend from Heaven? He whose name is Ali,(1)

in whose path I am laying down my life, has

"I am loth," the Amir-Nizam remarked, "whether

your words be of God or not, to pronounce the sentence of death against the possessor

of so exalted a station." "Why hesitate? burst forth the impatient victim. "Are

you not aware that all names descend from Heaven? He whose name is Ali,(1)

in whose path I am laying down my life, has

452

from time immemorial inscribed

my name, Qurban-'Ali, (1) in

the scroll of His chosen martyrs. This is indeed the day on which I celebrate

the Qurban festival, the day on which I shall seal with my life-blood my faith

in His Cause. Be not, therefore, reluctant, and rest assured that I shall never

blame you for your act. The sooner you strike off my head, the greater will be

my gratitude to you." "Take him away from this place!" cried the Amir. "Another

moment, and this dervish will have cast his spell over me!" "You are proof against

that magic," Mirza Qurban-'Ali replied, "that can captivate only the pure in heart.

You and your like can never be made to realise the entrancing power of that Divine

elixir which, swift as the twinkling of an eye, transmutes the souls of men."

Exasperated by the reply, the Amir- Nizam

arose from his seat and, his whole frame shaking with anger, exclaimed: "Nothing

but the edge of the sword can silence the voice of this deluded people!" "No need,"

he told the executioners who were in attendance upon him, "to bring any more members

of this hateful sect before me. Words are powerless to overcome their unswerving

obstinacy. Whomever you are able to induce to recant his faith, release him; as

for the rest, strike off their heads."

Exasperated by the reply, the Amir- Nizam

arose from his seat and, his whole frame shaking with anger, exclaimed: "Nothing

but the edge of the sword can silence the voice of this deluded people!" "No need,"

he told the executioners who were in attendance upon him, "to bring any more members

of this hateful sect before me. Words are powerless to overcome their unswerving

obstinacy. Whomever you are able to induce to recant his faith, release him; as

for the rest, strike off their heads."

As he drew near the scene of his death, Mirza

Qurban-'Ali, intoxicated with the prospect of an approaching reunion with his

Beloved, broke forth into expressions of joyous exultation. "Hasten to slay me,"

he cried with rapturous delight, "for through this death you will have offered

me the chalice of everlasting life. Though my withered breath you now extinguish,

with a myriad lives will my Beloved reward me; lives such as no mortal heart can

conceive!" "Hearken to my words, you who profess to be the followers of the Apostle

of God," he pleaded, as he turned his gaze to the concourse of spectators. "Muhammad,

the Day-Star of Divine guidance, who in a former age arose above the horizon of

Hijaz, has to-day, in the person of Ali-Muhammad, again risen from the Day-Spring

of Shiraz, shedding the same radiance and imparting the same warmth. A rose is

a rose in whichever garden, and at whatever time, it may bloom." Seeing on

As he drew near the scene of his death, Mirza

Qurban-'Ali, intoxicated with the prospect of an approaching reunion with his

Beloved, broke forth into expressions of joyous exultation. "Hasten to slay me,"

he cried with rapturous delight, "for through this death you will have offered

me the chalice of everlasting life. Though my withered breath you now extinguish,

with a myriad lives will my Beloved reward me; lives such as no mortal heart can

conceive!" "Hearken to my words, you who profess to be the followers of the Apostle

of God," he pleaded, as he turned his gaze to the concourse of spectators. "Muhammad,

the Day-Star of Divine guidance, who in a former age arose above the horizon of

Hijaz, has to-day, in the person of Ali-Muhammad, again risen from the Day-Spring

of Shiraz, shedding the same radiance and imparting the same warmth. A rose is

a rose in whichever garden, and at whatever time, it may bloom." Seeing on

453

every side how the people

were deaf to his call, he cried aloud: "Oh, the perversity of this generation!

How heedless of the fragrance which that imperishable Rose has shed! Though my

soul brim over with ecstasy, I can, alas, find no heart to share with me itS charm,

nor mind to apprehend its glory."

At the sight of the body of Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali, beheaded and bleeding at his feet, his fevered excitement rose to its highest