595

CHAPTER XXVI

ATTEMPT ON THE SHAH'S LIFE, AND

ITS CONSEQUENCES

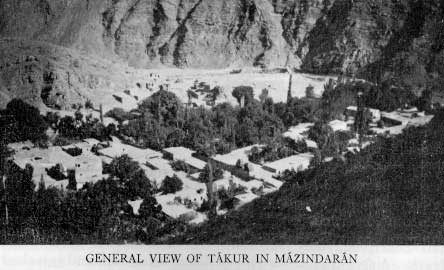

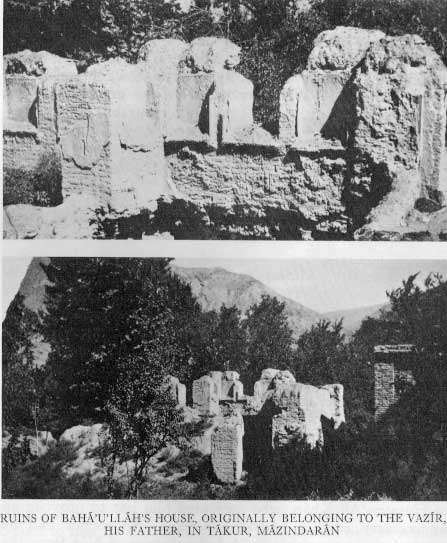

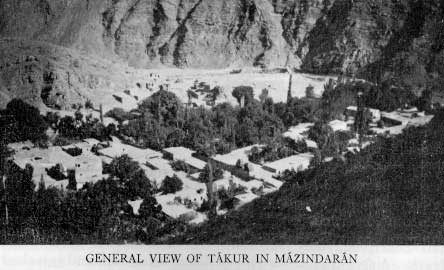

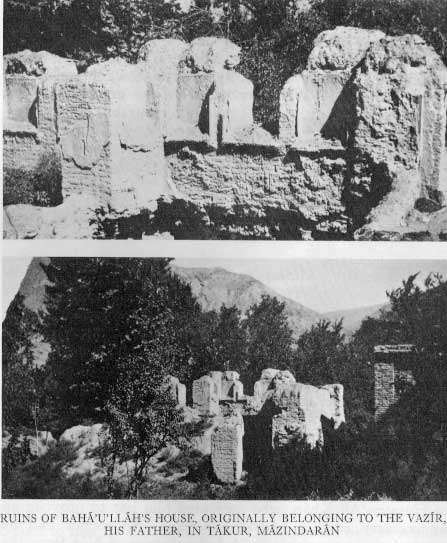

HE eighth Naw-Ruz after the Declaration of the Bab, which fell

on the twenty-seventh day of the month of Jamadiyu'l-Avval, in the year 1268 A.H.,(1)

found Baha'u'llah still in Iraq, engaged in spreading the teachings, and making

firm the foundations, of the New Revelation. Displaying an enthusiasm and ability

that recalled His activities in the early days of the Movement in Nur and Mazindaran,

He continued to devote Himself to the task of reviving the energies, of organising

the forces, and of directing the efforts, of the Bab's scattered companions. He

was the sole light amidst the darkness that encompassed the bewildered disciples

who had witnessed, on the one hand, the cruel martyrdom of their beloved Leader

and, on the other, the tragic fate of their companions. He alone was able to inspire

them with the needful courage and fortitude to endure the many afflictions that

had been heaped upon them; He alone was capable of preparing them for the burden

of the task they were destined to bear, and of inuring them to brave the storm

and perils they were soon to face.

HE eighth Naw-Ruz after the Declaration of the Bab, which fell

on the twenty-seventh day of the month of Jamadiyu'l-Avval, in the year 1268 A.H.,(1)

found Baha'u'llah still in Iraq, engaged in spreading the teachings, and making

firm the foundations, of the New Revelation. Displaying an enthusiasm and ability

that recalled His activities in the early days of the Movement in Nur and Mazindaran,

He continued to devote Himself to the task of reviving the energies, of organising

the forces, and of directing the efforts, of the Bab's scattered companions. He

was the sole light amidst the darkness that encompassed the bewildered disciples

who had witnessed, on the one hand, the cruel martyrdom of their beloved Leader

and, on the other, the tragic fate of their companions. He alone was able to inspire

them with the needful courage and fortitude to endure the many afflictions that

had been heaped upon them; He alone was capable of preparing them for the burden

of the task they were destined to bear, and of inuring them to brave the storm

and perils they were soon to face.

In the course of the spring

of that year, Mirza Taqi Khan, the Amir-Nizam, the Grand Vazir of Nasiri'd-Din

Shah, who had been guilty of such infamous outrages against the Bab an His companions,

met his death in a public bath in Fin, near Kashan,(2)

having miserably failed to stay the

In the course of the spring

of that year, Mirza Taqi Khan, the Amir-Nizam, the Grand Vazir of Nasiri'd-Din

Shah, who had been guilty of such infamous outrages against the Bab an His companions,

met his death in a public bath in Fin, near Kashan,(2)

having miserably failed to stay the

596

onrush of the Faith he had

striven so desperately to crush. His own fame and honour were destined eventually

to perish with his death, and not the influence of the life he had sought to extinguish.

During the three years when he held the post of Grand Vazir of Persia, his ministry

was stained with deeds of blackest infamy. What atrocities did not his hands commit

as they were stretched forth to tear down the fabric the Bab had raised! To what

treacherous measures did he not resort, in his impotent rage, in order to sap

the vitality of a Cause which he feared and hated! The first year of his administration

was marked by the ferocious onslaught of the imperial army of Nasiri'd-Din Shah

against the defenders of the fort of Tabarsi. With what ruthlessness he conducted

the campaign of repression against those innocent upholders of the Faith of God!

What fury and eloquence he displayed in pleading for the extermination of the

lives of Quddus, of Mulla Husayn, and of three hundred and thirteen of the best

and noblest of his countrymen! The second year of his ministry found him battling

with savage determination to extirpate the Faith in the capital. It was he who

authorised and encouraged the capture of the believers who resided in that city,

and who ordered the execution of the Seven Martyrs of Tihran. It was he who unchained

the offensive against Vahid and his companions, who inspired that campaign of

revenge which animated their persecutors, and who instigated them to commit the

abominations with which that episode will for ever remain associated. That same

year witnessed another blow more terrible than any he had hitherto dealt that

persecuted community, a blow that brought to a tragic end the life of Him who

was the Source of all the forces he had in vain sought to repress. The last years

of that Vazir's life will for ever remain associated with the most revolting of

the vast campaigns which his ingenious mind had devised,

597

598

a campaign that involved

the destruction of the lives of Hujjat and of no less than eighteen hundred of

his companions. Such were the distinguishing features of a career that began and

ended in a reign of terror such as Persia had seldom seen.

He was succeeded by Mirza

Aqa Khan-i-Nuri,(1) who endeavoured,

at the very outset of his ministry, to effect a reconciliation between the government

of which he was the head and Baha'u'llah, whom he regarded as the most capable

He was succeeded by Mirza

Aqa Khan-i-Nuri,(1) who endeavoured,

at the very outset of his ministry, to effect a reconciliation between the government

of which he was the head and Baha'u'llah, whom he regarded as the most capable

of the Bab's disciples. He

sent Him a warm letter requesting Him to return to Tihran, and expressing his

eagerness to meet Him. Ere the receipt of that letter, Baha'u'llah had already

decided to leave Iraq for Persia.

of the Bab's disciples. He

sent Him a warm letter requesting Him to return to Tihran, and expressing his

eagerness to meet Him. Ere the receipt of that letter, Baha'u'llah had already

decided to leave Iraq for Persia.

He arrived in the capital in the month of

Rajab,(2) and was welcomed by

the Grand Vazir's brother, Ja'far-Quli Khan, who had been specially directed to

go forth to receive Him. For one whole month, He was the honoured Guest of

He arrived in the capital in the month of

Rajab,(2) and was welcomed by

the Grand Vazir's brother, Ja'far-Quli Khan, who had been specially directed to

go forth to receive Him. For one whole month, He was the honoured Guest of

599

the Grand Vazir, who had

appointed his brother to act as host on his behalf. So great was the number of

the notables and dignitaries of the capital who flocked to meet Him that He found

Himself unable to return to His own home. He remained in that house until His

departure for Shimiran.(1)

I have heard it stated by

Aqay-i-Kalim that in the course of that journey Baha'u'llah was able to meet Azim,

who had been endeavouring for a long time to see Him, and who in that interview

was advised, in the most emphatic terms, to abandon the plan he had conceived.

Baha'u'llah condemned his designs, dissociated Himself entirely from the act it

was his intention to commit, and warned him that such an attempt would precipitate

fresh disasters of unprecedented magnitude.

I have heard it stated by

Aqay-i-Kalim that in the course of that journey Baha'u'llah was able to meet Azim,

who had been endeavouring for a long time to see Him, and who in that interview

was advised, in the most emphatic terms, to abandon the plan he had conceived.

Baha'u'llah condemned his designs, dissociated Himself entirely from the act it

was his intention to commit, and warned him that such an attempt would precipitate

fresh disasters of unprecedented magnitude.

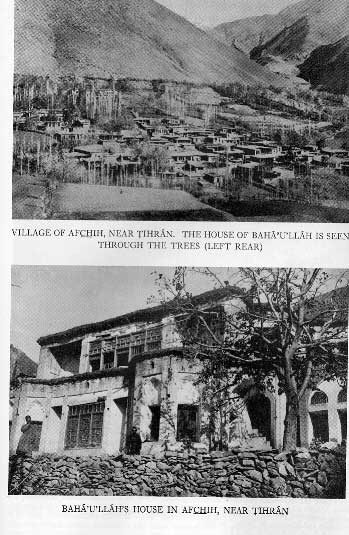

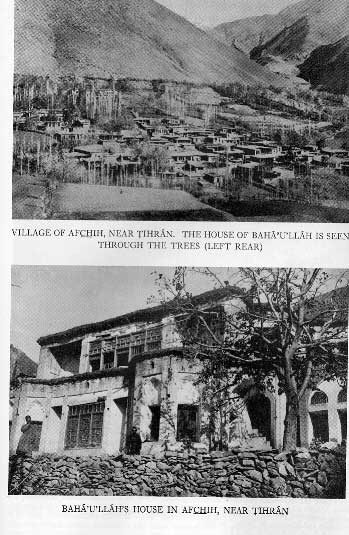

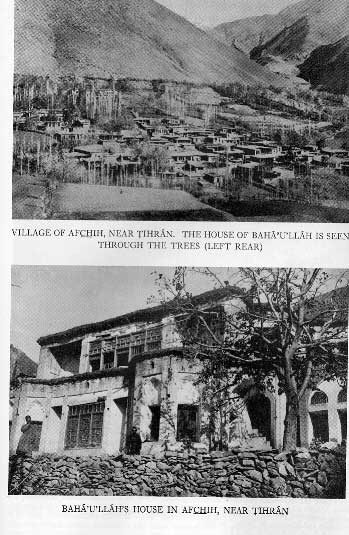

Baha'u'llah proceeded to

Lavasan, and was staying in the village of Afchih, the property of the Grand Vazir,

when the news of the attempt on the life of Nasiri'd-Din Shah reached Him. Ja'far-Quli

Khan was still acting as His host on behalf of the Amir-Nizam. That criminal act

was committed towards the end of the month of Shavval, in the year 1268 A.H.,(2)

by two obscure and irresponsible young men, one named Sadiq-i-Tabrizi, the other

Fathu'llah-i-Qumi, both of whom earned their livelihood in Tihran. At a time when

the imperial army, headed by the Shah himself, had encamped in Shimiran, these

two ignorant youths, in a frenzy of despair, arose to avenge the blood of their

slaughtered brethren.(3)

Baha'u'llah proceeded to

Lavasan, and was staying in the village of Afchih, the property of the Grand Vazir,

when the news of the attempt on the life of Nasiri'd-Din Shah reached Him. Ja'far-Quli

Khan was still acting as His host on behalf of the Amir-Nizam. That criminal act

was committed towards the end of the month of Shavval, in the year 1268 A.H.,(2)

by two obscure and irresponsible young men, one named Sadiq-i-Tabrizi, the other

Fathu'llah-i-Qumi, both of whom earned their livelihood in Tihran. At a time when

the imperial army, headed by the Shah himself, had encamped in Shimiran, these

two ignorant youths, in a frenzy of despair, arose to avenge the blood of their

slaughtered brethren.(3)

600

The folly that characterised

their act was betrayed by the fact that in making such an attempt on the life

of their sovereign, instead of employing effective weapons which would ensure

the success of their venture, these youths charged their pistols with shot which

no reasonable person would ever think of using for such a purpose. Had their action

been instigated by a man of judgment and common sense, he would certainly never

have allowed them to carry out their intention with such ridiculously ineffective

instruments.(1)

601

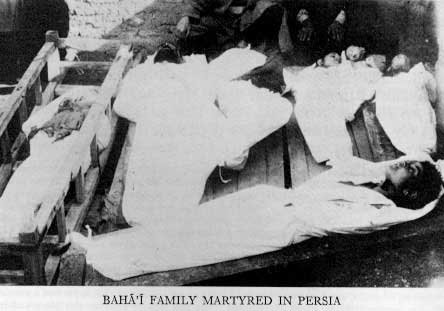

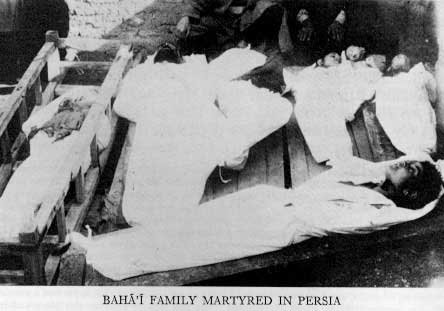

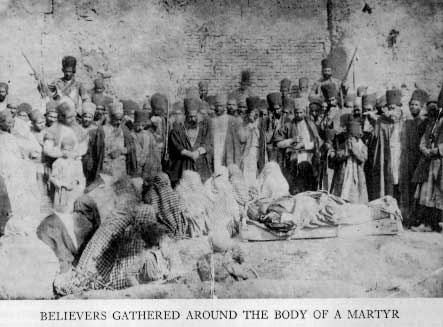

That act, though committed by wild and feeble-minded

fanatics, and in spite of its being from the very first emphatically condemned

by no less responsible a person than Baha'u'llah, was the signal for the outbreak

of a series of persecutions and massacres of such barbarous ferocity as could

be compared only to the atrocities of Mazindaran and Zanjan. The storm to which

that act gave rise plunged the whole of Tihran into consternation and distress.

It involved the life of the leading companions who had survived the calamities

to which their Faith had been so cruelly and repeatedly subjected. That storm

was still raging when Baha'u'llah, with some of His ablest lieutenants, was plunged

into a filthy, dark, and fever-stricken dungeon, whilst chains of such weight

as only notorious criminals were condemned to carry, were placed upon His neck.

For no less than four months He bore the burden, and such was the intensity of

His suffering that the marks of that cruelty remained imprinted upon His body

all the days of His life.

That act, though committed by wild and feeble-minded

fanatics, and in spite of its being from the very first emphatically condemned

by no less responsible a person than Baha'u'llah, was the signal for the outbreak

of a series of persecutions and massacres of such barbarous ferocity as could

be compared only to the atrocities of Mazindaran and Zanjan. The storm to which

that act gave rise plunged the whole of Tihran into consternation and distress.

It involved the life of the leading companions who had survived the calamities

to which their Faith had been so cruelly and repeatedly subjected. That storm

was still raging when Baha'u'llah, with some of His ablest lieutenants, was plunged

into a filthy, dark, and fever-stricken dungeon, whilst chains of such weight

as only notorious criminals were condemned to carry, were placed upon His neck.

For no less than four months He bore the burden, and such was the intensity of

His suffering that the marks of that cruelty remained imprinted upon His body

all the days of His life.

So grave a menace to their sovereign and to

the institutions of his realm stirred the indignation of the entire body of the

ecclesiastical order of Persia. To them so bold a deed called for immediate and

condign punishment. Measures of unprecedented severity, they clamoured, should

be undertaken to stem the tide that was engulfing both the government and the

Faith of Islam. Despite the restraint which the followers of the Bab had exercised

ever since the inception of the Faith in every part of the land; despite the repeated

charges of the chief disciples to their brethren enjoining them

So grave a menace to their sovereign and to

the institutions of his realm stirred the indignation of the entire body of the

ecclesiastical order of Persia. To them so bold a deed called for immediate and

condign punishment. Measures of unprecedented severity, they clamoured, should

be undertaken to stem the tide that was engulfing both the government and the

Faith of Islam. Despite the restraint which the followers of the Bab had exercised

ever since the inception of the Faith in every part of the land; despite the repeated

charges of the chief disciples to their brethren enjoining them

602

to refrain from acts of violence,

to obey their government loyally, and to disclaim any intention of a holy war,

their enemies persevered in their deliberate efforts to misrepresent the nature

and purpose of that Faith to the authorities. Now that an act of such momentous

consequences had been committed, what accusations would not these same enemies

be prompted to attribute to the Cause with which those guilty of the crime had

been associated! The moment seemed to have come when they could at last awaken

the rulers of the

country to the necessity of

extirpating as speedily as possible a heresy which seemed to threaten the very

foundations of the State.

country to the necessity of

extirpating as speedily as possible a heresy which seemed to threaten the very

foundations of the State.

Ja'far-Quli Khan, who was in Shimiran when

the attempt on the Shah's life was made, immediately wrote a letter to Baha'u'llah

and acquainted Him with what had happened. "The Shah's mother," he wrote, "is

inflamed with anger. She is denouncing you openly before the court and people

as the `would-be murderer' of her son. She is also trying to involve Mirza Aqa

Khan in this affair, and accuses him of being your accomplice." He urged Baha'u'llah

to remain for a time concealed in that neighbourhood, until the passion of the

populace had subsided. He despatched to Afchih an old and experienced messenger

whom he ordered to be at the

Ja'far-Quli Khan, who was in Shimiran when

the attempt on the Shah's life was made, immediately wrote a letter to Baha'u'llah

and acquainted Him with what had happened. "The Shah's mother," he wrote, "is

inflamed with anger. She is denouncing you openly before the court and people

as the `would-be murderer' of her son. She is also trying to involve Mirza Aqa

Khan in this affair, and accuses him of being your accomplice." He urged Baha'u'llah

to remain for a time concealed in that neighbourhood, until the passion of the

populace had subsided. He despatched to Afchih an old and experienced messenger

whom he ordered to be at the

603

disposal of his Guest and

to hold himself in readiness to accompany Him to whatever place of safety He might

desire.

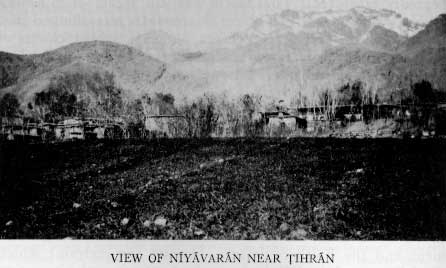

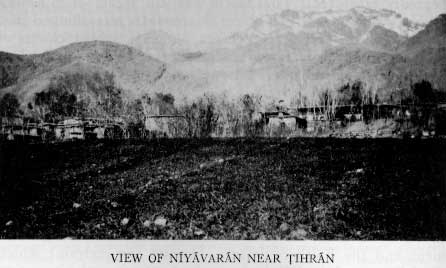

Baha'u'llah refused to avail Himself of the

opportunity Ja'far-Quli Khan offered Him. Ignoring the messenger and rejecting

his offer, He rode out, the next morning, with calm confidence, from Lavasan,

where He was sojourning, to the headquarters of the imperial army, which was then

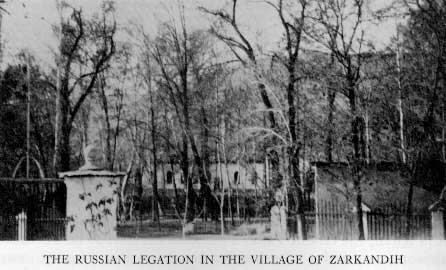

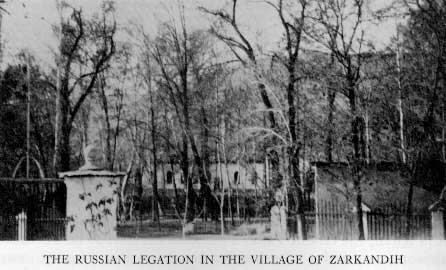

stationed in Niyavaran, in the Shimiran district. Arriving at the village of Zarkandih,

the seat of the Russian legation, which lay at a distance of one maydan(1)

from Niyavaran, He was met by Mirza Majid, His brother-in-law, who acted as secretary

to the Russian minister,(2)

and was invited by him to stay at his home, which adjoined that of his superior.

The attendants of Haji Ali Khan, the Hajibu'd-Dawlih, recognised Him and went

straightway to inform their master, who in turn brought the matter to the attention

of the Shah.

Baha'u'llah refused to avail Himself of the

opportunity Ja'far-Quli Khan offered Him. Ignoring the messenger and rejecting

his offer, He rode out, the next morning, with calm confidence, from Lavasan,

where He was sojourning, to the headquarters of the imperial army, which was then

stationed in Niyavaran, in the Shimiran district. Arriving at the village of Zarkandih,

the seat of the Russian legation, which lay at a distance of one maydan(1)

from Niyavaran, He was met by Mirza Majid, His brother-in-law, who acted as secretary

to the Russian minister,(2)

and was invited by him to stay at his home, which adjoined that of his superior.

The attendants of Haji Ali Khan, the Hajibu'd-Dawlih, recognised Him and went

straightway to inform their master, who in turn brought the matter to the attention

of the Shah.

The news of the arrival of Baha'u'llah greatly

surprised the officers of the imperial army. Nasiri'd-Din Shah himself was amazed

at the bold and unexpected step which a man who was accused of being the chief

instigator of the attempt upon his life had taken. He immediately sent one of

his trusted officers to the legation, demanding that the Accused be delivered

into his hands. The Russian minister refused, and requested Baha'u'llah to proceed

to the home of Mirza Aqa Khan, the Grand Vazir, a place he thought to be the most

appropriate under the circumstances. His request was granted, whereupon the minister

formally communicated to the Grand Vazir his desire that the utmost care should

be exercised to ensure the safety and protection of the Trust his government was

delivering into his keeping, warning him that he would hold him responsible should

he fail to disregard his wishes.(3)

The news of the arrival of Baha'u'llah greatly

surprised the officers of the imperial army. Nasiri'd-Din Shah himself was amazed

at the bold and unexpected step which a man who was accused of being the chief

instigator of the attempt upon his life had taken. He immediately sent one of

his trusted officers to the legation, demanding that the Accused be delivered

into his hands. The Russian minister refused, and requested Baha'u'llah to proceed

to the home of Mirza Aqa Khan, the Grand Vazir, a place he thought to be the most

appropriate under the circumstances. His request was granted, whereupon the minister

formally communicated to the Grand Vazir his desire that the utmost care should

be exercised to ensure the safety and protection of the Trust his government was

delivering into his keeping, warning him that he would hold him responsible should

he fail to disregard his wishes.(3)

Mirza Aqa Khan, though he undertook to give

the fullest assurances that were required, and received Baha'u'llah with every

mark of respect into his home, was, however, too apprehensive

Mirza Aqa Khan, though he undertook to give

the fullest assurances that were required, and received Baha'u'llah with every

mark of respect into his home, was, however, too apprehensive

604

for the safety of his own

position to accord his Guest the treatment he was expected to extend.

As Baha'u'llah was leaving the village of

Zarkandih, the minister's daughter, who felt greatly distressed at the dangers

which beset His life, was so overcome with emotion that she was unable to restrain

her tears. "Of what use," she was heard expostulating with her father, "is the

authority with which you have been invested, if you are powerless to extend your

protection to a guest whom you have received in your house?" The minister, who

had a great affection for his daughter, was moved by the sight of her tears, and

sought to com-

As Baha'u'llah was leaving the village of

Zarkandih, the minister's daughter, who felt greatly distressed at the dangers

which beset His life, was so overcome with emotion that she was unable to restrain

her tears. "Of what use," she was heard expostulating with her father, "is the

authority with which you have been invested, if you are powerless to extend your

protection to a guest whom you have received in your house?" The minister, who

had a great affection for his daughter, was moved by the sight of her tears, and

sought to com-

fort her by his assurances

that he would do all in his power to avert the danger that threatened the life

of Baha'u'llah.

fort her by his assurances

that he would do all in his power to avert the danger that threatened the life

of Baha'u'llah.

That day the army of Nasiri'd-Din Shah was

thrown into a state of violent tumult. The peremptory orders of the sovereign,

following so closely upon the attempt on his life, gave rise to the wildest rumours

and excited the fiercest passions in the hearts of the people of the, neighbourhood.

The agitation spread to Tihran and fanned into flaming fury the smouldering embers

of hatred which the enemies of the Cause still nourished ill their hearts. Confusion,

unprecedented in its range, reigned in the capital. A word of denunciation, a

sign, or a whisper was sufficient to subject the

That day the army of Nasiri'd-Din Shah was

thrown into a state of violent tumult. The peremptory orders of the sovereign,

following so closely upon the attempt on his life, gave rise to the wildest rumours

and excited the fiercest passions in the hearts of the people of the, neighbourhood.

The agitation spread to Tihran and fanned into flaming fury the smouldering embers

of hatred which the enemies of the Cause still nourished ill their hearts. Confusion,

unprecedented in its range, reigned in the capital. A word of denunciation, a

sign, or a whisper was sufficient to subject the

605

innocent to a persecution

which no pen dare try to describe. Security of life and property had completely

vanished. The highest ecclesiastical authorities in the capital joined hands with

the most influential members of the government to deal what they hoped would be

the fatal blow to a foe who, for eight years, had so gravely shaken the peace

of the land, and whom no cunning or violence had yet been able to silence.(1)

606

Baha'u'llah, now that the Bab was no more,

appeared in their eyes to be the arch-foe whom they deemed it their first duty

to seize and imprison. To them He was the reincarnation of the Spirit the Bab

had so powerfully manifested, the Spirit through which He had been able to accomplish

so complete a transformation in the lives and habits of His countrymen. The precautions

the Russian minister had taken, and the warning he had uttered, failed to stay

the hand that had been outstretched with such determination against that precious

Life.

Baha'u'llah, now that the Bab was no more,

appeared in their eyes to be the arch-foe whom they deemed it their first duty

to seize and imprison. To them He was the reincarnation of the Spirit the Bab

had so powerfully manifested, the Spirit through which He had been able to accomplish

so complete a transformation in the lives and habits of His countrymen. The precautions

the Russian minister had taken, and the warning he had uttered, failed to stay

the hand that had been outstretched with such determination against that precious

Life.

From Shimiran to Tihran, Baha'u'llah was several

times

From Shimiran to Tihran, Baha'u'llah was several

times

607

stripped of His garments,

and was overwhelmed with abuse and ridicule. On foot and exposed to the fierce

rays of the midsummer sun, He was compelled to cover, barefooted and bareheaded,

the whole distance from Shimiran to the dungeon already referred to. All along

the route, He was pelted and vilified by the crowds whom His enemies had succeeded

in convincing that He was the sworn enemy of their sovereign and the wrecker of

his realm. Words fail me to portray the horror of the treatment

which was meted out to Him as He was being taken to the Siyah-Chal(1)

of Tihran. As He was

approaching the dungeon, and

old and decrepit woman was seen to emerge from the midst of the crowd, with a

stone in her hand, eager to cast it at the face of Baha'u'llah. Her eyes glowed

with a determination and fanaticism of which few women of her age were capable.

Her whole frame shook with rage as she stepped forward and raised her hand to

hurl her missile at Him. "By the Siyyidu'sh-Shuhada,(2)

I adjure you," she pleaded, as she ran to overtake those into whose hands Baha'u'llah

had been delivered, "give me a chance to fling my stone in his face!" "Suffer

not this woman to be

approaching the dungeon, and

old and decrepit woman was seen to emerge from the midst of the crowd, with a

stone in her hand, eager to cast it at the face of Baha'u'llah. Her eyes glowed

with a determination and fanaticism of which few women of her age were capable.

Her whole frame shook with rage as she stepped forward and raised her hand to

hurl her missile at Him. "By the Siyyidu'sh-Shuhada,(2)

I adjure you," she pleaded, as she ran to overtake those into whose hands Baha'u'llah

had been delivered, "give me a chance to fling my stone in his face!" "Suffer

not this woman to be

608

disappointed," were Baha'u'llah's

words to His guards, as He saw her hastening behind Him. "Deny her not what she

regards as a meritorious act in the sight of God."

The Siyah-Chal, into which Baha'u'llah was

thrown, originally a reservoir of water for one of the public baths of Tihran,

was a subterranean dungeon in which criminals of the worst type were wont to be

confined. The darkness, the filth, and the character of the prisoners, combined

to make of that pestilential dungeon the most abominable place to which human

beings could be condemned. His feet were placed in stocks, and around His neck

were fastened the Qara-Guhar chains, infamous throughout Persia for their galling

weight.(1) For three days and

three nights, no manner of food or drink was given to Baha'u'llah. Rest and sleep

were both impossible to Him. The place was infested with vermin, and the stench

of that gloomy abode was enough to crush the very spirits of those who were condemned

to suffer its horrors. Such were the conditions under which He was held down that

even one of the executioners who were watching over Him was moved with pity. Several

times this man attempted to induce Him to take some tea which he had managed to

introduce into the dungeon under the cover of his garments. Baha'u'llah, however,

would refuse to drink it. His family often endeavoured to persuade the

The Siyah-Chal, into which Baha'u'llah was

thrown, originally a reservoir of water for one of the public baths of Tihran,

was a subterranean dungeon in which criminals of the worst type were wont to be

confined. The darkness, the filth, and the character of the prisoners, combined

to make of that pestilential dungeon the most abominable place to which human

beings could be condemned. His feet were placed in stocks, and around His neck

were fastened the Qara-Guhar chains, infamous throughout Persia for their galling

weight.(1) For three days and

three nights, no manner of food or drink was given to Baha'u'llah. Rest and sleep

were both impossible to Him. The place was infested with vermin, and the stench

of that gloomy abode was enough to crush the very spirits of those who were condemned

to suffer its horrors. Such were the conditions under which He was held down that

even one of the executioners who were watching over Him was moved with pity. Several

times this man attempted to induce Him to take some tea which he had managed to

introduce into the dungeon under the cover of his garments. Baha'u'llah, however,

would refuse to drink it. His family often endeavoured to persuade the

609

guards to allow them to carry

the food they had prepared for Him into His prison. Though at first no amount

of pleading would induce the guards to relax the severity of their discipline,

yet gradually they yielded to His friends' importunity. No one could be sure,

however, whether that food would eventually reach Him, or whether He would consent

to eat it whilst a number of His fellow-prisoners were starving before His eyes.

Surely greater misery than had befallen these innocent victims of the wrath of

their sovereign, could hardly be imagined.(1)

As to the youth Sadiq-i-Tabrizi,

the fate he suffered was as cruel as it was humiliating. He was seized at the

moment he was rushing towards the Shah, whom he had thrown from his horse, hoping

to strike him with the sword he held in his hand. The Shatir-Bashi, together with

the Mustawfiyu'l-Mamalik's attendants, fell upon him and, without attempting to

learn who he was, slew him on the spot. Wishing to allay the excitement of the

populace, they hewed his body into two halves, each of which they suspended to

the public

As to the youth Sadiq-i-Tabrizi,

the fate he suffered was as cruel as it was humiliating. He was seized at the

moment he was rushing towards the Shah, whom he had thrown from his horse, hoping

to strike him with the sword he held in his hand. The Shatir-Bashi, together with

the Mustawfiyu'l-Mamalik's attendants, fell upon him and, without attempting to

learn who he was, slew him on the spot. Wishing to allay the excitement of the

populace, they hewed his body into two halves, each of which they suspended to

the public

610

gaze at the entrance of the

gates of Shimiran and Shah-'Abdu'l-'Azim.(1)

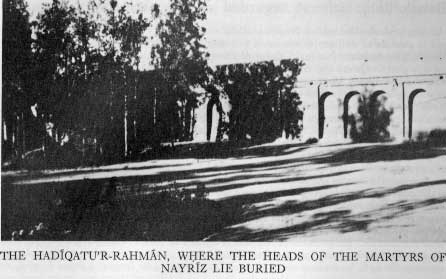

His two other companions, Fathu'llah-i-Hakkak-i-Qumi and Haji Qasim-i-Nayrizi,

who had succeeded in inflicting only slight wounds on the Shah, were subjected

to inhuman treatment, to which they ultimately owed their death. Fathu'llah, though

suffering unspeakable cruelties, obstinately refused to answer the questions they

asked him. The silence he maintained in the face of manifold tortures, induced

his persecutors to believe that he was devoid of the

power of speech. Exasperated

by the failure of their efforts, they poured molten lead down his throat, an act

which brought his sufferings to an end.

power of speech. Exasperated

by the failure of their efforts, they poured molten lead down his throat, an act

which brought his sufferings to an end.

His comrade, Haji Qasim,

was treated with a savagery still more revolting. On the very day Haji Sulayman

Khan was being subjected to that terrible ordeal, this poor wretch was receiving

similar treatment at the hands of his persecutors in Shimiran. He was stripped

of his clothes, lighted 610-1.htm

His comrade, Haji Qasim,

was treated with a savagery still more revolting. On the very day Haji Sulayman

Khan was being subjected to that terrible ordeal, this poor wretch was receiving

similar treatment at the hands of his persecutors in Shimiran. He was stripped

of his clothes, lighted 610-1.htm

611

candles were thrust into

holes driven into his flesh, and he was thus paraded before the eyes of a multitude

who yelled and cursed him. The spirit of revenge that animated those into whose

hands he was delivered seemed insatiable. Day after day fresh victims were forced

to expiate with their blood a crime which they had never committed, and of the

circumstances of which they were wholly ignorant. Every ingenious device that

the torture-mongers of Tihran could employ was applied with merciless severity

to the bodies of

these unfortunate ones who

were neither brought to trial nor questioned, and whose right to plead and prove

their innocence was entirely ignored.

these unfortunate ones who

were neither brought to trial nor questioned, and whose right to plead and prove

their innocence was entirely ignored.

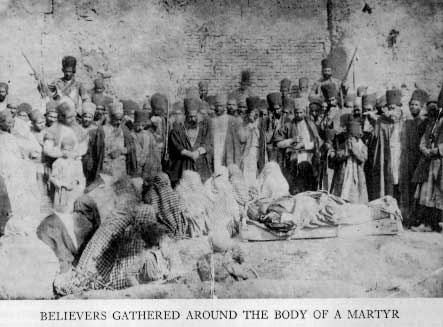

Each of those days of terror witnessed the

martyrdom of two companions of the Bab, one of whom was slain in Tihran, whilst

the other met his fate in Shimiran. Both were subjected to the same manner of

torture, both were handed over to the public to wreak their vengeance upon them.

Those arrested were distributed among the various classes of people, whose messengers

would visit the dungeon each day and claim their

Each of those days of terror witnessed the

martyrdom of two companions of the Bab, one of whom was slain in Tihran, whilst

the other met his fate in Shimiran. Both were subjected to the same manner of

torture, both were handed over to the public to wreak their vengeance upon them.

Those arrested were distributed among the various classes of people, whose messengers

would visit the dungeon each day and claim their

612

victim.(1)

Conducting him to the scene of his death, they would give the signal for a general

attack upon him, whereupon men and women would close upon their prey, tear his

body to pieces, and so mutilate it that no trace of its original form would remain.

Such ruthlessness amazed even the most brutal of the executioners, whose hands,

however much accustomed to human slaughter, had never perpetrated the atrocities

of which those people had proved themselves capable.(2)

613

Of all the tortures which an insatiable enemy

inflicted upon its victims, none was more revolting in its character than that

which characterised the death of Haji Sulayman Khan. He was the son of Yahya Khan,

one of the officers in the service of the Nayibu's-Saltanih, who was the father

of Muhammad Shah. He retained that same position in the early days of the reign

of Muhammad Shah. Haji Sulayman Khan showed from his earliest years a marked disinclination

to rank and office. Ever since the day of his acceptance of

Of all the tortures which an insatiable enemy

inflicted upon its victims, none was more revolting in its character than that

which characterised the death of Haji Sulayman Khan. He was the son of Yahya Khan,

one of the officers in the service of the Nayibu's-Saltanih, who was the father

of Muhammad Shah. He retained that same position in the early days of the reign

of Muhammad Shah. Haji Sulayman Khan showed from his earliest years a marked disinclination

to rank and office. Ever since the day of his acceptance of

614

the Cause of the Bab, the

petty pursuits in which the people around him were immersed excited his pity and

contempt. The vanity of their ambitions had been abundantly demonstrated in his

eyes. In his early youth, he felt a longing to escape from the turmoil of the

capital and to seek refuge in the holy city of Karbila. There he met Siyyid Kazim

and grew to be one of his most ardent supporters. His sincere piety, his frugality

and love of seclusion were among the chief traits of his character. He tarried

in Karbila until the day when the Call from Shiraz reached him through Mulla Yusuf-i-Ardibili

and Mulla Mihdiy-Ku'i, both of whom were among his best-known friends. He enthusiastically

embraced the Message of the Bab.(1)

He had intended, upon his return from Karbila to Tihran, to join the defenders

of the fort of Tabarsi, but arrived too late to achieve his purpose. He remained

in the capital and continued to wear the kind of dress he had adopted in Karbila.

The small turban he wore, and the white tunic which his black

aba(2) concealed, were displeasing

to the Amir-Nizam, who induced him to discard these garments and to clothe himself

instead in a

615

military uniform. He was

made to wear the kulah,(1)

a head-dress that was thought to be more in accordance with the rank his father

held. Though the Amir insisted that he should accept a position in the service

of the government, he obstinately refused to comply with his request. Most of

his time was spent in the company of the disciples of the Bab, particularly those

of His companions who had survived the struggle of Tabarsi. He surrounded them

with a care and kindness truly surprising. He and his father were so influential

that the Amir-Nizam was induced to spare his life and indeed to refrain from any

acts of violence against him. Though he was present in Tihran when the seven companions

of the Bab, with whom he was intimately associated, were martyred, neither the

officials of the government nor any of the common people ventured to demand his

arrest. Even in Tabriz, whither he had journeyed for the purpose of saving the

life of the Bab, not one among the inhabitants of that city dared to lift a finger

against him. The Amir-Nizam, who was duly informed of all his services to the

Cause of the Bab, preferred to ignore his acts rather than precipitate a conflict

with him and his father.

Soon after the martyrdom of a certain Mulla

Zaynu'l-'Abidin-i-Yazdi, a rumour was spread that those whom the government intended

to put to death, among whom were Siyyid Husayn, the Bab's amanuensis, and Tahirih,

were to be released and that further persecution of their friends was to be definitely

abandoned. It was reported far and wide that the Amir-Nizam, deeming the hour

of his death to be approaching, had been seized suddenly with a great fear and,

in an agony of repentance, had exclaimed: "I am haunted by the vision of the Siyyid-i-Bab,

whom I have caused to be martyred. I can now see the fearful mistake I have made.

I should have restrained the violence of those who pressed me to shed his blood

and that of his companions. I now perceive that the interests of the State required

it." His successor, Mirza Aqa Khan, was similarly inclined in the early days of

his administration, and was intending to inaugurate his ministry with a lasting

reconciliation between him and the followers of the Bab. He was preparing to

Soon after the martyrdom of a certain Mulla

Zaynu'l-'Abidin-i-Yazdi, a rumour was spread that those whom the government intended

to put to death, among whom were Siyyid Husayn, the Bab's amanuensis, and Tahirih,

were to be released and that further persecution of their friends was to be definitely

abandoned. It was reported far and wide that the Amir-Nizam, deeming the hour

of his death to be approaching, had been seized suddenly with a great fear and,

in an agony of repentance, had exclaimed: "I am haunted by the vision of the Siyyid-i-Bab,

whom I have caused to be martyred. I can now see the fearful mistake I have made.

I should have restrained the violence of those who pressed me to shed his blood

and that of his companions. I now perceive that the interests of the State required

it." His successor, Mirza Aqa Khan, was similarly inclined in the early days of

his administration, and was intending to inaugurate his ministry with a lasting

reconciliation between him and the followers of the Bab. He was preparing to

616

undertake that task when

the attempt on the life of the Shah shattered his plans and threw the capital

into a state of unprecedented confusion.

I have heard the Most Great Branch,(1)

who in those days was a child of only eight years of age, recount one of His experiences

as He ventured to leave the house in which He was then residing. "We had sought

shelter, He told us, "in the house of My uncle, Mirza Isma'il. Tihran was in the

throes of the wildest excitement. I ventured at times to sally forth from that

house and to cross the street on My way to the market. I would hardly cross the

threshold and step into the street, when boys of My age, who were running about,

would crowd around Me crying, `Babi! Babi. Knowing well the state of excitement

into which all the inhabitants of the capital, both young and old, had fallen,

I would deliberately ignore their clamour and quietly steal away to My home. One

day I happened to be walking alone through the market on My way to My uncle's

house. As I was looking behind Me, I found a band of little ruffians running fast

to overtake Me. They were pelting Me with stones and shouting menacingly, `Babi!

Babi!' To intimidate them seemed to be the only way I could avert the danger with

which I was threatened. I turned back and rushed towards them with such determination

that they fled away in distress and vanished. I could hear their distant cry,

`The little Babi is fast pursuing us! He will surely overtake and slay us all!'

As I was directing My steps towards home, I heard a man shouting at the top of

his voice: `Well done, you brave and fearless child! No one of your age would

ever have been able, unaided, to withstand their attack.' From that day onward,

I was never again molested by any of the boys of the streets, nor did I hear any

offensive word fall from their lips."

I have heard the Most Great Branch,(1)

who in those days was a child of only eight years of age, recount one of His experiences

as He ventured to leave the house in which He was then residing. "We had sought

shelter, He told us, "in the house of My uncle, Mirza Isma'il. Tihran was in the

throes of the wildest excitement. I ventured at times to sally forth from that

house and to cross the street on My way to the market. I would hardly cross the

threshold and step into the street, when boys of My age, who were running about,

would crowd around Me crying, `Babi! Babi. Knowing well the state of excitement

into which all the inhabitants of the capital, both young and old, had fallen,

I would deliberately ignore their clamour and quietly steal away to My home. One

day I happened to be walking alone through the market on My way to My uncle's

house. As I was looking behind Me, I found a band of little ruffians running fast

to overtake Me. They were pelting Me with stones and shouting menacingly, `Babi!

Babi!' To intimidate them seemed to be the only way I could avert the danger with

which I was threatened. I turned back and rushed towards them with such determination

that they fled away in distress and vanished. I could hear their distant cry,

`The little Babi is fast pursuing us! He will surely overtake and slay us all!'

As I was directing My steps towards home, I heard a man shouting at the top of

his voice: `Well done, you brave and fearless child! No one of your age would

ever have been able, unaided, to withstand their attack.' From that day onward,

I was never again molested by any of the boys of the streets, nor did I hear any

offensive word fall from their lips."

Among those who, in the midst of the general

confusion, were seized and thrown into prison was Haji Sulayman Khan, the circumstances

of whose martyrdom I now proceed to relate. The facts I mention have been carefully

sifted and verified by me, and I owe them, for the most part, to Aqay-i-Kalim,

who was himself in those days in Tihran and was made

Among those who, in the midst of the general

confusion, were seized and thrown into prison was Haji Sulayman Khan, the circumstances

of whose martyrdom I now proceed to relate. The facts I mention have been carefully

sifted and verified by me, and I owe them, for the most part, to Aqay-i-Kalim,

who was himself in those days in Tihran and was made

617

to share the terrors and

sufferings of his brethren. "On the very day of Haji Sulayman Khan's martyrdom,"

he informed me, "I happened to be present, with Mirza Abdu'l-Majid, at a gathering

in Tihran at which a considerable number of the notables and dignitaries of the

capital were present. Among them was Haji Mulla Mahmud, the Nizamu'l-'Ulama, who

requested the Kalantar to describe the actual circumstances of the death of Haji

Sulayman Khan. The Kalantar motioned with his finger to Mirza Taqi, the kad-khuda(1)

who, he said, had conducted the victim from the vicinity of the imperial palace

to the place of his execution, outside the gate of Naw. Mirza Taqi was accordingly

requested to relate to those present all that he had seen and heard. `I and my

assistants,' he said, `were ordered to purchase nine candles and to thrust them,

ourselves into deep holes we were to cut in his flesh. We were instructed to light

each one of these candles and to conduct him through the market to the accompaniment

of drums and trumpets as far as the place of his execution. There we were ordered

to hew his body into two halves, each of which we were asked to suspend on either

side of the gate of Naw. He himself chose the manner in which he wished to be

martyred. Hajibu'd-Dawlih(2)

had been commanded by Nasiri'd-Din Shah to enquire into the complicity of the

accused, and, if assured of his innocence, to induce him to recant. If he submitted,

his life was to be spared and he was to be detained pending the final settlement

of his case. In the event of his refusal, he was to be put to death in whatever

manner he himself might desire.

"`The investigation of hajibu'd-Dawlih convinced

him of the innocence of Haji Sulayman Khan. The accused, as soon as he had been

informed of the instructions of his sovereign, was heard joyously exclaiming:

"Never, so long as my life-blood continues to pulsate in my veins, shall I be

willing to recant my faith in my Beloved! This world which the Commander of the

Faithful(3) has likened to carrion

will never allure me from my heart's Desire." He was asked to

"`The investigation of hajibu'd-Dawlih convinced

him of the innocence of Haji Sulayman Khan. The accused, as soon as he had been

informed of the instructions of his sovereign, was heard joyously exclaiming:

"Never, so long as my life-blood continues to pulsate in my veins, shall I be

willing to recant my faith in my Beloved! This world which the Commander of the

Faithful(3) has likened to carrion

will never allure me from my heart's Desire." He was asked to

618

determine the manner in which

he wished to die. "Pierce holes in my flesh," was the instant reply, "and in each

wound place a candle. Let nine candles be lighted all over my body, and in this

state conduct me through the streets of Tihran. Summon the multitude to witness

the glory of my martyrdom, so that the memory of my death may remain imprinted

in their hearts and help them, as they recall the intensity of my tribulation,

to recognise the Light I have embraced. After I have reached the foot of the gallows

and have uttered the last prayer of my earthly life, cleave my body in twain and

suspend my limbs on either side of the gate of Tihran, that the multitude passing

beneath it may witness to the love which the Faith of the Bab has kindled in the

hearts of His disciples, and may look upon the proofs of their devotion."

"`Hajibu'd-Dawlih instructed

his men to abide by the expressed wishes of Haji Sulayman Khan, and charged me

to conduct him through the market as far as the place of his execution. As they

handed to the victim the candles they had purchased, and were preparing to thrust

their knives into his breast, he made a sudden attempt to seize the weapon from

the executioner's trembling hands in order to plunge it himself into his flesh.

"Why fear and hesitate?" he cried, as he stretched forth his arm to snatch the

knife from his grasp. "Let me myself perform the deed and light the candles."

Fearing lest he should attack us, I ordered my men to resist his attempt and bade

them tie his hands behind his back. "Let me," he pleaded, point out with my fingers

the places into which I wish them to thrust their dagger, for I have no other

request to make besides this."

"`Hajibu'd-Dawlih instructed

his men to abide by the expressed wishes of Haji Sulayman Khan, and charged me

to conduct him through the market as far as the place of his execution. As they

handed to the victim the candles they had purchased, and were preparing to thrust

their knives into his breast, he made a sudden attempt to seize the weapon from

the executioner's trembling hands in order to plunge it himself into his flesh.

"Why fear and hesitate?" he cried, as he stretched forth his arm to snatch the

knife from his grasp. "Let me myself perform the deed and light the candles."

Fearing lest he should attack us, I ordered my men to resist his attempt and bade

them tie his hands behind his back. "Let me," he pleaded, point out with my fingers

the places into which I wish them to thrust their dagger, for I have no other

request to make besides this."

"`He asked them to pierce two holes in his

breast, two in his shoulders, one in the nape of his neck, and the four others

in his back. With stoic calm he endured those tortures. Steadfastness glowed in

his eyes as he maintained a mysterious and unbroken silence. Neither the howling

of the multitude nor the sight of the blood that streamed all over his body could

induce him to interrupt that silence. Impassive and serene he remained until all

the nine candles were placed in position and lighted.

"`He asked them to pierce two holes in his

breast, two in his shoulders, one in the nape of his neck, and the four others

in his back. With stoic calm he endured those tortures. Steadfastness glowed in

his eyes as he maintained a mysterious and unbroken silence. Neither the howling

of the multitude nor the sight of the blood that streamed all over his body could

induce him to interrupt that silence. Impassive and serene he remained until all

the nine candles were placed in position and lighted.

"`When all was completed for his march to

the scene

"`When all was completed for his march to

the scene

619

of his death, he, standing

erect as an arrow and with that same unflinching fortitude gleaming upon his face,

stepped forward to lead the concourse that was pressing round him to the place

that was to witness the consummation of his martyrdom. Every few steps he would

interrupt his march and, gazing at the bewildered bystanders, would shout: "What

greater pomp and pageantry than those which this day accompany my progress to

win the crown of glory! Glorified be the Bab, who can kindle such devotion in

the breasts of His lovers, and can endow them with a power greater than the might

of kings!" At times, as if intoxicated with the fervour of that devotion, he would

exclaim: "The Abraham of a bygone age, as He prayed God, in the hour of bitter

agony, to send down upon Him the refreshment for which His soul was crying, heard

the voice of the Unseen proclaim: `O fire! Be thou cold, and to Abraham a safety!'(1)

But this Sulayman is crying out from the depths of his ravaged heart: `Lord, Lord,

let Thy fire burn unceasingly within me, and suffer its flame to consume my being.'"

As his eyes saw the wax flicker in his wounds, he burst forth in an acclamation

of frantic delight: "Would that He whose hand has enkindled my soul were here

to behold my state!" "Think me not to be intoxicated with the wine of this earth!"

he cried to the vast throng who stood aghast at the sight of his behaviour. It

is the love of my Beloved that has filled my soul and made me feel endowed with

a sovereignty which even kings might envy!"

"`I cannot recall the exclamations of joy

which fell from his lips as he drew near to his end. All I remember are but a

few of the stirring words which, in his moments of exultation, he was moved to

cry out to the concourse of spectators. Words fail me to portray the expression

of that countenance or to measure the effect of his words on the multitude.

"`I cannot recall the exclamations of joy

which fell from his lips as he drew near to his end. All I remember are but a

few of the stirring words which, in his moments of exultation, he was moved to

cry out to the concourse of spectators. Words fail me to portray the expression

of that countenance or to measure the effect of his words on the multitude.

"`He was still in the bazaar when the blowing

of a breeze excited the burning of the candles that were placed upon his breast.

As they melted rapidly, their flames reached the level of the wounds into which

they had been thrust. We who were following a few steps behind him could hear

distinctly the sizzling of his flesh. The sight of gore and fire

"`He was still in the bazaar when the blowing

of a breeze excited the burning of the candles that were placed upon his breast.

As they melted rapidly, their flames reached the level of the wounds into which

they had been thrust. We who were following a few steps behind him could hear

distinctly the sizzling of his flesh. The sight of gore and fire

620

which covered his body, instead

of silencing his voice, appeared to heighten his unquenchable enthusiasm. He could

still be heard, this time addressing the flames, as they ate into his wounds:

"You have long lost your sting, O flames, and have been robbed of your power to

pain me. Make haste, for from your very tongues of fire I can hear the voice that

calls me to my Beloved!"

"`Pain and suffering seemed to have melted

away in the ardour of that enthusiasm. Enveloped by the flames, he walked as a

conqueror might have marched to the scene of his victory. He moved through the

excited crowd a blaze of light amidst the gloom that surrounded him. Arriving

at the foot of the gallows, he again raised his voice in a last appeal to the

multitude of onlookers: "Did not this Sulayman whom you now see before you a prey

to fire and blood, enjoy until recently all the favours and riches the world can

bestow? What could have caused him to renounce this earthly glory and accept in

return such great degradation and suffering?" Prostrating himself in the direction

of the shrine of the Imam-Zadih Hasan, he murmured certain words in Arabic which

I could not understand. "My work is now finished!" he cried to the executioner,

as soon as his prayer was ended. "Come and do yours!" He was still alive when

his body was hewn into two halves with a hatchet. The praise of his Beloved, despite

such incredible sufferings, lingered upon his lips until the last moment of his

life.'(1)

"`Pain and suffering seemed to have melted

away in the ardour of that enthusiasm. Enveloped by the flames, he walked as a

conqueror might have marched to the scene of his victory. He moved through the

excited crowd a blaze of light amidst the gloom that surrounded him. Arriving

at the foot of the gallows, he again raised his voice in a last appeal to the

multitude of onlookers: "Did not this Sulayman whom you now see before you a prey

to fire and blood, enjoy until recently all the favours and riches the world can

bestow? What could have caused him to renounce this earthly glory and accept in

return such great degradation and suffering?" Prostrating himself in the direction

of the shrine of the Imam-Zadih Hasan, he murmured certain words in Arabic which

I could not understand. "My work is now finished!" he cried to the executioner,

as soon as his prayer was ended. "Come and do yours!" He was still alive when

his body was hewn into two halves with a hatchet. The praise of his Beloved, despite

such incredible sufferings, lingered upon his lips until the last moment of his

life.'(1)

"That tragic tale stirred the listeners to

the very depths of their souls. The Nizamu'l-'Ulama, who was listening intently

"That tragic tale stirred the listeners to

the very depths of their souls. The Nizamu'l-'Ulama, who was listening intently

621

to all its details, wrung

his hands in horror and despair. How strange, how very strange, is this Cause!'

he exclaimed. Without adding a further word of comment, he, immediately after,

arose and departed."(1)

Those days of unceasing turmoil witnessed the

martyrdom of yet another eminent disciple of the Bab. A woman, no less great and

heroic than Tahirih herself, was engulfed in the storm that was then raging with

undiminished violence throughout the capital. What I now begin to relate regarding

the circumstances of her martyrdom has been obtained from trustworthy informants,

some of whom were themselves witnesses of the events I am attempting to describe.

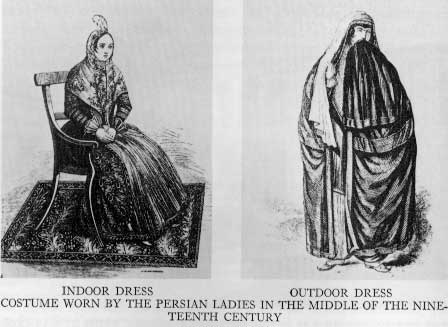

Her stay in Tihran was marked by many proofs of the warm

Those days of unceasing turmoil witnessed the

martyrdom of yet another eminent disciple of the Bab. A woman, no less great and

heroic than Tahirih herself, was engulfed in the storm that was then raging with

undiminished violence throughout the capital. What I now begin to relate regarding

the circumstances of her martyrdom has been obtained from trustworthy informants,

some of whom were themselves witnesses of the events I am attempting to describe.

Her stay in Tihran was marked by many proofs of the warm

622

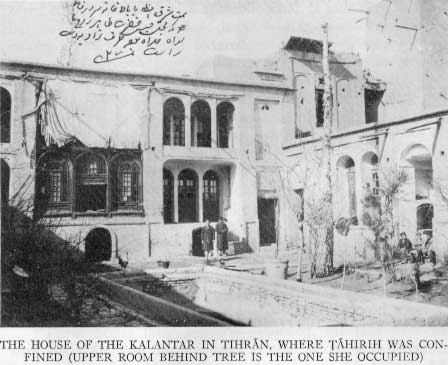

affection and high esteem

in which she was held by the leading women of the capital. She had reached, indeed,

in those days, the high-water mark of her popularity.(1)

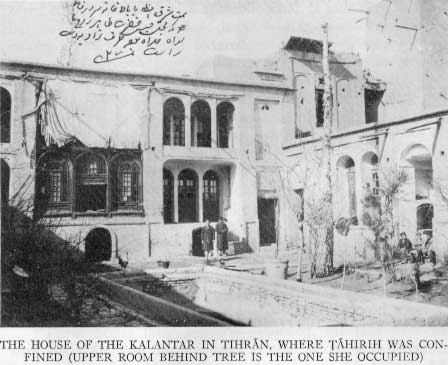

The house where she was confined was besieged by her women admirers, who thronged

her doors, eager to enter her presence and to seek the benefit of her knowledge.(2)

Among these ladies, the wife of Kalantar(3)

distinguished herself by the extreme reverence she showed to Tahirih. Acting as

her hostess, she introduced into her presence the flower of womanhood in Tihran,

served her with extraordinary enthusiasm, and never failed to contribute her share

in deepening her influence among her womenfolk. Persons with whom the wife of

Kalantar was intimately connected have heard her relate the following: "One night,

whilst Tahirih was staying in my home, I was summoned to her presence and found

her fully adorned, dressed in a gown of snow-white silk. Her room was redolent

with the choicest perfume. I expressed to her my surprise at so unusual a sight.

`I am preparing to meet my Beloved,' she said, `and wish to free you from the

cares

623

and anxieties of my imprisonment.'

I was much startled at first, and wept at the thought of separation from her.

`Weep not, she sought to reassure me. `The time of your lamentation is not yet

come. I wish to share with you my last wishes, for the hour when I shall be arrested

and condemned to suffer martyrdom is fast approaching. I would request you to

allow your son to accompany me to the scene of my death and to ensure that the

guards and executioner into whose

hands I shall be delivered

will not compel me to divest myself of this attire. It is also my wish that my

body be thrown into a pit, and that that pit be filled with earth and stones.

Three days after my death a woman will come and visit you, to whom you will give

this package which I now deliver into your hands. My last request is that you

permit no one henceforth to enter my chamber. From now until the time when I shall

be summoned to leave this house, let no one be allowed to disturb my devotions.

This day I intend to fast-- a fast which I shall not break until I am brought

face to face

hands I shall be delivered

will not compel me to divest myself of this attire. It is also my wish that my

body be thrown into a pit, and that that pit be filled with earth and stones.

Three days after my death a woman will come and visit you, to whom you will give

this package which I now deliver into your hands. My last request is that you

permit no one henceforth to enter my chamber. From now until the time when I shall

be summoned to leave this house, let no one be allowed to disturb my devotions.

This day I intend to fast-- a fast which I shall not break until I am brought

face to face

624

with my Beloved.' She bade

me, with these words, lock the door of her chamber and not open it until the hour

of her departure should strike. She also urged me to keep secret the tidings of

her death until such time as her enemies should themselves disclose it.

"The great love I cherished for her in my

heart, alone enabled me to abide by her instructions. But for the compelling desire

I felt to fulfil her wishes, I would never have consented to deprive myself of

one moment of her presence.

"The great love I cherished for her in my

heart, alone enabled me to abide by her instructions. But for the compelling desire

I felt to fulfil her wishes, I would never have consented to deprive myself of

one moment of her presence.

I locked the door of her chamber

and retired to my own, in a state of uncontrollable sorrow. I lay sleepless and

disconsolate upon my bed. The thought of her approaching martyrdom lacerated my

soul. `Lord, Lord,' I prayed in my despair, `turn from her, if it be Thy wish,

the cup which her lips desire to drink.' That day and night, I several times,

unable to contain myself, arose and stole away to the threshold of that room and

stood silently at her door, eager to listen to whatever might be falling from

her lips. I was enchanted by the melody of that voice which intoned the praise

of her Beloved. I could hardly remain standing upon my feet, so

I locked the door of her chamber

and retired to my own, in a state of uncontrollable sorrow. I lay sleepless and

disconsolate upon my bed. The thought of her approaching martyrdom lacerated my

soul. `Lord, Lord,' I prayed in my despair, `turn from her, if it be Thy wish,

the cup which her lips desire to drink.' That day and night, I several times,

unable to contain myself, arose and stole away to the threshold of that room and

stood silently at her door, eager to listen to whatever might be falling from

her lips. I was enchanted by the melody of that voice which intoned the praise

of her Beloved. I could hardly remain standing upon my feet, so

625

great was my agitation. Four

hours after sunset, I heard a knocking at the door. I hastened immediately to

my son, and acquainted him with the wishes of Tahirih. He pledged his word that

he would fulfil every instruction she had given me. It chanced that night that

my husband was absent. My son, who opened the door, informed me that the farrashes(1)

of Aziz Khan-i-Sardar were standing at the gate, demanding that Tahirih be immediately

delivered into their hands. I was struck with terror by the news, and, as I tottered

to her door and with trembling hands unlocked it, found her veiled and prepared

to leave her apartment. She was pacing the floor when I entered, and was chanting

a litany expressive of both grief and triumph. As soon as she saw me, she approached

and kissed me. She placed in my hand the key to her chest, in which she said she

had left for me a few trivial things as a remembrance of her stay in my house.

Whenever you open this chest,' she said, `and behold the things it contains, you

will, I hope, remember me and rejoice in my gladness.'

"With these words she bade me her last farewell,

and, accompanied by my son, disappeared from before my eyes. What pangs of anguish

I felt that moment, as I beheld her beauteous form gradually fade away in the

distance! She mounted the steed which the Sardar had sent for her, and, escorted

by my son and a number of attendants, who marched on each side of her, rode out

to the garden that was to be the scene of her martyrdom.

"With these words she bade me her last farewell,

and, accompanied by my son, disappeared from before my eyes. What pangs of anguish

I felt that moment, as I beheld her beauteous form gradually fade away in the

distance! She mounted the steed which the Sardar had sent for her, and, escorted

by my son and a number of attendants, who marched on each side of her, rode out

to the garden that was to be the scene of her martyrdom.

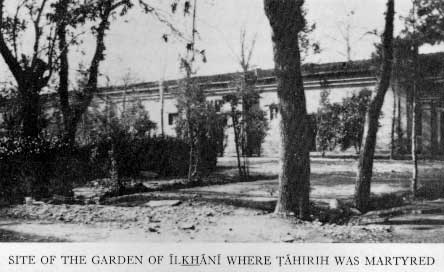

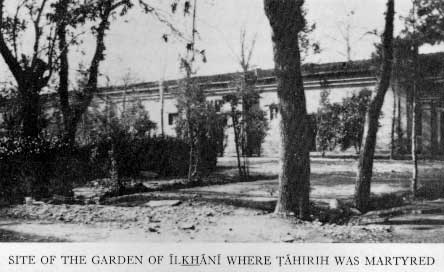

"Three hours later my son returned, his face

drenched with tears, hurling imprecations at the Sardar and his abject lieutenants.

I tried to calm his agitation, and, seating him beside me, asked him to relate

as fully as he could the circumstances of her death. `Mother,' he sobbingly replied,

`I can scarcely attempt to describe what my eyes have beheld. We straightway proceeded

to the Ilkhani garden,(2)

"Three hours later my son returned, his face

drenched with tears, hurling imprecations at the Sardar and his abject lieutenants.

I tried to calm his agitation, and, seating him beside me, asked him to relate

as fully as he could the circumstances of her death. `Mother,' he sobbingly replied,

`I can scarcely attempt to describe what my eyes have beheld. We straightway proceeded

to the Ilkhani garden,(2)

626

outside the gate of the city.

There I found, to my horror, the Sardar and his lieutenants absorbed in acts of

debauchery and shame, flushed with wine and roaring with laughter. Arriving at

the gate, Tahirih dismounted and, calling me to her, asked me to act as her intermediary

with the Sardar, whom she said she was disinclined to address in the midst of

his revelry. `They apparently wish to strangle me,' she said. `I set aside, long

ago, a silken kerchief which I hoped would be used for this purpose. I deliver

it into your hands and wish you to induce that dissolute drunkard to use it as

a means whereby he can take my life.'

"When I went to the Sardar, I found him in

a state of wretched intoxication. `Interrupt not the gaiety of our festival!'

I heard him shout as I approached him. `Let that miserable wretch be strangled

and her body be thrown into a pit!' I was greatly surprised at such an order.

Believing it unnecessary to venture any request from him, I went to two of his

attendants, with whom I was already acquainted, and gave them the kerchief with

which Tahirih had entrusted me. They consented to grant her request. That same

kerchief was wound round her neck and was made the instrument of her martyrdom.

I hastened immediately afterwards to the gardener and asked him whether

"When I went to the Sardar, I found him in

a state of wretched intoxication. `Interrupt not the gaiety of our festival!'

I heard him shout as I approached him. `Let that miserable wretch be strangled

and her body be thrown into a pit!' I was greatly surprised at such an order.

Believing it unnecessary to venture any request from him, I went to two of his

attendants, with whom I was already acquainted, and gave them the kerchief with

which Tahirih had entrusted me. They consented to grant her request. That same

kerchief was wound round her neck and was made the instrument of her martyrdom.

I hastened immediately afterwards to the gardener and asked him whether

627

he could suggest a place

where I could conceal the body. He directed me, to my great delight, to a well

that had been dug recently and left unfinished. With the help of a few others,

I lowered her into her grave and filled the well with earth and stones in the

manner she herself had wished. Those who saw her in her last moments were profoundly

affected. With downcast eyes and rapt in silence, they mournfully dispersed, leaving

their victim, who had shed so imperishable a lustre upon their country, buried

beneath a mass of stones which they, with their own hands, had heaped upon her.

I wept hot tears as my son unfolded to my

eyes that tragic tale. I was so overcome with emotion that I fell prostrate and

unconscious upon the ground. When I had recovered, I found my son a prey to an

agony no less severe than my own. He lay upon his couch, weeping in a passion

of devotion. Beholding my plight, he approached and comforted me. `Your tears,'

he said, `will betray you in the eyes of my father. Considerations of rank and

position will, no doubt, induce him to forsake us and sever whatever ties bind

him to this home. He will, if we fail to repress our tears, accuse us before Nasiri'd-Din

Shah, as victims of the charm of a hateful enemy. He will obtain the sovereign's

consent to our death, and will probably, with his own hands, proceed to slay us.

Why should we, who have never embraced that Cause, allow ourselves to suffer such

a fate at his hands? All we should do is to defend her against those who denounce

her as the very negation of chastity and honour. We should ever treasure her love

in our hearts and maintain in the face of a slanderous enemy the integrity of

that life.'

I wept hot tears as my son unfolded to my

eyes that tragic tale. I was so overcome with emotion that I fell prostrate and

unconscious upon the ground. When I had recovered, I found my son a prey to an

agony no less severe than my own. He lay upon his couch, weeping in a passion

of devotion. Beholding my plight, he approached and comforted me. `Your tears,'

he said, `will betray you in the eyes of my father. Considerations of rank and

position will, no doubt, induce him to forsake us and sever whatever ties bind

him to this home. He will, if we fail to repress our tears, accuse us before Nasiri'd-Din

Shah, as victims of the charm of a hateful enemy. He will obtain the sovereign's

consent to our death, and will probably, with his own hands, proceed to slay us.

Why should we, who have never embraced that Cause, allow ourselves to suffer such

a fate at his hands? All we should do is to defend her against those who denounce

her as the very negation of chastity and honour. We should ever treasure her love

in our hearts and maintain in the face of a slanderous enemy the integrity of

that life.'

"His words allayed my inner agitation. I went

to her chest and, with the key she had placed in my hand, opened it. I found a

small vial of the choicest perfume, beside which lay a rosary, a coral necklace,

and three rings, mounted with turquoise, cornelian, and ruby stones. As I gazed

upon her earthly belongings, I mused over the circumstances of her eventful life,

and recalled, with a throb of wonder, her intrepid courage, her zeal, her high

sense of duty and unquestioning devotion. I was reminded of her literary attainments,

and brooded over the imprisonments, the shame, and the calumny which she had faced

with a fortitude such as no other woman

"His words allayed my inner agitation. I went

to her chest and, with the key she had placed in my hand, opened it. I found a

small vial of the choicest perfume, beside which lay a rosary, a coral necklace,

and three rings, mounted with turquoise, cornelian, and ruby stones. As I gazed

upon her earthly belongings, I mused over the circumstances of her eventful life,

and recalled, with a throb of wonder, her intrepid courage, her zeal, her high

sense of duty and unquestioning devotion. I was reminded of her literary attainments,

and brooded over the imprisonments, the shame, and the calumny which she had faced

with a fortitude such as no other woman

628

in her land could manifest.

I pictured to myself that winsome face which now, alas, lay buried beneath a mass

of earth and stones. The memory of her passionate eloquence warmed my heart, as

I repeated to myself the words that had so often dropped from her lips. The consciousness

of the vastness of her knowledge, and her mastery of the sacred Scriptures of

Islam, flashed through my mind with a suddenness that disconcerted me. Above all,

her passionate loyalty to the Faith she had embraced, her fervour as she pleaded

its cause, the services she rendered it, the woes and tribulations she endured

for its sake, the example she had given to its followers, the impetus she had

lent to its advancement the name she had carved for herself in the hearts of her

fellow-countrymen, all these I remembered as I stood beside her chest, wondering

what could have induced so great a woman to forsake all the riches and honours

with which she had been surrounded and to identify herself with the cause of an

obscure youth from Shiraz. What could have been the secret, I thought to myself,

of the power that tore her away from her home and kindred, that sustained her

throughout her stormy career, and eventually carried her to her grave? Could that

force, I pondered, be of God? Could the hand of the Almighty have guided her destiny

and steered her course amidst the perils of her life?

"On the third day after her martyrdom,(1)

the woman whose coming she had promised arrived. I enquired her name, and, finding

it to be the same as the one Tahirih had told me, delivered into her hands the

package with which I had been entrusted. I had never before met that woman, nor

did I ever see her again."(2)

"On the third day after her martyrdom,(1)

the woman whose coming she had promised arrived. I enquired her name, and, finding

it to be the same as the one Tahirih had told me, delivered into her hands the

package with which I had been entrusted. I had never before met that woman, nor

did I ever see her again."(2)

The name of that immortal woman was Fatimih,

a name which her father had bestowed upon her. She was surnamed Umm-i-Salmih by

her family and kindred, who also designated her as Zakiyyih. She was born in the

year 1233 A.H.,(3) the very

year which witnessed the birth of Baha'u'llah. She was thirty-six years of age

when she suffered martyrdom in Tihran. May future generations be enabled to present

a

The name of that immortal woman was Fatimih,

a name which her father had bestowed upon her. She was surnamed Umm-i-Salmih by

her family and kindred, who also designated her as Zakiyyih. She was born in the

year 1233 A.H.,(3) the very

year which witnessed the birth of Baha'u'llah. She was thirty-six years of age

when she suffered martyrdom in Tihran. May future generations be enabled to present

a

629

worthy account of a life

which her contemporaries have failed adequately to recognise. May future historians

perceive the full measure of her influence, and record the unique services this

great woman has rendered to her land and its people. May the followers of the

Faith which she served so well strive to follow her example, recount her deeds,

collect her writings, unfold the secret of her talents, and establish her, for

all time, in the memory and affections of the peoples and kindreds of the earth.(1)

Another distinguished figure among the disciples

of the Bab who met his death during the turbulent time that had overwhelmed Tihran

was Siyyid Husayn-i-Yazdi, who was the Bab's amanuensis both in Mah-Ku and Chihriq.

Such was his knowledge of the teachings of the Faith that the Bab, in a Tablet

addressed to Mirza Yahya, urged the latter to seek enlightenment from him in whatever

might pertain to the sacred writings. A man of standing and experience, in whom

the Bab reposed the utmost confidence and with whom he had been intimately associated,

he suffered, after the martyrdom of his Master in Tabriz, the agony of a long

confinement in the subterranean dungeon of Tihran, which confinement terminated

in his martyrdom. To a very great

Another distinguished figure among the disciples

of the Bab who met his death during the turbulent time that had overwhelmed Tihran

was Siyyid Husayn-i-Yazdi, who was the Bab's amanuensis both in Mah-Ku and Chihriq.

Such was his knowledge of the teachings of the Faith that the Bab, in a Tablet