268

CHAPTER XV

TAHIRIH'S JOURNEY FROM KARBILA

TO KHURASAN

S THE appointed hour approached when, according to the dispensations

of Providence, the veil which still concealed the fundamental verities of the

Faith was to be rent asunder, there blazed forth in the heart of Khurasan a flame

of such consuming intensity that the most formidable obstacles standing in the

way of the ultimate recognition of the Cause melted away and vanished.(1)

That fire caused such a conflagration in the hearts of men that the effects of

its quickening power were felt in the most outlying provinces of Persia. It obliterated

every trace of the misgivings and doubts which had still lingered in the hearts

of the believers, and had hitherto hindered them from apprehending the full measure

of its glory. The decree of the enemy had condemned to perpetual isolation Him

who was the embodiment of the beauty of God, and sought thereby to quench for

all time the flame of His love. The hand of Omnipotence, however, was busily engaged,

at a time when the host of evil-doers were darkly plotting against Him, in confounding

their schemes and in nullifying their efforts. In the easternmost province of

Persia, the Almighty had, through the hand of Quddus, lit a fire that glowed with

the hottest flame in the breasts of the people of Khurasan. And in Karbila, beyond

the western confines of that land, He had kindled the light of Tahirih, a light

that was destined to shed its radiance upon the whole of Persia. From the east

S THE appointed hour approached when, according to the dispensations

of Providence, the veil which still concealed the fundamental verities of the

Faith was to be rent asunder, there blazed forth in the heart of Khurasan a flame

of such consuming intensity that the most formidable obstacles standing in the

way of the ultimate recognition of the Cause melted away and vanished.(1)

That fire caused such a conflagration in the hearts of men that the effects of

its quickening power were felt in the most outlying provinces of Persia. It obliterated

every trace of the misgivings and doubts which had still lingered in the hearts

of the believers, and had hitherto hindered them from apprehending the full measure

of its glory. The decree of the enemy had condemned to perpetual isolation Him

who was the embodiment of the beauty of God, and sought thereby to quench for

all time the flame of His love. The hand of Omnipotence, however, was busily engaged,

at a time when the host of evil-doers were darkly plotting against Him, in confounding

their schemes and in nullifying their efforts. In the easternmost province of

Persia, the Almighty had, through the hand of Quddus, lit a fire that glowed with

the hottest flame in the breasts of the people of Khurasan. And in Karbila, beyond

the western confines of that land, He had kindled the light of Tahirih, a light

that was destined to shed its radiance upon the whole of Persia. From the east

269

and from the west of that

country, the voice of the Unseen summoned those twin great lights to hasten to

the land of Ta,(1) the day-spring

of glory, the home of Baha'u'llah. He bade them each seek the presence, and revolve

round the person of that Day-Star of Truth, to seek His advice, to reinforce His

efforts, and to prepare the way for His coming Revelation.

In pursuance of the Divine

decree, in the days when Quddus was still residing in Mashhad, there was revealed

from the pen of the Bab a Tablet addressed to all the believers of Persia, in

which every loyal adherent of the Faith was enjoined to "hasten to the Land of

Kha," the province of Khurasan.(2)

The news of this high injunction spread with marvellous rapidity

and aroused universal enthusiasm. It reached the ears of Tahirih, who, at that

time, was residing in Karbila and was bending every effort to extend the scope

of the Faith she had espoused.(3)

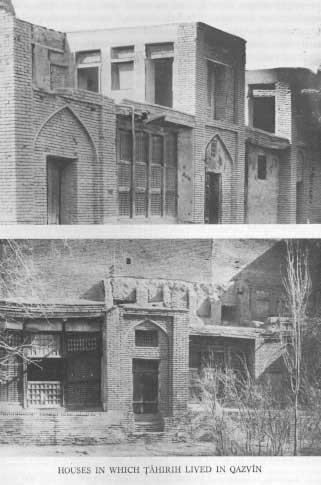

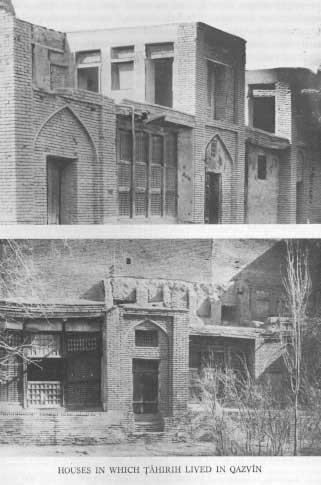

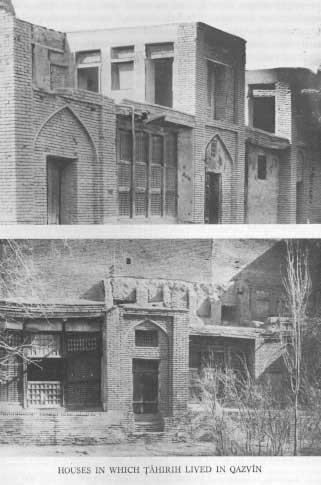

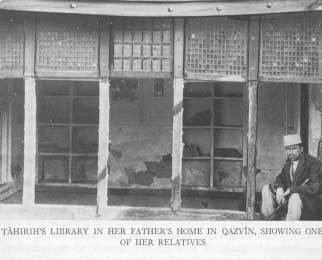

She had left her native town of Qazvin and had arrived, after the death of Siyyid

Kazim, at that holy city, in eager expectation of witnessing the signs which the

departed siyyid had foretold. In the foregoing pages we have seen how instinctively

she had been led to discover the Revelation of the Bab and how spontaneously she

had acknowledged its truth. Unwarned and uninvited, she perceived the dawning

light of the promised Revelation breaking upon the city of Shiraz, and was prompted

to pen her message and plead her fidelity to Him who was the Revealer of that

light.

In pursuance of the Divine

decree, in the days when Quddus was still residing in Mashhad, there was revealed

from the pen of the Bab a Tablet addressed to all the believers of Persia, in

which every loyal adherent of the Faith was enjoined to "hasten to the Land of

Kha," the province of Khurasan.(2)

The news of this high injunction spread with marvellous rapidity

and aroused universal enthusiasm. It reached the ears of Tahirih, who, at that

time, was residing in Karbila and was bending every effort to extend the scope

of the Faith she had espoused.(3)

She had left her native town of Qazvin and had arrived, after the death of Siyyid

Kazim, at that holy city, in eager expectation of witnessing the signs which the

departed siyyid had foretold. In the foregoing pages we have seen how instinctively

she had been led to discover the Revelation of the Bab and how spontaneously she

had acknowledged its truth. Unwarned and uninvited, she perceived the dawning

light of the promised Revelation breaking upon the city of Shiraz, and was prompted

to pen her message and plead her fidelity to Him who was the Revealer of that

light.

The Bab's immediate response

to her declaration of faith which, without attaining His presence, she was moved

to make, animated her zeal and vastly increased her courage. She arose to spread

abroad His teachings, vehemently denounced the corruption and perversity of her

generation, and fearlessly advocated a fundamental revolution in the habits

The Bab's immediate response

to her declaration of faith which, without attaining His presence, she was moved

to make, animated her zeal and vastly increased her courage. She arose to spread

abroad His teachings, vehemently denounced the corruption and perversity of her

generation, and fearlessly advocated a fundamental revolution in the habits

270

and manners of her people.(1)

Her indomitable spirit was quickened by the fire of her love for the Bab, and

the glory of her vision was further enhanced by the discovery of the inestimable

blessings latent in His Revelation. The innate fearlessness and the strength of

her character were reinforced a hundredfold by her immovable conviction of the

ultimate victory of the Cause she had embraced; and her boundless energy was revitalised

by her recognition of the abiding value of the Mission she had risen to champion.

All who met her in Karbila were ensnared by her bewitching eloquence

and felt the fascination of her words. None could resist her charm; few could

escape the contagion of her belief. All testified to the extraordinary traits

of her character, marvelled at her amazing personality, and were convinced of

the sincerity of her convictions.

She was able to win to the Cause the revered

widow of Siyyid Kazim, who was born in Shiraz, and was the first among the women

of Karbila to recognise its truth. I have heard Shaykh Sultan describe her extreme

devotion to Tahirih, whom she revered as her spiritual guide and esteemed as her

affectionate companion. He was also a fervent admirer of the character of the

widow of the Siyyid, to whose gentleness of manner he often paid a glowing tribute.

"Such was her attachment to Tahirih," Shaykh Sultan was often heard to remark,

"that she was extremely reluctant to allow that heroine who was a guest in her

house to absent herself, though it were for an hour, from her presence. So great

an attachment on her part did not fail to excite the curiosity and quicken the

faith of her women friends, both Persian and Arab, who were constant visitors

in her home. In the first year of her acceptance of the Message, she suddenly

She was able to win to the Cause the revered

widow of Siyyid Kazim, who was born in Shiraz, and was the first among the women

of Karbila to recognise its truth. I have heard Shaykh Sultan describe her extreme

devotion to Tahirih, whom she revered as her spiritual guide and esteemed as her

affectionate companion. He was also a fervent admirer of the character of the

widow of the Siyyid, to whose gentleness of manner he often paid a glowing tribute.

"Such was her attachment to Tahirih," Shaykh Sultan was often heard to remark,

"that she was extremely reluctant to allow that heroine who was a guest in her

house to absent herself, though it were for an hour, from her presence. So great

an attachment on her part did not fail to excite the curiosity and quicken the

faith of her women friends, both Persian and Arab, who were constant visitors

in her home. In the first year of her acceptance of the Message, she suddenly

271

fell ill, and after the lapse

of three days, as had been the case with Siyyid Kazim, she departed this life."

Among the men who in Karbila eagerly embraced,

through the efforts of Tahirih, the Cause of the Bab, was a certain Shaykh Salih,

an Arab resident of that city who was the first to shed his blood in the path

of the Faith, in Tihran. She was so profuse in her praise of Shaykh Salih that

a few suspected him of being equal in rank to Quddus. Shaykh Sultan was also among

those who fell under the spell of Tahirih. On his return from Shiraz, he identified

himself with the Faith, boldly and assiduously promoted its interests, and did

his utmost to execute her instructions and wishes. Another admirer

was Shaykh Muhammad-i-Shibl, the father of Muhammad-Mustafa, an Arab native of

Baghdad who ranked high among the ulamas of that city. By the aid of this chosen

band of staunch and able supporters, Tahirih was able to fire the imagination

and to enlist the allegiance of a considerable number of the Persian and Arab

inhabitants of Iraq, most of whom were led by her to join forces with those of

their brethren in Persia who were soon to be called upon to shape by their deeds

the destiny, and to seal with their life-blood the triumph, of the Cause of God.

Among the men who in Karbila eagerly embraced,

through the efforts of Tahirih, the Cause of the Bab, was a certain Shaykh Salih,

an Arab resident of that city who was the first to shed his blood in the path

of the Faith, in Tihran. She was so profuse in her praise of Shaykh Salih that

a few suspected him of being equal in rank to Quddus. Shaykh Sultan was also among

those who fell under the spell of Tahirih. On his return from Shiraz, he identified

himself with the Faith, boldly and assiduously promoted its interests, and did

his utmost to execute her instructions and wishes. Another admirer

was Shaykh Muhammad-i-Shibl, the father of Muhammad-Mustafa, an Arab native of

Baghdad who ranked high among the ulamas of that city. By the aid of this chosen

band of staunch and able supporters, Tahirih was able to fire the imagination

and to enlist the allegiance of a considerable number of the Persian and Arab

inhabitants of Iraq, most of whom were led by her to join forces with those of

their brethren in Persia who were soon to be called upon to shape by their deeds

the destiny, and to seal with their life-blood the triumph, of the Cause of God.

The Bab's appeal, which was originally addressed

to His followers in Persia, was soon transmitted to the adherents of His Faith

in Iraq. Tahirih gloriously responded. Her example was followed immediately by

a large number of her faithful admirers, all of whom expressed their readiness

to journey forthwith to Khurasan. The ulamas of Karbila sought to dissuade her

from undertaking that journey. Perceiving immediately the motive which prompted

them to tender her such advice, and aware of their malignant design, she addressed

to each of these sophists a lengthy epistle in which she set forth her motives

and exposed their dissimulation.(1)

The Bab's appeal, which was originally addressed

to His followers in Persia, was soon transmitted to the adherents of His Faith

in Iraq. Tahirih gloriously responded. Her example was followed immediately by

a large number of her faithful admirers, all of whom expressed their readiness

to journey forthwith to Khurasan. The ulamas of Karbila sought to dissuade her

from undertaking that journey. Perceiving immediately the motive which prompted

them to tender her such advice, and aware of their malignant design, she addressed

to each of these sophists a lengthy epistle in which she set forth her motives

and exposed their dissimulation.(1)

272

From Karbila she proceeded to Baghdad.(1)

A representative delegation, consisting of the ablest leaders among the shi'ah,

the sunni, the Christian and Jewish communities of that city, sought her presence

and endeavoured to convince her of the folly of her actions. She was able, however,

to silence their protestations, and astounded them with the force of her argument.

Disillusioned and confused, they retired, deeply conscious of their own impotence.(2)

From Karbila she proceeded to Baghdad.(1)

A representative delegation, consisting of the ablest leaders among the shi'ah,

the sunni, the Christian and Jewish communities of that city, sought her presence

and endeavoured to convince her of the folly of her actions. She was able, however,

to silence their protestations, and astounded them with the force of her argument.

Disillusioned and confused, they retired, deeply conscious of their own impotence.(2)

The ulamas of Kirmanshah respectfully

received her and presented her with various tokens of their esteem and admiration.(3)

In Hamadan,(4) however, the

ecclesiastical leaders

The ulamas of Kirmanshah respectfully

received her and presented her with various tokens of their esteem and admiration.(3)

In Hamadan,(4) however, the

ecclesiastical leaders

273

of the city were divided

in their attitude towards her. A few sought privily to provoke the people and

undermine her prestige; others were moved to extol openly her virtues and applaud

her courage. "It behoves us," these friends declared from their pulpits, "to follow

her noble example and reverently to ask her to unravel for us the mysteries of

the Qur'an and to resolve the intricacies of the holy Book. For our highest attainments

are but a drop compared to the immensity of her knowledge." While in Hamadan,

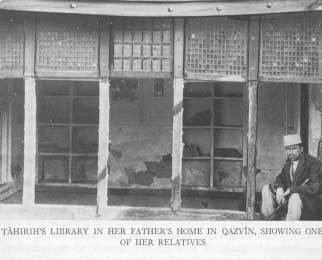

Tahirih was met by those whom her father, Haji Mulla Salih, had sent from Qazvin

to welcome and urge her, on his behalf, to visit her native town and prolong her

stay in their midst.(1) She

reluctantly consented. Ere she departed, she bade those who had accompanied her

from Iraq to proceed to their native land. Among them were Shaykh Sultan, Shaykh

Muhammad-i-Shibl and his youthful son, Muhammad-Mustafa, Abid and his son Nasir,

who subsequently was given the name of Haji Abbas. Those of her companions who

had been living in Persia, such as Siyyid Muhammad-i-Gulpaygani, whose pen-name

was Ta'ir, and whom Tahirih had styled Fata'l-Malih, and others were also bidden

to return to their homes. Only two of her companions remained with her--Shaykh

Salih and Mulla Ibrahim-i-Gulpaygani, both of whom quaffed the cup of martyrdom,

the first in Tihran and the other in Qazvin. Of her own kinsmen, Mirza Muhammad-'Ali,

one of the Letters of the Living and her brother-in-law, and Siyyid Abdu'l-Hadi,

who had been betrothed to her daughter, travelled with her all the way from Karbila

to Qazvin.

On her arrival at the house

of her father, her cousin, the haughty and false-hearted Mulla Muhammad, son of

Mulla Taqi, who esteemed himself, next to his father and his uncle, the most accomplished

of all the mujtahids of Persia, sent certain ladies of his own household to persuade

Tahirih to transfer her residence from her father's house to his own. "Say to

my presumptuous and arrogant kinsman," was her bold reply to the messengers: "`If

your desire had really been to be a faithful mate and companion to me, you would

have hastened to meet me in Karbila and would on foot have

On her arrival at the house

of her father, her cousin, the haughty and false-hearted Mulla Muhammad, son of

Mulla Taqi, who esteemed himself, next to his father and his uncle, the most accomplished

of all the mujtahids of Persia, sent certain ladies of his own household to persuade

Tahirih to transfer her residence from her father's house to his own. "Say to

my presumptuous and arrogant kinsman," was her bold reply to the messengers: "`If

your desire had really been to be a faithful mate and companion to me, you would

have hastened to meet me in Karbila and would on foot have

274

275

guided my howdah(1)

all the way to Qazvin. I would, while journeying with you, have aroused you from

your sleep of heedlessness and would have shown you the way of truth. But this

was not to be. Three years have elapsed since our separation. Neither in this

world nor in the next can I ever be associated with you. I have cast you out of

my life for ever.'"

guided my howdah(1)

all the way to Qazvin. I would, while journeying with you, have aroused you from

your sleep of heedlessness and would have shown you the way of truth. But this

was not to be. Three years have elapsed since our separation. Neither in this

world nor in the next can I ever be associated with you. I have cast you out of

my life for ever.'"

So stern and unyielding a reply roused both

Mulla Muhammad and his father to a burst of fury. They immediately pronounced

her a heretic, and strove day and night to undermine her position and to sully

her fame. Tahirih vehemently defended herself and persisted in exposing the depravity

of their character.(2) Her father,

a peace-loving and fair-minded

So stern and unyielding a reply roused both

Mulla Muhammad and his father to a burst of fury. They immediately pronounced

her a heretic, and strove day and night to undermine her position and to sully

her fame. Tahirih vehemently defended herself and persisted in exposing the depravity

of their character.(2) Her father,

a peace-loving and fair-minded

276

man, deplored this acrimonious

dispute and endeavoured to bring about a reconciliation and harmony between them,

but failed in his efforts.

This state of tension continued

until the time when a certain Mulla Abdu'llah, a native of Shiraz and fervent

admirer of both Shaykh Ahmad and Siyyid Kazim, arrived in Qazvin at the beginning

of the month of Ramadan, in the year 1263 A.H.(1)

Subsequently, in the course of his trial in Tihran, in the presence of the Sahib-Divan,

this same Mulla Abdu'llah recounted the following: "I have never been a convinced

Babi. When I arrived at Qazvin, I was on my way to Mah-Ku, intending to visit

the Bab and investigate the nature of His Cause. On the day of my arrival at Qazvin,

I became aware that the town was in a great state of turmoil. As I was passing

through the market-place, I saw a crowd of ruffians who had stripped a man of

his head-dress and shoes, had wound his turban around his neck, and by it were

dragging him through the streets. An angry multitude was tormenting him with their

threats, their blows and curses. `His unpardonable guilt,' I was told in answer

to my enquiry, `is that he has dared to extol in public the virtues of Shaykh

Ahmad and Siyyid Kazim. Accordingly, Haji Mulla Taqi, the Hujjatu'l-Islam, has

pronounced him a heretic and decreed his expulsion from the town.'"

This state of tension continued

until the time when a certain Mulla Abdu'llah, a native of Shiraz and fervent

admirer of both Shaykh Ahmad and Siyyid Kazim, arrived in Qazvin at the beginning

of the month of Ramadan, in the year 1263 A.H.(1)

Subsequently, in the course of his trial in Tihran, in the presence of the Sahib-Divan,

this same Mulla Abdu'llah recounted the following: "I have never been a convinced

Babi. When I arrived at Qazvin, I was on my way to Mah-Ku, intending to visit

the Bab and investigate the nature of His Cause. On the day of my arrival at Qazvin,

I became aware that the town was in a great state of turmoil. As I was passing

through the market-place, I saw a crowd of ruffians who had stripped a man of

his head-dress and shoes, had wound his turban around his neck, and by it were

dragging him through the streets. An angry multitude was tormenting him with their

threats, their blows and curses. `His unpardonable guilt,' I was told in answer

to my enquiry, `is that he has dared to extol in public the virtues of Shaykh

Ahmad and Siyyid Kazim. Accordingly, Haji Mulla Taqi, the Hujjatu'l-Islam, has

pronounced him a heretic and decreed his expulsion from the town.'"

I was amazed at the explanation given me.

How could a shaykhi, I thought to myself, be regarded as a heretic and be deemed

worthy of such cruel treatment? Desirous of ascertaining from Mulla Taqi himself

the truth of this report, I betook myself to his school and asked whether he had

actually pronounced such a condemnation against him. `Yes,' he bluntly replied,

`the god whom the late Shaykh Ahmad-i-Bahrayni worshipped is a god in whom I can

never believe. Him as well as his followers I regard as the very embodiments of

error.' I was moved that very moment to smite his face in the presence of his

assembled disciples. I restrained myself, however, and vowed that, God willing,

I would pierce his lips with my spear so that he would never be again able to

utter such blasphemy.

I was amazed at the explanation given me.

How could a shaykhi, I thought to myself, be regarded as a heretic and be deemed

worthy of such cruel treatment? Desirous of ascertaining from Mulla Taqi himself

the truth of this report, I betook myself to his school and asked whether he had

actually pronounced such a condemnation against him. `Yes,' he bluntly replied,

`the god whom the late Shaykh Ahmad-i-Bahrayni worshipped is a god in whom I can

never believe. Him as well as his followers I regard as the very embodiments of

error.' I was moved that very moment to smite his face in the presence of his

assembled disciples. I restrained myself, however, and vowed that, God willing,

I would pierce his lips with my spear so that he would never be again able to

utter such blasphemy.

"I straightway left his presence and directed

my steps

"I straightway left his presence and directed

my steps

277

towards the market, where

I bought a dagger and a spear-head of the sharpest and finest steel. I concealed

them in my bosom, ready to gratify the passion that burned within me. I was waiting

for my opportunity when, one night, I entered the masjid in which he was wont

to lead the congregation in prayer. I waited until the hour of dawn, at which

time I saw an old woman enter the masjid, carrying with her a rug, which she spread

over the floor of the mihrab.(1)

Soon after, I saw Mulla Taqi enter alone, walk to the mihrab, and offer his prayer.

Cautiously and quietly, I followed him and stood behind him. He was prostrating

himself on the floor, when I rushed upon him, drew out my spear-head, and plunged

it into the back of his neck. He uttered a loud cry. I threw him on his back and,

unsheathing my dagger, drove it hilt-deep into his mouth. With the same dagger,

I struck him at several places in his breast and side, and left him bleeding in

the mihrab.

"I ascended immediately the roof of the masjid

and watched the frenzy and agitation of the multitude. A crowd rushed in and,

placing him upon a litter, transported him to his house. Unable to identify the

murderer, the people seized the occasion to gratify their basest instincts. They

rushed at one another's throats, violently attacked and mutually accused one another

in the presence of the governor. Finding out that a large number of innocent people

had been gravely molested and thrown into prison, I was impelled by the voice

of my conscience to confess my act. I accordingly besought the presence of the

governor and said to him: `If I deliver into your hands the author of this murder,

will you promise me to set free all the innocent people who are suffering his

place?' No sooner had I obtained from him the necessary assurance than I confessed

to him that I had committed the deed. He was not disposed at first to believe

me. At my request, he summoned the old woman who had spread the rug in the mihrab,

but refused to be convinced by the evidence which she gave. I was finally conducted

to the bedside of Mulla Taqi, who was on the point of death. As soon as he saw

me, he recognised my features. In his agitation, he pointed with his finger to

"I ascended immediately the roof of the masjid

and watched the frenzy and agitation of the multitude. A crowd rushed in and,

placing him upon a litter, transported him to his house. Unable to identify the

murderer, the people seized the occasion to gratify their basest instincts. They

rushed at one another's throats, violently attacked and mutually accused one another

in the presence of the governor. Finding out that a large number of innocent people

had been gravely molested and thrown into prison, I was impelled by the voice

of my conscience to confess my act. I accordingly besought the presence of the

governor and said to him: `If I deliver into your hands the author of this murder,

will you promise me to set free all the innocent people who are suffering his

place?' No sooner had I obtained from him the necessary assurance than I confessed

to him that I had committed the deed. He was not disposed at first to believe

me. At my request, he summoned the old woman who had spread the rug in the mihrab,

but refused to be convinced by the evidence which she gave. I was finally conducted

to the bedside of Mulla Taqi, who was on the point of death. As soon as he saw

me, he recognised my features. In his agitation, he pointed with his finger to

278

me, indicating that I had

attacked him. He signified his desire that I be taken away from his presence.

Shortly after, he expired. I was immediately arrested, was convicted of murder,

and thrown into prison. The governor, however, failed to keep his promise and

refused to release the prisoners."

The candour and sincerity of Mulla Abdu'llah

greatly pleased the Sahib-Divan. He gave secret orders to his attendants to enable

him to escape from prison. At the hour of midnight, the prisoner took refuge in

the home of Rida Khan-i-Sardar, who had recently been married to the sister of

the Sipah-Salar, and remained concealed in that house until the great struggle

or Shaykh Tabarsi, when he determined to throw in his lot with the heroic defenders

of the fort. He, as well as Rida Khan, who followed him to Mazindaran, quaffed

eventually the cup of martyrdom.

The candour and sincerity of Mulla Abdu'llah

greatly pleased the Sahib-Divan. He gave secret orders to his attendants to enable

him to escape from prison. At the hour of midnight, the prisoner took refuge in

the home of Rida Khan-i-Sardar, who had recently been married to the sister of

the Sipah-Salar, and remained concealed in that house until the great struggle

or Shaykh Tabarsi, when he determined to throw in his lot with the heroic defenders

of the fort. He, as well as Rida Khan, who followed him to Mazindaran, quaffed

eventually the cup of martyrdom.

The circumstances of the murder

fanned to fury the wrath of the lawful heirs of Mulla Taqi, who now determined

to wreak their vengeance upon Tahirih. They succeeded in having her placed in

the strictest confinement in the house of her father, and charged those women

whom they had selected to watch over her, not to allow their captive to leave

her room except for the purpose of performing her daily ablutions. They accused

her of really being the instigator of the crime. "No one else but you," they asserted,

"is guilty of the murder of our father. You issued the order for his assassination."

Those whom they had arrested and confined were conducted by them to Tihran and

were incarcerated in the home of one of the kad-khudas(1) of the capital. The

friends and heirs of Mulla Taqi scattered themselves in all directions, denouncing

their captives as the repudiators of the law of Islam and demanding that they

be immediately put to death.

The circumstances of the murder

fanned to fury the wrath of the lawful heirs of Mulla Taqi, who now determined

to wreak their vengeance upon Tahirih. They succeeded in having her placed in

the strictest confinement in the house of her father, and charged those women

whom they had selected to watch over her, not to allow their captive to leave

her room except for the purpose of performing her daily ablutions. They accused

her of really being the instigator of the crime. "No one else but you," they asserted,

"is guilty of the murder of our father. You issued the order for his assassination."

Those whom they had arrested and confined were conducted by them to Tihran and

were incarcerated in the home of one of the kad-khudas(1) of the capital. The

friends and heirs of Mulla Taqi scattered themselves in all directions, denouncing

their captives as the repudiators of the law of Islam and demanding that they

be immediately put to death.

Baha'u'llah who was at that time residing

in Tihran, was informed of the plight of these prisoners who had been the companions

and supporters of Tahirih. As He was already acquainted with the kad-khuda in

whose home they were incarcerated, He decided to visit them and intervene in their

behalf. That avaricious and deceitful official, who was fully aware of the extreme

generosity of Baha'u'llah, greatly exaggerated

Baha'u'llah who was at that time residing

in Tihran, was informed of the plight of these prisoners who had been the companions

and supporters of Tahirih. As He was already acquainted with the kad-khuda in

whose home they were incarcerated, He decided to visit them and intervene in their

behalf. That avaricious and deceitful official, who was fully aware of the extreme

generosity of Baha'u'llah, greatly exaggerated

279

in the hope of deriving a

substantial pecuniary advantage for himself, the misfortune that had befallen

the unhappy captives. "They are destitute of the barest necessities of life,"

urged the kad-khuda. "They hunger for food, and their clothing is wretchedly scanty."

Baha'u'llah extended immediate financial assistance for their relief, and urged

the kad-khuda to relax the severity of the rule under which they were confined.

The latter consented to relieve a few who were unable to support the oppressive

weight of their chains, and for the rest did whatever he could to alleviate the

rigour of their confinement. Prompted by greed, he informed his superiors of the

situation, and emphasised the fact that both food and money were being regularly

supplied by Baha'u'llah for those who were imprisoned in his house.

These officials were in their turn tempted

to derive every possible advantage from the liberality of Baha'u'llah. They summoned

Him to their presence, protested against His action, and accused Him of complicity

in the act for which the captives had been condemned. "The kad-khuda," replied

Baha'u'llah, "pleaded their cause before Me and enlarged upon their sufferings

and needs. He himself bore witness to their innocence and appealed to Me for help.

In return for the aid which, in response to his invitation, I was impelled to

extend, you now charge Me with a crime of which I am innocent." Hoping to intimidate

Baha'u'llah by threatening immediate punishment, they refused to allow Him to

return to His home. The confinement to which He was subjected was the first affliction

that befell Baha'u'llah in the path of the Cause of God; the first imprisonment

He suffered for the sake of His loved ones. He remained in captivity for a few

days, until Ja'far-Quli Khan, the brother of Mirza Aqa Khan-i-Nuri, who at a later

time was appointed Grand Vazir of the Shah, and a number of other friends intervened

in His behalf and, threatening the kad-khuda in severe a language, were able to

effect His release. Those who had been responsible for His confinement had confidently

hoped to receive, in return for His deliverance, the sum of one thousand tumans,(1)

but they soon found out that they were forced to comply with the wishes of Ja'far-Quli

Khan without

These officials were in their turn tempted

to derive every possible advantage from the liberality of Baha'u'llah. They summoned

Him to their presence, protested against His action, and accused Him of complicity

in the act for which the captives had been condemned. "The kad-khuda," replied

Baha'u'llah, "pleaded their cause before Me and enlarged upon their sufferings

and needs. He himself bore witness to their innocence and appealed to Me for help.

In return for the aid which, in response to his invitation, I was impelled to

extend, you now charge Me with a crime of which I am innocent." Hoping to intimidate

Baha'u'llah by threatening immediate punishment, they refused to allow Him to

return to His home. The confinement to which He was subjected was the first affliction

that befell Baha'u'llah in the path of the Cause of God; the first imprisonment

He suffered for the sake of His loved ones. He remained in captivity for a few

days, until Ja'far-Quli Khan, the brother of Mirza Aqa Khan-i-Nuri, who at a later

time was appointed Grand Vazir of the Shah, and a number of other friends intervened

in His behalf and, threatening the kad-khuda in severe a language, were able to

effect His release. Those who had been responsible for His confinement had confidently

hoped to receive, in return for His deliverance, the sum of one thousand tumans,(1)

but they soon found out that they were forced to comply with the wishes of Ja'far-Quli

Khan without

280

the hope of receiving, either

from him or from Baha'u'llah, the slightest reward. With profuse apologies and

with the utmost regret, they surrendered their Captive into his hands.

The heirs of Mulla Taqi were

in the meantime bending every effort to avenge the blood of their distinguished

kinsman. Unsatisfied with what they had already accomplished, they directed their

appeal to Muhammad Shah himself, and endeavoured to win his sympathy to their

cause. The Shah is reported to have returned this answer: "Your father, Mulla

Taqi, surely could not have claimed to be superior to the Imam Ali, the Commander

of the Faithful. Did not the latter instruct his disciples that, should he fall

a victim to the sword of Ibn-i-Muljam, the murderer alone should, by his death,

be made to atone for his act, that no one else but he should be put to death?

Why should not the murder of your father be similarly avenged? Declare to me his

murderer, and I will issue my orders that he be delivered into your hands in order

that you may inflict upon him the punishment which he deserves."

The heirs of Mulla Taqi were

in the meantime bending every effort to avenge the blood of their distinguished

kinsman. Unsatisfied with what they had already accomplished, they directed their

appeal to Muhammad Shah himself, and endeavoured to win his sympathy to their

cause. The Shah is reported to have returned this answer: "Your father, Mulla

Taqi, surely could not have claimed to be superior to the Imam Ali, the Commander

of the Faithful. Did not the latter instruct his disciples that, should he fall

a victim to the sword of Ibn-i-Muljam, the murderer alone should, by his death,

be made to atone for his act, that no one else but he should be put to death?

Why should not the murder of your father be similarly avenged? Declare to me his

murderer, and I will issue my orders that he be delivered into your hands in order

that you may inflict upon him the punishment which he deserves."

The uncompromising attitude

of the Shah induced them to abandon the hopes which they had cherished. They declared

Shaykh Salih to be the murderer of their father, obtained his arrest, and ignominiously

put him to death. He was the first to shed his blood on Persian soil in the path

of the Cause of God; the first of that glorious company destined to seal with

their life-blood the triumph of God's holy Faith. As he was being conducted to

the scene of his martyrdom, his face glowed with zeal and joy. He hastened to

the foot of the gallows and met his executioner as if he were welcoming a dear

and lifelong friend. Words of triumph and hope fell unceasingly from his lips.

"I discarded," he cried, with exultation, as his end approached, "the hopes and

the beliefs of men from the moment I recognised Thee, Thou who art my Hope and

my Belief!" His remains were interred in the courtyard of the shrine of the Imam-Zadih

Zayd in Tihran.

The uncompromising attitude

of the Shah induced them to abandon the hopes which they had cherished. They declared

Shaykh Salih to be the murderer of their father, obtained his arrest, and ignominiously

put him to death. He was the first to shed his blood on Persian soil in the path

of the Cause of God; the first of that glorious company destined to seal with

their life-blood the triumph of God's holy Faith. As he was being conducted to

the scene of his martyrdom, his face glowed with zeal and joy. He hastened to

the foot of the gallows and met his executioner as if he were welcoming a dear

and lifelong friend. Words of triumph and hope fell unceasingly from his lips.

"I discarded," he cried, with exultation, as his end approached, "the hopes and

the beliefs of men from the moment I recognised Thee, Thou who art my Hope and

my Belief!" His remains were interred in the courtyard of the shrine of the Imam-Zadih

Zayd in Tihran.

The unsatiable hatred that

animated those who had been responsible for the martyrdom of Shaykh Salih impelled

them to seek additional instruments for the furtherance of their designs. Haji

Mirza Aqasi, whom the Sahib-Divan had succeeded in convincing of the treacherous

conduct of the heirs

The unsatiable hatred that

animated those who had been responsible for the martyrdom of Shaykh Salih impelled

them to seek additional instruments for the furtherance of their designs. Haji

Mirza Aqasi, whom the Sahib-Divan had succeeded in convincing of the treacherous

conduct of the heirs

281

of Mulla Taqi, refused to

entertain their appeal. Undeterred by his refusal, they submitted their case to

the Sadr-i-Ardibili, a man notoriously presumptuous and one of the most arrogant

among the ecclesiastical leaders of Persia. "Behold," they pleaded, "the indignity

that has been inflicted upon those whose supreme function it is to keep guard

over the integrity of the Law. How can you, who are its chief and illustrious

exponent, allow so grave an affront to its dignity to remain unpunished? Are you

really incapable of avenging the blood of that slaughtered minister of the Prophet

of God? Do you not realise that to tolerate such a heinous crime would in itself

unloose a flood of calumny against those who are the chief repositories of the

teachings and principles of our Faith? Will not your silence embolden the enemies

of Islam to shatter the structure which your own hands have reared? As a result,

will not your own life be endangered?"

The Sadr-i-Ardibili was sore afraid, and in

his impotence sought to beguile his sovereign. He addressed the following request

to Muhammad Shah: "I would humbly implore your Majesty to allow the captives to

accompany the heirs of that martyred leader on their return to Qazvin, that these

may, of their own accord, forgive them publicly their action, and enable them

to recover their freedom. Such a gesture on their part will considerably enhance

their position and will win them the esteem of their countrymen." The Shah, wholly

unaware of the mischievous designs of that crafty plotter, immediately granted

his request, on the express condition that a written statement be sent to him

from Qazvin assuring him that the condition of the prisoners after their freedom

was entirely satisfactory, and that no harm was likely to befall them in the future.

The Sadr-i-Ardibili was sore afraid, and in

his impotence sought to beguile his sovereign. He addressed the following request

to Muhammad Shah: "I would humbly implore your Majesty to allow the captives to

accompany the heirs of that martyred leader on their return to Qazvin, that these

may, of their own accord, forgive them publicly their action, and enable them

to recover their freedom. Such a gesture on their part will considerably enhance

their position and will win them the esteem of their countrymen." The Shah, wholly

unaware of the mischievous designs of that crafty plotter, immediately granted

his request, on the express condition that a written statement be sent to him

from Qazvin assuring him that the condition of the prisoners after their freedom

was entirely satisfactory, and that no harm was likely to befall them in the future.

No sooner were the captives delivered into

the hands of the mischief-makers than they set about gratifying their feelings

of implacable hatred towards them. On the first night after they had been handed

over to their enemies, Haji Asadu'llah, the brother of Haji Allah-Vardi and paternal

uncle of Muhammad-Hadi and Muhammad-Javad-i-Farhadi, a noted merchant of Qazvin

who had acquired a reputation for piety and uprightness which stood as high as

that of his illustrious brother, was mercilessly put to death. Knowing

No sooner were the captives delivered into

the hands of the mischief-makers than they set about gratifying their feelings

of implacable hatred towards them. On the first night after they had been handed

over to their enemies, Haji Asadu'llah, the brother of Haji Allah-Vardi and paternal

uncle of Muhammad-Hadi and Muhammad-Javad-i-Farhadi, a noted merchant of Qazvin

who had acquired a reputation for piety and uprightness which stood as high as

that of his illustrious brother, was mercilessly put to death. Knowing

282

full well that in his own

native town they would be unable to inflict upon him the punishment they desired,

they determined to take his life whilst in Tihran in a manner that would protect

them from the suspicion of murder. At the hour of midnight, they perpetrated the

shameful act, and, the next morning, announced that illness had been the cause

of his death. His friends and acquaintances, mostly natives of Qazvin, none of

whom had been able to detect the crime that had extinguished such a noble life,

accorded him a burial that befitted his station.

The rest of his companions,

among whom were Mulla Tahir-i-Shirazi and Mulla Ibrahim-i-Mahallati, both of whom

were greatly esteemed for their learning and character, were savagely put to death

immediately after their arrival at Qazvin. The entire population, which had been

sedulously instigated beforehand, clamoured for their immediate execution. A band

of shameless scoundrels, armed with knives, swords, spears, and axes, fell upon

them and tore them to pieces. They mutilated their bodies with such wanton barbarity

that no fragment of their scattered members could be found for burial.

The rest of his companions,

among whom were Mulla Tahir-i-Shirazi and Mulla Ibrahim-i-Mahallati, both of whom

were greatly esteemed for their learning and character, were savagely put to death

immediately after their arrival at Qazvin. The entire population, which had been

sedulously instigated beforehand, clamoured for their immediate execution. A band

of shameless scoundrels, armed with knives, swords, spears, and axes, fell upon

them and tore them to pieces. They mutilated their bodies with such wanton barbarity

that no fragment of their scattered members could be found for burial.

Gracious God! Acts of such incredible savagery

have been perpetrated in a town like Qazvin, which prides itself on the fact that

no less than a hundred of the highest ecclesiastical leaders of Islam dwell within

its gates, and yet none could be found among all its inhabitants to raise his

voice in protest against such revolting murders! No one seemed to question their

right to perpetrate such iniquitous and shameless deeds. No one seemed to be aware

of the utter incompatibility between such ferocious deeds committed by those who

claimed to be the sole repositories of the mysteries of Islam, and the exemplary

conduct of those who first manifested its light to the world. No one was moved

to exclaim indignantly: "O evil and perverse generation! To what depths of infamy

and shame you have sunk! Have not the abominations which you have wrought surpassed

in their ruthlessness the acts of the basest of men? Will you not recognise that

neither the beasts of the field nor any moving thing on earth has ever equalled

the ferociousness of your acts? How long is your heedlessness to last? Is it not

your

Gracious God! Acts of such incredible savagery

have been perpetrated in a town like Qazvin, which prides itself on the fact that

no less than a hundred of the highest ecclesiastical leaders of Islam dwell within

its gates, and yet none could be found among all its inhabitants to raise his

voice in protest against such revolting murders! No one seemed to question their

right to perpetrate such iniquitous and shameless deeds. No one seemed to be aware

of the utter incompatibility between such ferocious deeds committed by those who

claimed to be the sole repositories of the mysteries of Islam, and the exemplary

conduct of those who first manifested its light to the world. No one was moved

to exclaim indignantly: "O evil and perverse generation! To what depths of infamy

and shame you have sunk! Have not the abominations which you have wrought surpassed

in their ruthlessness the acts of the basest of men? Will you not recognise that

neither the beasts of the field nor any moving thing on earth has ever equalled

the ferociousness of your acts? How long is your heedlessness to last? Is it not

your

283

belief that the efficacy

of every congregational prayer is dependent upon the integrity of him who leads

that prayer? Have you not again and again declared that no such prayer is acceptable

in the sight of God until and unless the imam who leads the congregation has purged

his heart from every trace of malice? And yet you deem those who instigate and

share in the performance of such atrocities to be the true leaders of your Faith,

the very embodiments of fairness and justice. Have you not committed to their

hands the reins of your Cause and regarded them as the masters of your destinies?"

The news of this outrage

reached Tihran and spread with bewildering rapidity throughout the city. Haji

Mirza Aqasi vehemently protested. "In what passage of the Qur'an," he is reported

to have exclaimed, "in which tradition of Muhammad, has the massacre of a number

of people been justified in order to avenge the murder of a single person?" Muhammad

Shah also expressed his strong disapproval of the treacherous conduct of the Sadr-i-Ardibili

and his confederates. He denounced his cowardice, banished him from the capital,

and condemned him to a life of obscurity in Qum. His degradation from office pleased

immensely the Grand Vazir, who had hitherto laboured in vain to bring about his

downfall, and whom his sudden removal from Tihran relieved of the apprehensions

which the extension of his authority had inspired. His own denunciation of the

massacre of Qazvin was prompted, not so much by his sympathy with the Cause of

the defenceless victims, as by his hope of involving the Sadr-i-Ardibili in such

embarrassments as would inevitably disgrace him in the eyes of his sovereign.

The news of this outrage

reached Tihran and spread with bewildering rapidity throughout the city. Haji

Mirza Aqasi vehemently protested. "In what passage of the Qur'an," he is reported

to have exclaimed, "in which tradition of Muhammad, has the massacre of a number

of people been justified in order to avenge the murder of a single person?" Muhammad

Shah also expressed his strong disapproval of the treacherous conduct of the Sadr-i-Ardibili

and his confederates. He denounced his cowardice, banished him from the capital,

and condemned him to a life of obscurity in Qum. His degradation from office pleased

immensely the Grand Vazir, who had hitherto laboured in vain to bring about his

downfall, and whom his sudden removal from Tihran relieved of the apprehensions

which the extension of his authority had inspired. His own denunciation of the

massacre of Qazvin was prompted, not so much by his sympathy with the Cause of

the defenceless victims, as by his hope of involving the Sadr-i-Ardibili in such

embarrassments as would inevitably disgrace him in the eyes of his sovereign.

The failure of the Shah and of his government

to inflict immediate punishment upon the malefactors encouraged them to seek further

means for the gratification of their relentless hatred towards their opponents.

They now directed their attention to Tahirih herself, and resolved that she should

suffer at their hands the same fate that had befallen her companions. While still

in confinement, Tahirih, as soon as she was informed of the designs of her enemies,

addressed the following message to Mulla Muhammad, who had succeeded to the position

of his father and was now recognised

The failure of the Shah and of his government

to inflict immediate punishment upon the malefactors encouraged them to seek further

means for the gratification of their relentless hatred towards their opponents.

They now directed their attention to Tahirih herself, and resolved that she should

suffer at their hands the same fate that had befallen her companions. While still

in confinement, Tahirih, as soon as she was informed of the designs of her enemies,

addressed the following message to Mulla Muhammad, who had succeeded to the position

of his father and was now recognised

284

as the Imam-Jum'ih of Qazvin:

"`Fain would they put out God's light with their mouths: but God only desireth

to perfect His light, albeit the infidels abhor it.'(1)

If my Cause be the Cause of Truth, if the Lord whom I worship be none other than

the one true God, He will, ere nine days have elapsed, deliver me from the yoke

of your tyranny. Should He fail to achieve my deliverance, you are free to act

as you desire. You will have irrevocably established the falsity of my belief."

Mulla Muhammad, recognising his inability to accept so bold a challenge, chose

to ignore entirely her message, and sought by every cunning device to accomplish

his purpose.

In those days, ere the hour

which Tahirih had fixed for her deliverance had struck, Baha'u'llah signified

His wish that she should be delivered from her captivity and brought to Tihran.

He determined to establish, in the eyes of the adversary, the truth of her words,

and to frustrate the schemes which her enemies had conceived for her death. Muhammad-Hadiy-i-Farhadi

was accordingly summoned by Him and was entrusted with the task of effecting her

immediate transference to His own home in Tihran. Muhammad-Hadi was charged to

deliver a sealed letter to his wife, Khatun-Jan, and instruct her to proceed,

in the guise of a beggar, to the house where Tahirih was confined; to deliver

the letter into her hands; to wait awhile at the entrance of her house, until

she should join her, and then to hasten with her and commit her to his care. "As

soon as Tahirih has joined you," Baha'u'llah urged the emissary, "start immediately

for Tihran. This very night, I shall despatch to the neighbourhood of the gate

of Qazvin an attendant, with three horses, that you will take with you and station

at a place that you will appoint outside the walls of Qazvin. You will conduct

Tahirih to that spot, will mount the horses, and will, by an unfrequented route,

endeavour to reach at daybreak the outskirts of the capital. As soon as the gates

are opened, you must enter the city and proceed immediately to My house. You should

exercise the utmost caution lest her identity be disclosed. The Almighty will

assuredly guide your steps and will surround you with His unfailing protection."

In those days, ere the hour

which Tahirih had fixed for her deliverance had struck, Baha'u'llah signified

His wish that she should be delivered from her captivity and brought to Tihran.

He determined to establish, in the eyes of the adversary, the truth of her words,

and to frustrate the schemes which her enemies had conceived for her death. Muhammad-Hadiy-i-Farhadi

was accordingly summoned by Him and was entrusted with the task of effecting her

immediate transference to His own home in Tihran. Muhammad-Hadi was charged to

deliver a sealed letter to his wife, Khatun-Jan, and instruct her to proceed,

in the guise of a beggar, to the house where Tahirih was confined; to deliver

the letter into her hands; to wait awhile at the entrance of her house, until

she should join her, and then to hasten with her and commit her to his care. "As

soon as Tahirih has joined you," Baha'u'llah urged the emissary, "start immediately

for Tihran. This very night, I shall despatch to the neighbourhood of the gate

of Qazvin an attendant, with three horses, that you will take with you and station

at a place that you will appoint outside the walls of Qazvin. You will conduct

Tahirih to that spot, will mount the horses, and will, by an unfrequented route,

endeavour to reach at daybreak the outskirts of the capital. As soon as the gates

are opened, you must enter the city and proceed immediately to My house. You should

exercise the utmost caution lest her identity be disclosed. The Almighty will

assuredly guide your steps and will surround you with His unfailing protection."

285

Fortified by the assurance of Baha'u'llah,

Muhammad-Hadi set out immediately to carry out the instructions he had received.

Unhampered by any obstacle, he, ably and faithfully, acquitted himself of his

task, and was able to conduct Tahirih safely, at the appointed hour, to the home

of his Master. Her sudden and mysterious removal from Qazvin filled her friends

and foes alike with consternation. The whole night, they searched the houses and

were baffled in their efforts to find her. The fulfilment of the prediction she

had uttered astounded even the most sceptical among her opponents. A few were

made to realise the supernatural character of the Faith she had espoused, and

submitted willingly to its claims. Mirza Abdu'l-Vahhab, her own brother, acknowledged,

that very day, the truth of the Revelation, but failed to demonstrate subsequently

by his acts the sincerity of his belief.(1)

Fortified by the assurance of Baha'u'llah,

Muhammad-Hadi set out immediately to carry out the instructions he had received.

Unhampered by any obstacle, he, ably and faithfully, acquitted himself of his

task, and was able to conduct Tahirih safely, at the appointed hour, to the home

of his Master. Her sudden and mysterious removal from Qazvin filled her friends

and foes alike with consternation. The whole night, they searched the houses and

were baffled in their efforts to find her. The fulfilment of the prediction she

had uttered astounded even the most sceptical among her opponents. A few were

made to realise the supernatural character of the Faith she had espoused, and

submitted willingly to its claims. Mirza Abdu'l-Vahhab, her own brother, acknowledged,

that very day, the truth of the Revelation, but failed to demonstrate subsequently

by his acts the sincerity of his belief.(1)

The hour which Tahirih had

fixed for her deliverance found her already securely established under the sheltering

shadow of Baha'u'llah. She knew full well into whose presence she had been admitted;

she was profoundly aware of the sacredness of the hospitality she had been so

graciously accorded.(2) As it

was with her acceptance of the Faith proclaimed by the Bab when she, unwarned

and unsummoned, had hailed His Message and recognised its truth, so did she perceive

through her own intuitive knowledge the future glory of Baha'u'llah. It was in

the year '60, while in Karbila, that she alluded in her odes to her recognition

of the Truth He was to reveal. I have myself been shown in Tihran, in the

The hour which Tahirih had

fixed for her deliverance found her already securely established under the sheltering

shadow of Baha'u'llah. She knew full well into whose presence she had been admitted;

she was profoundly aware of the sacredness of the hospitality she had been so

graciously accorded.(2) As it

was with her acceptance of the Faith proclaimed by the Bab when she, unwarned

and unsummoned, had hailed His Message and recognised its truth, so did she perceive

through her own intuitive knowledge the future glory of Baha'u'llah. It was in

the year '60, while in Karbila, that she alluded in her odes to her recognition

of the Truth He was to reveal. I have myself been shown in Tihran, in the

286

home of Siyyid Muhammad,

whom Tahirih had styled Fata'l-Malih, the verses which she, in her own handwriting,

had penned, every letter of which bore eloquent testimony to her faith in the

exalted Missions of both the Bab and Baha'u'llah. In that ode the following verse

occurs: "The effulgence of the Abha Beauty hath pierced the veil of night; behold

the souls of His lovers dancing, moth-like, in the light that has flashed from

His face!" It was her steadfast conviction in the unconquerable power of Baha'u'llah

that prompted her to utter her prediction with such confidence, and to fling her

challenge so boldly in the face of her enemies. Nothing short of an immovable

faith in the unfailing efficacy of that power could have induced her, in the darkest

hours of her captivity, to assert with such courage and assurance the approach

of her victory.

A few days after Tahirih's

arrival at Tihran, Baha'u'llah decided to send her to Khurasan in the company

of the believers who were preparing to depart for that province. He too had determined

to leave the capital and take the same direction a few days later. He

accordingly summoned Aqay-i-Kalim and instructed him to take immediately the necessary

measures to ensure the removal of Tahirih, together with her woman attendant,

Qanitih, to a place outside the gate of the capital, from whence they were, later

on, to proceed to Khurasan. He cautioned him to exercise the utmost care and vigilance

lest the guards who were stationed at the entrance of the city, and who had been

ordered to refuse the passage of women through the gates without a permit, should

discover her identity and prevent her departure.

A few days after Tahirih's

arrival at Tihran, Baha'u'llah decided to send her to Khurasan in the company

of the believers who were preparing to depart for that province. He too had determined

to leave the capital and take the same direction a few days later. He

accordingly summoned Aqay-i-Kalim and instructed him to take immediately the necessary

measures to ensure the removal of Tahirih, together with her woman attendant,

Qanitih, to a place outside the gate of the capital, from whence they were, later

on, to proceed to Khurasan. He cautioned him to exercise the utmost care and vigilance

lest the guards who were stationed at the entrance of the city, and who had been

ordered to refuse the passage of women through the gates without a permit, should

discover her identity and prevent her departure.

I have heard Aqay-i-Kalim recount the following:

"Putting our trust in God, we rode out, Tahirih, her attendant, and I, to a place

in the vicinity of the capital. None of the guards who were stationed at the gate

of Shimiran raised the slightest objection, nor did they enquire regarding our

destination. At a distance of two farsangs(1)

from the capital, we alighted in the midst of an orchard abundantly watered and

situated at the foot of a mountain, in the centre of which was a house that seemed

completely deserted. As I went about in search of the proprietor, I chanced to

meet an old

I have heard Aqay-i-Kalim recount the following:

"Putting our trust in God, we rode out, Tahirih, her attendant, and I, to a place

in the vicinity of the capital. None of the guards who were stationed at the gate

of Shimiran raised the slightest objection, nor did they enquire regarding our

destination. At a distance of two farsangs(1)

from the capital, we alighted in the midst of an orchard abundantly watered and

situated at the foot of a mountain, in the centre of which was a house that seemed

completely deserted. As I went about in search of the proprietor, I chanced to

meet an old

287

man who was watering his

plants. In answer to my enquiry, he explained that a dispute had arisen between

the owner and his tenants, as a result of which those who occupied the place had

deserted it. `I have been asked by the owner,' he added, `to keep guard over this

property until the settlement of the dispute.' I was greatly delighted with the

information he gave me, and asked him to share with us our luncheon. When, later

in the day, I decided to depart for Tihran, I found him willing to watch over

and guard Tahirih and her attendant. As I committed them to his care, I assured

him that I would either myself return that evening or send a trusted attendant

whom I would follow the next morning with all the necessary requirements for the

journey to Khurasan.

"Upon my arrival at Tihran, I despatched Mulla

Baqir, one of the Letters of the Living, together with an attendant, to join Tahirih.

I informed Baha'u'llah of her safe departure from the capital. He was greatly

pleased at the information I gave Him, and named that orchard `Bagh-i-Jannat.'(1)

`That house,' He remarked, `has been providentially prepared for your reception,

that you may entertain in it the loved ones of God.'

"Upon my arrival at Tihran, I despatched Mulla

Baqir, one of the Letters of the Living, together with an attendant, to join Tahirih.

I informed Baha'u'llah of her safe departure from the capital. He was greatly

pleased at the information I gave Him, and named that orchard `Bagh-i-Jannat.'(1)

`That house,' He remarked, `has been providentially prepared for your reception,

that you may entertain in it the loved ones of God.'

"Tahirih tarried seven days

in that spot, after which she set out, accompanied by Muhammad-Hasan-i-Qazvini,

surnamed Fata, and a few others, in the direction of Khurasan. I was commanded

by Baha'u'llah to arrange for her departure and to provide whatever might be required

for her journey."

"Tahirih tarried seven days

in that spot, after which she set out, accompanied by Muhammad-Hasan-i-Qazvini,

surnamed Fata, and a few others, in the direction of Khurasan. I was commanded

by Baha'u'llah to arrange for her departure and to provide whatever might be required

for her journey."

S THE appointed hour approached when, according to the dispensations

of Providence, the veil which still concealed the fundamental verities of the

Faith was to be rent asunder, there blazed forth in the heart of Khurasan a flame

of such consuming intensity that the most formidable obstacles standing in the

way of the ultimate recognition of the Cause melted away and vanished.(1)

That fire caused such a conflagration in the hearts of men that the effects of

its quickening power were felt in the most outlying provinces of Persia. It obliterated

every trace of the misgivings and doubts which had still lingered in the hearts

of the believers, and had hitherto hindered them from apprehending the full measure

of its glory. The decree of the enemy had condemned to perpetual isolation Him

who was the embodiment of the beauty of God, and sought thereby to quench for

all time the flame of His love. The hand of Omnipotence, however, was busily engaged,

at a time when the host of evil-doers were darkly plotting against Him, in confounding

their schemes and in nullifying their efforts. In the easternmost province of

Persia, the Almighty had, through the hand of Quddus, lit a fire that glowed with

the hottest flame in the breasts of the people of Khurasan. And in Karbila, beyond

the western confines of that land, He had kindled the light of Tahirih, a light

that was destined to shed its radiance upon the whole of Persia. From the east

S THE appointed hour approached when, according to the dispensations

of Providence, the veil which still concealed the fundamental verities of the

Faith was to be rent asunder, there blazed forth in the heart of Khurasan a flame

of such consuming intensity that the most formidable obstacles standing in the

way of the ultimate recognition of the Cause melted away and vanished.(1)

That fire caused such a conflagration in the hearts of men that the effects of

its quickening power were felt in the most outlying provinces of Persia. It obliterated

every trace of the misgivings and doubts which had still lingered in the hearts

of the believers, and had hitherto hindered them from apprehending the full measure

of its glory. The decree of the enemy had condemned to perpetual isolation Him

who was the embodiment of the beauty of God, and sought thereby to quench for

all time the flame of His love. The hand of Omnipotence, however, was busily engaged,

at a time when the host of evil-doers were darkly plotting against Him, in confounding

their schemes and in nullifying their efforts. In the easternmost province of

Persia, the Almighty had, through the hand of Quddus, lit a fire that glowed with

the hottest flame in the breasts of the people of Khurasan. And in Karbila, beyond

the western confines of that land, He had kindled the light of Tahirih, a light

that was destined to shed its radiance upon the whole of Persia. From the east

In pursuance of the Divine

decree, in the days when Quddus was still residing in Mashhad, there was revealed

from the pen of the Bab a Tablet addressed to all the believers of Persia, in

which every loyal adherent of the Faith was enjoined to "hasten to the Land of

Kha," the province of Khurasan.(2)

The news of this high injunction spread with marvellous rapidity

and aroused universal enthusiasm. It reached the ears of Tahirih, who, at that

time, was residing in Karbila and was bending every effort to extend the scope

of the Faith she had espoused.(3)

She had left her native town of Qazvin and had arrived, after the death of Siyyid

Kazim, at that holy city, in eager expectation of witnessing the signs which the

departed siyyid had foretold. In the foregoing pages we have seen how instinctively

she had been led to discover the Revelation of the Bab and how spontaneously she

had acknowledged its truth. Unwarned and uninvited, she perceived the dawning

light of the promised Revelation breaking upon the city of Shiraz, and was prompted

to pen her message and plead her fidelity to Him who was the Revealer of that

light.

In pursuance of the Divine

decree, in the days when Quddus was still residing in Mashhad, there was revealed

from the pen of the Bab a Tablet addressed to all the believers of Persia, in

which every loyal adherent of the Faith was enjoined to "hasten to the Land of

Kha," the province of Khurasan.(2)

The news of this high injunction spread with marvellous rapidity

and aroused universal enthusiasm. It reached the ears of Tahirih, who, at that

time, was residing in Karbila and was bending every effort to extend the scope

of the Faith she had espoused.(3)

She had left her native town of Qazvin and had arrived, after the death of Siyyid

Kazim, at that holy city, in eager expectation of witnessing the signs which the

departed siyyid had foretold. In the foregoing pages we have seen how instinctively

she had been led to discover the Revelation of the Bab and how spontaneously she

had acknowledged its truth. Unwarned and uninvited, she perceived the dawning

light of the promised Revelation breaking upon the city of Shiraz, and was prompted

to pen her message and plead her fidelity to Him who was the Revealer of that

light.  The Bab's immediate response

to her declaration of faith which, without attaining His presence, she was moved

to make, animated her zeal and vastly increased her courage. She arose to spread

abroad His teachings, vehemently denounced the corruption and perversity of her

generation, and fearlessly advocated a fundamental revolution in the habits

The Bab's immediate response

to her declaration of faith which, without attaining His presence, she was moved

to make, animated her zeal and vastly increased her courage. She arose to spread

abroad His teachings, vehemently denounced the corruption and perversity of her

generation, and fearlessly advocated a fundamental revolution in the habits

She was able to win to the Cause the revered

widow of Siyyid Kazim, who was born in Shiraz, and was the first among the women

of Karbila to recognise its truth. I have heard Shaykh Sultan describe her extreme

devotion to Tahirih, whom she revered as her spiritual guide and esteemed as her

affectionate companion. He was also a fervent admirer of the character of the

widow of the Siyyid, to whose gentleness of manner he often paid a glowing tribute.

"Such was her attachment to Tahirih," Shaykh Sultan was often heard to remark,

"that she was extremely reluctant to allow that heroine who was a guest in her

house to absent herself, though it were for an hour, from her presence. So great

an attachment on her part did not fail to excite the curiosity and quicken the

faith of her women friends, both Persian and Arab, who were constant visitors

in her home. In the first year of her acceptance of the Message, she suddenly

She was able to win to the Cause the revered

widow of Siyyid Kazim, who was born in Shiraz, and was the first among the women

of Karbila to recognise its truth. I have heard Shaykh Sultan describe her extreme

devotion to Tahirih, whom she revered as her spiritual guide and esteemed as her

affectionate companion. He was also a fervent admirer of the character of the

widow of the Siyyid, to whose gentleness of manner he often paid a glowing tribute.

"Such was her attachment to Tahirih," Shaykh Sultan was often heard to remark,

"that she was extremely reluctant to allow that heroine who was a guest in her

house to absent herself, though it were for an hour, from her presence. So great

an attachment on her part did not fail to excite the curiosity and quicken the

faith of her women friends, both Persian and Arab, who were constant visitors

in her home. In the first year of her acceptance of the Message, she suddenly

Among the men who in Karbila eagerly embraced,

through the efforts of Tahirih, the Cause of the Bab, was a certain Shaykh Salih,

an Arab resident of that city who was the first to shed his blood in the path

of the Faith, in Tihran. She was so profuse in her praise of Shaykh Salih that

a few suspected him of being equal in rank to Quddus. Shaykh Sultan was also among

those who fell under the spell of Tahirih. On his return from Shiraz, he identified

himself with the Faith, boldly and assiduously promoted its interests, and did

his utmost to execute her instructions and wishes. Another admirer

was Shaykh Muhammad-i-Shibl, the father of Muhammad-Mustafa, an Arab native of

Baghdad who ranked high among the ulamas of that city. By the aid of this chosen

band of staunch and able supporters, Tahirih was able to fire the imagination

and to enlist the allegiance of a considerable number of the Persian and Arab

inhabitants of Iraq, most of whom were led by her to join forces with those of

their brethren in Persia who were soon to be called upon to shape by their deeds

the destiny, and to seal with their life-blood the triumph, of the Cause of God.

Among the men who in Karbila eagerly embraced,

through the efforts of Tahirih, the Cause of the Bab, was a certain Shaykh Salih,

an Arab resident of that city who was the first to shed his blood in the path

of the Faith, in Tihran. She was so profuse in her praise of Shaykh Salih that

a few suspected him of being equal in rank to Quddus. Shaykh Sultan was also among

those who fell under the spell of Tahirih. On his return from Shiraz, he identified

himself with the Faith, boldly and assiduously promoted its interests, and did

his utmost to execute her instructions and wishes. Another admirer

was Shaykh Muhammad-i-Shibl, the father of Muhammad-Mustafa, an Arab native of

Baghdad who ranked high among the ulamas of that city. By the aid of this chosen

band of staunch and able supporters, Tahirih was able to fire the imagination

and to enlist the allegiance of a considerable number of the Persian and Arab

inhabitants of Iraq, most of whom were led by her to join forces with those of

their brethren in Persia who were soon to be called upon to shape by their deeds

the destiny, and to seal with their life-blood the triumph, of the Cause of God.

The Bab's appeal, which was originally addressed

to His followers in Persia, was soon transmitted to the adherents of His Faith

in Iraq. Tahirih gloriously responded. Her example was followed immediately by

a large number of her faithful admirers, all of whom expressed their readiness

to journey forthwith to Khurasan. The ulamas of Karbila sought to dissuade her

from undertaking that journey. Perceiving immediately the motive which prompted

them to tender her such advice, and aware of their malignant design, she addressed

to each of these sophists a lengthy epistle in which she set forth her motives

and exposed their dissimulation.(1)

The Bab's appeal, which was originally addressed

to His followers in Persia, was soon transmitted to the adherents of His Faith

in Iraq. Tahirih gloriously responded. Her example was followed immediately by

a large number of her faithful admirers, all of whom expressed their readiness

to journey forthwith to Khurasan. The ulamas of Karbila sought to dissuade her

from undertaking that journey. Perceiving immediately the motive which prompted