HE tale of the tragedy that marked the closing stages of the

Nayriz upheaval spread over the length and breadth of Persia and kindled a startling

enthusiasm in the hearts of those who heard it. It plunged the authorities of

the capital into consternation and nerved them to a resolve of despair. The Amir-Nizam,

the Grand Vazir of Nasiri'd-Din Shah, was particularly overawed by these recurrent

manifestations of an indomitable will, of a fierce and inflexible tenacity of

faith. Though the forces of the imperial army had everywhere triumphed, though

the companions of Mulla Husayn and Vahid had successively been mowed down in a

ruthless carnage at the hands of its officers, yet to the shrewd minds of the

rulers of Tihran it was clear and evident that

HE tale of the tragedy that marked the closing stages of the

Nayriz upheaval spread over the length and breadth of Persia and kindled a startling

enthusiasm in the hearts of those who heard it. It plunged the authorities of

the capital into consternation and nerved them to a resolve of despair. The Amir-Nizam,

the Grand Vazir of Nasiri'd-Din Shah, was particularly overawed by these recurrent

manifestations of an indomitable will, of a fierce and inflexible tenacity of

faith. Though the forces of the imperial army had everywhere triumphed, though

the companions of Mulla Husayn and Vahid had successively been mowed down in a

ruthless carnage at the hands of its officers, yet to the shrewd minds of the

rulers of Tihran it was clear and evident that

Bestirred to action, he summoned his counsellors,

shared with them his fears and his hopes, and acquainted them with the nature

of his plans. "Behold," he exclaimed, "the storm which the Faith of the Siyyid-i-Bab

has provoked in the hearts of my fellow-countrymen! Nothing short of his public

execution can, to my mind, enable this distracted country to recover its tranquillity

and peace. Who dare compute the forces that have perished in the course of the

engagements at Shaykh Tabarsi? Who can estimate the efforts exerted to secure

that victory? No sooner had the mischief that convulsed Mazindaran been suppressed,

than the flames of another sedition blazed forth in the province of Fars, bringing

in its wake so much suffering to my people. We had no sooner succeeded in quelling

the revolt that had ravaged the south, than another insurrection breaks out in

the north, sweeping in its vortex Zanjan and its surroundings. If you are able

to advise a remedy, acquaint me with it, for my sole purpose is to ensure the

peace and honour of my countrymen."

Bestirred to action, he summoned his counsellors,

shared with them his fears and his hopes, and acquainted them with the nature

of his plans. "Behold," he exclaimed, "the storm which the Faith of the Siyyid-i-Bab

has provoked in the hearts of my fellow-countrymen! Nothing short of his public

execution can, to my mind, enable this distracted country to recover its tranquillity

and peace. Who dare compute the forces that have perished in the course of the

engagements at Shaykh Tabarsi? Who can estimate the efforts exerted to secure

that victory? No sooner had the mischief that convulsed Mazindaran been suppressed,

than the flames of another sedition blazed forth in the province of Fars, bringing

in its wake so much suffering to my people. We had no sooner succeeded in quelling

the revolt that had ravaged the south, than another insurrection breaks out in

the north, sweeping in its vortex Zanjan and its surroundings. If you are able

to advise a remedy, acquaint me with it, for my sole purpose is to ensure the

peace and honour of my countrymen."  Not a single voice dared venture a reply,

except that of Mirza Aqa Khani-i-Nuri, the Minister of War, who pleaded

Not a single voice dared venture a reply,

except that of Mirza Aqa Khani-i-Nuri, the Minister of War, who pleaded

Disregarding the advice of

his counsellor, the Amir-Nizam despatched his orders to Navvab Hamzih Mirza, the

governor of Adhirbayjan, who was distinguished among the princes of royal blood

for his kind-heartedness and rectitude of conduct, to summon the Bab to Tabriz.(1)

He was careful not to divulge to the prince his real purpose. The Navvab, assuming

that the intention of the minister was to enable his Captive to return to His

home, immediately directed one of his trusted officers, together with a mounted

escort, to proceed to Chihriq, where the Bab still lay confined, and to bring

Him back to Tabriz. He recommended Him to their care, urging them to exercise

towards Him the utmost consideration.

Disregarding the advice of

his counsellor, the Amir-Nizam despatched his orders to Navvab Hamzih Mirza, the

governor of Adhirbayjan, who was distinguished among the princes of royal blood

for his kind-heartedness and rectitude of conduct, to summon the Bab to Tabriz.(1)

He was careful not to divulge to the prince his real purpose. The Navvab, assuming

that the intention of the minister was to enable his Captive to return to His

home, immediately directed one of his trusted officers, together with a mounted

escort, to proceed to Chihriq, where the Bab still lay confined, and to bring

Him back to Tabriz. He recommended Him to their care, urging them to exercise

towards Him the utmost consideration.  Forty days before the arrival

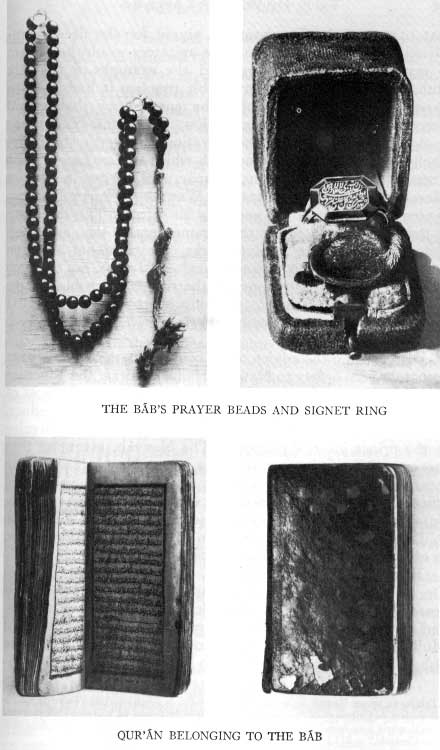

of that officer at Chihriq, the Bab collected all the documents and Tablets in

His possession and, placing them, with His pen-case, His seals, and agate rings,

in a coffer, entrusted them to the care of Mulla Baqir, one of the Letters of

the Living. To him He also delivered a letter addressed to Mirza Ahmad, His amanuensis,

Forty days before the arrival

of that officer at Chihriq, the Bab collected all the documents and Tablets in

His possession and, placing them, with His pen-case, His seals, and agate rings,

in a coffer, entrusted them to the care of Mulla Baqir, one of the Letters of

the Living. To him He also delivered a letter addressed to Mirza Ahmad, His amanuensis,

Mulla Baqir departed forthwith for Qazvin.

Within eighteen days he reached that town and was informed that Mirza Ahmad had

departed for Qum. He left immediately for that destination and arrived towards

the middle of the month of Sha'ban.(1)

I was then in Qum, together with a certain Sadiq-i-Tabrizi, whom Mirza Ahmad had

sent to fetch me from Zarand. I was living in the same house with Mirza Ahmad,

a house which he had hired in the Bagh-Panbih quarter. In those days Shaykh Azim,

Siyyid Isma'il, and a number of other companions likewise were dwelling with us.

Mulla Baqir delivered the trust into the hands of Mirza Ahmad, who, at the insistence

of Shaykh Azim, opened it before us. We marvelled when we beheld, among the things

which that coffer contained, a scroll of blue paper, of the most delicate texture,

on which the Bab, in His own exquisite handwriting, which was a fine shikastih

script, had penned, in the form of a pentacle, what numbered about five hundred

verses, all consisting of derivatives from the word "Baha."(2)

That scroll was in a state of perfect preservation, was spotlessly clean, and

gave the impression, at first sight, of being a printed rather than a written

page. So fine and intricate was the penmanship that, viewed at a distance, the

writing appeared as a single wash of ink on the paper. We were overcome with admiration

as we gazed upon a masterpiece which no calligraphist, we believed, could rival.

That scroll was replaced in the coffer and handed back to Mirza Ahmad, who, on

the very day he received it, proceeded to Tihran. Ere he departed, he informed

us that all he could divulge of that letter was the injunction that the trust

was to be delivered into the hands of Jinab-i-Baha(3)

in Tihran.(4)

Mulla Baqir departed forthwith for Qazvin.

Within eighteen days he reached that town and was informed that Mirza Ahmad had

departed for Qum. He left immediately for that destination and arrived towards

the middle of the month of Sha'ban.(1)

I was then in Qum, together with a certain Sadiq-i-Tabrizi, whom Mirza Ahmad had

sent to fetch me from Zarand. I was living in the same house with Mirza Ahmad,

a house which he had hired in the Bagh-Panbih quarter. In those days Shaykh Azim,

Siyyid Isma'il, and a number of other companions likewise were dwelling with us.

Mulla Baqir delivered the trust into the hands of Mirza Ahmad, who, at the insistence

of Shaykh Azim, opened it before us. We marvelled when we beheld, among the things

which that coffer contained, a scroll of blue paper, of the most delicate texture,

on which the Bab, in His own exquisite handwriting, which was a fine shikastih

script, had penned, in the form of a pentacle, what numbered about five hundred

verses, all consisting of derivatives from the word "Baha."(2)

That scroll was in a state of perfect preservation, was spotlessly clean, and

gave the impression, at first sight, of being a printed rather than a written

page. So fine and intricate was the penmanship that, viewed at a distance, the

writing appeared as a single wash of ink on the paper. We were overcome with admiration

as we gazed upon a masterpiece which no calligraphist, we believed, could rival.

That scroll was replaced in the coffer and handed back to Mirza Ahmad, who, on

the very day he received it, proceeded to Tihran. Ere he departed, he informed

us that all he could divulge of that letter was the injunction that the trust

was to be delivered into the hands of Jinab-i-Baha(3)

in Tihran.(4)

Faithful to the instructions

he had received from Navvab Hamzih Mirza, that officer conducted the Bab to Tabriz

and showed Him the utmost respect and consideration. The prince had instructed

one of his friends to accommodate Him in his home and to treat Him with extreme

deference. Three days after the Bab's arrival, a fresh order was received from

the Grand Vazir, commanding the prince to carry out the execution of his Prisoner

on the very day the farman(1)

would reach him. Whoever would profess himself His follower was likewise to be

condemned to death. The Armenian regiment of Urumiyyih, whose colonel was Sam

Khan, was ordered to shoot Him, in the courtyard of the barracks of Tabriz, which

were situated in the centre of the city.

Faithful to the instructions

he had received from Navvab Hamzih Mirza, that officer conducted the Bab to Tabriz

and showed Him the utmost respect and consideration. The prince had instructed

one of his friends to accommodate Him in his home and to treat Him with extreme

deference. Three days after the Bab's arrival, a fresh order was received from

the Grand Vazir, commanding the prince to carry out the execution of his Prisoner

on the very day the farman(1)

would reach him. Whoever would profess himself His follower was likewise to be

condemned to death. The Armenian regiment of Urumiyyih, whose colonel was Sam

Khan, was ordered to shoot Him, in the courtyard of the barracks of Tabriz, which

were situated in the centre of the city.  The prince expressed his

consternation to the bearer of the farman, Mirza Hasan Khan, the Vazir-Nizam and

brother of the Grand Vazir. "The Amir," he told him, "would do better to entrust

me with services of greater merit than the one with which he has now commissioned

me. The task I am called upon to perform is a task that only ignoble people would

accept. I am neither Ibn-i-Ziyad nor Ibn-i-Sa'd(2)

that he should call upon me to slay an innocent descendant of the Prophet of God."

Mirza Hasan Khan reported these sayings of the prince to his brother, who thereupon

ordered him to follow, himself, without delay and in their entirety, the instructions

he had already given. "Relieve us," the Vazir urged his brother, "from this anxiety

that weighs upon our hearts, and let this affair be brought to an end ere the

month of Ramadan breaks upon us, that we may enter the period of fasting with

undisturbed tranquillity." Mirza Hasan Khan attempted to acquaint the prince with

these fresh instructions, but failed in his efforts, as the prince, pretending

to be ill, refused to meet him. Undeterred by this refusal, he issued his instructions

for the immediate transfer of the Bab and those in His company from the house

The prince expressed his

consternation to the bearer of the farman, Mirza Hasan Khan, the Vazir-Nizam and

brother of the Grand Vazir. "The Amir," he told him, "would do better to entrust

me with services of greater merit than the one with which he has now commissioned

me. The task I am called upon to perform is a task that only ignoble people would

accept. I am neither Ibn-i-Ziyad nor Ibn-i-Sa'd(2)

that he should call upon me to slay an innocent descendant of the Prophet of God."

Mirza Hasan Khan reported these sayings of the prince to his brother, who thereupon

ordered him to follow, himself, without delay and in their entirety, the instructions

he had already given. "Relieve us," the Vazir urged his brother, "from this anxiety

that weighs upon our hearts, and let this affair be brought to an end ere the

month of Ramadan breaks upon us, that we may enter the period of fasting with

undisturbed tranquillity." Mirza Hasan Khan attempted to acquaint the prince with

these fresh instructions, but failed in his efforts, as the prince, pretending

to be ill, refused to meet him. Undeterred by this refusal, he issued his instructions

for the immediate transfer of the Bab and those in His company from the house

Deprived of His turban and

sash, the twin emblems of His noble lineage, the Bab, together with Siyyid Husayn,

His amanuensis, was driven to yet another confinement which He well knew was but

a step further on the way leading Him to the goal He had set Himself to attain.

That day witnessed a tremendous commotion in the city of Tabriz. The great convulsion

associated in the ideas of its inhabitants with the Day of Judgment seemed at

last to have come upon them. Never had that city experienced a turmoil so fierce

and so mysterious as the one which seized its inhabitants on the day the Bab was

led to that place which was to be the scene of His martyrdom. As He approached

the courtyard of the barracks, a youth suddenly leaped forward who, in his eagerness

to overtake Him, had forced his way through the crowd, utterly ignoring the risks

and perils which such an attempt might involve. His face was haggard, his feet

were bare, and his hair dishevelled. Breathless with excitement and exhausted

with fatigue, he flung himself at the feet of the Bab and, seizing the hem of

His garment, passionately implored Him: "Send me not from Thee, O Master. Wherever

Thou goest, suffer me to follow Thee." "Muhammad-'Ali," answered the Bab, "arise,

and rest assured that you will be with Me.(1)

To-morrow you shall witness what God has decreed." Two other companions, unable

to contain themselves, rushed forward and assured Him of their unalterable loyalty.

These, together with Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Zunuzi, were seized and placed in

the same cell in which the Bab and Siyyid Husayn were confined.

Deprived of His turban and

sash, the twin emblems of His noble lineage, the Bab, together with Siyyid Husayn,

His amanuensis, was driven to yet another confinement which He well knew was but

a step further on the way leading Him to the goal He had set Himself to attain.

That day witnessed a tremendous commotion in the city of Tabriz. The great convulsion

associated in the ideas of its inhabitants with the Day of Judgment seemed at

last to have come upon them. Never had that city experienced a turmoil so fierce

and so mysterious as the one which seized its inhabitants on the day the Bab was

led to that place which was to be the scene of His martyrdom. As He approached

the courtyard of the barracks, a youth suddenly leaped forward who, in his eagerness

to overtake Him, had forced his way through the crowd, utterly ignoring the risks

and perils which such an attempt might involve. His face was haggard, his feet

were bare, and his hair dishevelled. Breathless with excitement and exhausted

with fatigue, he flung himself at the feet of the Bab and, seizing the hem of

His garment, passionately implored Him: "Send me not from Thee, O Master. Wherever

Thou goest, suffer me to follow Thee." "Muhammad-'Ali," answered the Bab, "arise,

and rest assured that you will be with Me.(1)

To-morrow you shall witness what God has decreed." Two other companions, unable

to contain themselves, rushed forward and assured Him of their unalterable loyalty.

These, together with Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Zunuzi, were seized and placed in

the same cell in which the Bab and Siyyid Husayn were confined.  I have heard Siyyid Husayn

bear witness to the following: "That night the face of the Bab was aglow with

joy, a joy such as had never shone from His countenance. Indifferent to the storm

that raged about Him, He conversed with us with gaiety and cheerfulness. The sorrows

that had weighed

I have heard Siyyid Husayn

bear witness to the following: "That night the face of the Bab was aglow with

joy, a joy such as had never shone from His countenance. Indifferent to the storm

that raged about Him, He conversed with us with gaiety and cheerfulness. The sorrows

that had weighed

Early in the morning, Mirza Hasan Khan ordered

his farrash-bashi(1)

to conduct the Bab into the presence of the leading mujtahids of the city and

to obtain from them the authorisation required for His execution.(2)

As the Bab was leaving the barracks, Siyyid Husayn asked Him what he should do.

"Confess not your faith," He advised him. "Thereby you will be enabled, when the

hour comes, to convey to those who are destined to hear you, the things of which

you alone are aware." He was engaged in a confidential conversation with him when

the farrash-bashi suddenly

Early in the morning, Mirza Hasan Khan ordered

his farrash-bashi(1)

to conduct the Bab into the presence of the leading mujtahids of the city and

to obtain from them the authorisation required for His execution.(2)

As the Bab was leaving the barracks, Siyyid Husayn asked Him what he should do.

"Confess not your faith," He advised him. "Thereby you will be enabled, when the

hour comes, to convey to those who are destined to hear you, the things of which

you alone are aware." He was engaged in a confidential conversation with him when

the farrash-bashi suddenly

When Mirza Muhammad-'Ali

was ushered into the presence of the mujtahids, he was repeatedly urged, in view

When Mirza Muhammad-'Ali

was ushered into the presence of the mujtahids, he was repeatedly urged, in view

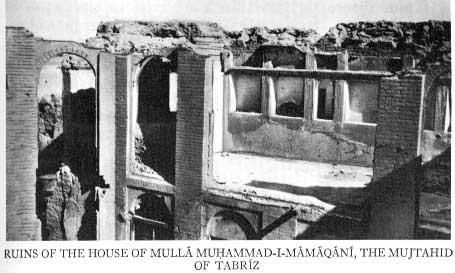

The Bab was, in His turn,

brought before Mulla Muhammad-i-Mamaqani. No sooner had he recognised Him than

he seized the death-warrant he himself had previously written and, handing it

to his attendant, bade him deliver it to the farrash-bashi. "No need," he cried,

"to bring the Siyyid-i-Bab into my presence. This death-warrant I penned the very

day I met him at the gathering presided over by the Vali-'Ahd. He surely is the

same man whom I saw on that occasion, and has not, in the meantime, surrendered

any of his claims."

The Bab was, in His turn,

brought before Mulla Muhammad-i-Mamaqani. No sooner had he recognised Him than

he seized the death-warrant he himself had previously written and, handing it

to his attendant, bade him deliver it to the farrash-bashi. "No need," he cried,

"to bring the Siyyid-i-Bab into my presence. This death-warrant I penned the very

day I met him at the gathering presided over by the Vali-'Ahd. He surely is the

same man whom I saw on that occasion, and has not, in the meantime, surrendered

any of his claims."  From thence the Bab was conducted to the house

of Mirza Baqir, the son of Mirza Ahmad, to whom he had recently succeeded. When

they arrived, they found his attendant standing at the gate and holding in his

hand the Bab's death-warrant. "No need to enter," he told them. "My master is

already satisfied that his father was right in pronouncing the sentence of death.

He can do no better than follow his example."

From thence the Bab was conducted to the house

of Mirza Baqir, the son of Mirza Ahmad, to whom he had recently succeeded. When

they arrived, they found his attendant standing at the gate and holding in his

hand the Bab's death-warrant. "No need to enter," he told them. "My master is

already satisfied that his father was right in pronouncing the sentence of death.

He can do no better than follow his example."  Mulla Murtada-Quli, following in the footsteps

of the other two mujtahids, had previously issued his own written testimony and

refused to meet face to face his dreaded opponent. No sooner had the farrash-bashi

secured the necessary documents than he delivered his Captive into the hands of

Sam Khan, assuring him that he could proceed with his task now that he had obtained

the sanction of the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of the realm.

Mulla Murtada-Quli, following in the footsteps

of the other two mujtahids, had previously issued his own written testimony and

refused to meet face to face his dreaded opponent. No sooner had the farrash-bashi

secured the necessary documents than he delivered his Captive into the hands of

Sam Khan, assuring him that he could proceed with his task now that he had obtained

the sanction of the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of the realm.  Siyyid Husayn had remained confined in the

same room in which he had spent the previous night with the Bab. They were proceeding

to place Mirza Muhammad-'Ali in that same room, when he burst forth into tears

and entreated them to allow him to remain with his Master. He was delivered into

the hands of Sam Khan, who was ordered to execute him also, if he persisted in

his refusal to deny his Faith.

Siyyid Husayn had remained confined in the

same room in which he had spent the previous night with the Bab. They were proceeding

to place Mirza Muhammad-'Ali in that same room, when he burst forth into tears

and entreated them to allow him to remain with his Master. He was delivered into

the hands of Sam Khan, who was ordered to execute him also, if he persisted in

his refusal to deny his Faith.  Sam Khan was, in the meantime, finding himself

increasingly affected by the behaviour of his Captive and the treatment that had

been meted out to Him. He was seized with great fear lest his action should bring

upon him the

Sam Khan was, in the meantime, finding himself

increasingly affected by the behaviour of his Captive and the treatment that had

been meted out to Him. He was seized with great fear lest his action should bring

upon him the

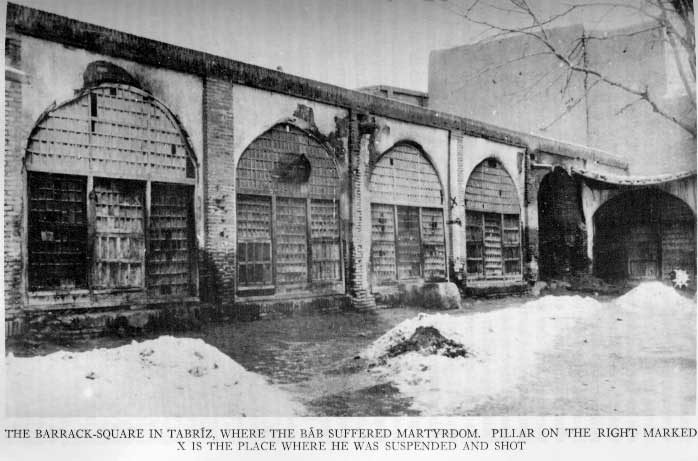

Sam Khan ordered his men to drive a nail into

the pillar that lay between the door of the room that Siyyid Husayn occupied and

the entrance to the adjoining one, and to make fast two ropes to that nail, from

which the Bab and His companion were to be separately suspended.(1)

Mirza Muhammad-'Ali begged Sam Khan to be placed in such a manner that his own

body would shield that of the Bab.(2)

He was eventually suspended in such a position that his head reposed on the breast

of his Master. As soon as they were fastened, a regiment of soldiers ranged itself

in three files, each of two hundred and fifty men, each of which was ordered to

open fire in its turn until the whole detachment had discharged the volleys of

its bullets.(3) The smoke of

the firing of the seven hundred and fifty rifles was such as to turn the light

of the noonday sun into darkness. There had crowded onto

Sam Khan ordered his men to drive a nail into

the pillar that lay between the door of the room that Siyyid Husayn occupied and

the entrance to the adjoining one, and to make fast two ropes to that nail, from

which the Bab and His companion were to be separately suspended.(1)

Mirza Muhammad-'Ali begged Sam Khan to be placed in such a manner that his own

body would shield that of the Bab.(2)

He was eventually suspended in such a position that his head reposed on the breast

of his Master. As soon as they were fastened, a regiment of soldiers ranged itself

in three files, each of two hundred and fifty men, each of which was ordered to

open fire in its turn until the whole detachment had discharged the volleys of

its bullets.(3) The smoke of

the firing of the seven hundred and fifty rifles was such as to turn the light

of the noonday sun into darkness. There had crowded onto

As soon as the cloud of smoke

had cleared away, an astounded multitude were looking upon a scene which their

eyes could scarcely believe. There, standing before them alive and unhurt, was

the companion of the Bab, whilst He Himself had vanished uninjured from their

sight. Though the cords with which they were suspended had been rent in pieces

by the bullets, yet their bodies had miraculously escaped the volleys.(1)

Even the tunic which Mirza Muhammad-'Ali was wearing had, despite the thickness

of the smoke, remained unsullied. "The Siyyid-i-Bab has gone from our sight!"

rang out the voices of the bewildered multitude. They set out in a frenzied search

for Him, and found Him, eventually, seated in the same room which He had occupied

the night before, engaged in completing His interrupted conversation, with Siyyid

Husayn. An expression of unruffled calm was upon His face. His body had emerged

unscathed from the shower of bullets which the regiment had directed against Him.

"I have finished My conversation with Siyyid Husayn," the Bab told the farrash-bashi.

"Now you may proceed to fulfil your intention." The man was too much shaken to

resume what he had already attempted. Refusing to accomplish

his duty, he, that same moment, left that scene and resigned his post. He related

all that he had seen to

As soon as the cloud of smoke

had cleared away, an astounded multitude were looking upon a scene which their

eyes could scarcely believe. There, standing before them alive and unhurt, was

the companion of the Bab, whilst He Himself had vanished uninjured from their

sight. Though the cords with which they were suspended had been rent in pieces

by the bullets, yet their bodies had miraculously escaped the volleys.(1)

Even the tunic which Mirza Muhammad-'Ali was wearing had, despite the thickness

of the smoke, remained unsullied. "The Siyyid-i-Bab has gone from our sight!"

rang out the voices of the bewildered multitude. They set out in a frenzied search

for Him, and found Him, eventually, seated in the same room which He had occupied

the night before, engaged in completing His interrupted conversation, with Siyyid

Husayn. An expression of unruffled calm was upon His face. His body had emerged

unscathed from the shower of bullets which the regiment had directed against Him.

"I have finished My conversation with Siyyid Husayn," the Bab told the farrash-bashi.

"Now you may proceed to fulfil your intention." The man was too much shaken to

resume what he had already attempted. Refusing to accomplish

his duty, he, that same moment, left that scene and resigned his post. He related

all that he had seen to

I was privileged to meet, subsequently, this

same Mirza Siyyid Muhsin, who conducted me to the scene of the Bab's martyrdom

and showed me the wall where He had been suspended. I was taken to the room in

which He had been found conversing with Siyyid Husayn, and was shown the very

spot where He had been seated. I saw the very nail which His enemies had hammered

into the wall and to which the rope which had supported His body had been attached.

I was privileged to meet, subsequently, this

same Mirza Siyyid Muhsin, who conducted me to the scene of the Bab's martyrdom

and showed me the wall where He had been suspended. I was taken to the room in

which He had been found conversing with Siyyid Husayn, and was shown the very

spot where He had been seated. I saw the very nail which His enemies had hammered

into the wall and to which the rope which had supported His body had been attached.

Sam Khan was likewise stunned

by the force of this tremendous revelation. He ordered his men to leave the barracks

immediately, and refused ever again to associate himself and his regiment with

any act that involved the least injury to the Bab. He swore, as he left that courtyard,

never again to resume that task even though his refusal should entail the loss

of his own life.

Sam Khan was likewise stunned

by the force of this tremendous revelation. He ordered his men to leave the barracks

immediately, and refused ever again to associate himself and his regiment with

any act that involved the least injury to the Bab. He swore, as he left that courtyard,

never again to resume that task even though his refusal should entail the loss

of his own life.  No sooner had Sam Khan departed than Aqa Jan

Khan-i-Khamsih, colonel of the body-guard, known also by the names of Khamsih

and Nasiri, volunteered to carry out the order for execution. On the same wall

and in the same manner, the Bab and His companion were again suspended, while

the regiment formed in line to open fire upon them. Contrariwise to the previous

occasion, when only the cord with which they were suspended had been shot into

pieces, this time their bodies were shattered and were blended into one mass of

mingled flesh and bone.(1) "Had

you believed in Me, O wayward generation," were the last words of the Bab to the

gazing multitude as the regiment was preparing to fire the final volley, "every

one of you would have followed the example of this youth, who stood in rank above

most of you, and willingly would have sacrificed himself in My path. The day will

come when you will have recognised Me; that day I shall have ceased to be with

you."(2)

No sooner had Sam Khan departed than Aqa Jan

Khan-i-Khamsih, colonel of the body-guard, known also by the names of Khamsih

and Nasiri, volunteered to carry out the order for execution. On the same wall

and in the same manner, the Bab and His companion were again suspended, while

the regiment formed in line to open fire upon them. Contrariwise to the previous

occasion, when only the cord with which they were suspended had been shot into

pieces, this time their bodies were shattered and were blended into one mass of

mingled flesh and bone.(1) "Had

you believed in Me, O wayward generation," were the last words of the Bab to the

gazing multitude as the regiment was preparing to fire the final volley, "every

one of you would have followed the example of this youth, who stood in rank above

most of you, and willingly would have sacrificed himself in My path. The day will

come when you will have recognised Me; that day I shall have ceased to be with

you."(2)

The very moment the shots were fired, a gale

of exceptional severity arose and swept over the whole city. A whirlwind of dust

of incredible density obscured the light of the sun and blinded the eyes of the

people. The entire city remained enveloped in that darkness from noon till night.

Even so strange a phenomenon, following immediately in the wake of that still

more astounding failure of Sam Khan's regiment to injure the Bab, was unable to

move

The very moment the shots were fired, a gale

of exceptional severity arose and swept over the whole city. A whirlwind of dust

of incredible density obscured the light of the sun and blinded the eyes of the

people. The entire city remained enveloped in that darkness from noon till night.

Even so strange a phenomenon, following immediately in the wake of that still

more astounding failure of Sam Khan's regiment to injure the Bab, was unable to

move

The martyrdom of the Bab took place at noon

on Sunday, the twenty-eighth of Sha'ban, in the year 1266 A.H.,(1)

thirty-one lunar years, seven months, and twenty-seven days from the day of His

birth in Shiraz.

The martyrdom of the Bab took place at noon

on Sunday, the twenty-eighth of Sha'ban, in the year 1266 A.H.,(1)

thirty-one lunar years, seven months, and twenty-seven days from the day of His

birth in Shiraz.

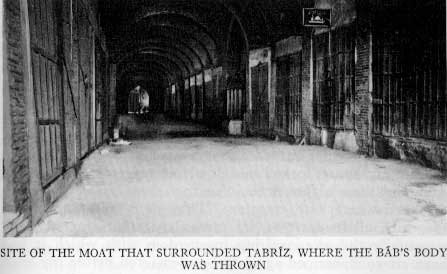

On the evening of that same day, the mangled

bodies of the Bab and His companion were removed from the courtyard

On the evening of that same day, the mangled

bodies of the Bab and His companion were removed from the courtyard

I have heard Haji Ali-'Askar

relate the following: "An official of the Russian consulate, to whom I was related,

showed me that same sketch on the very day it was drawn. It was such a faithful

portrait of the Bab that I looked upon! No bullet had struck His forehead, His

cheeks, or His lips. I gazed upon a smile which seemed to be still lingering upon

His countenance. His body, however, had been severely mutilated. I could recognise

the arms and head of His companion, who seemed to be holding Him in his embrace.

As I gazed horror-struck upon that haunting picture, and saw how those noble traits

had been disfigured, my heart sank within me. I turned away my face in anguish

and, regaining my house, locked myself with my room. For three days and three

nights, I could neither sleep nor eat, so overwhelmed was I with emotion. That

short and tumultuous life, with all its sorrows, its turmoils, its banishments,

and eventually the awe-inspiring martyrdom with which it had been crowned, seemed

again to be re-enacted before my eyes. I tossed upon my bed, writhing in agony

and pain."

I have heard Haji Ali-'Askar

relate the following: "An official of the Russian consulate, to whom I was related,

showed me that same sketch on the very day it was drawn. It was such a faithful

portrait of the Bab that I looked upon! No bullet had struck His forehead, His

cheeks, or His lips. I gazed upon a smile which seemed to be still lingering upon

His countenance. His body, however, had been severely mutilated. I could recognise

the arms and head of His companion, who seemed to be holding Him in his embrace.

As I gazed horror-struck upon that haunting picture, and saw how those noble traits

had been disfigured, my heart sank within me. I turned away my face in anguish

and, regaining my house, locked myself with my room. For three days and three

nights, I could neither sleep nor eat, so overwhelmed was I with emotion. That

short and tumultuous life, with all its sorrows, its turmoils, its banishments,

and eventually the awe-inspiring martyrdom with which it had been crowned, seemed

again to be re-enacted before my eyes. I tossed upon my bed, writhing in agony

and pain."  On the afternoon of the second day after the

Bab's martyrdom, Haji Sulayman Khan, son of Yahya Khan, arrived at Bagh-Mishih,

a suburb of Tabriz, and was received at the house of the Kalantar,(2)

one of his friends and confidants,

On the afternoon of the second day after the

Bab's martyrdom, Haji Sulayman Khan, son of Yahya Khan, arrived at Bagh-Mishih,

a suburb of Tabriz, and was received at the house of the Kalantar,(2)

one of his friends and confidants,

Haji Sulayman Khan immediately reported the

matter

Haji Sulayman Khan immediately reported the

matter

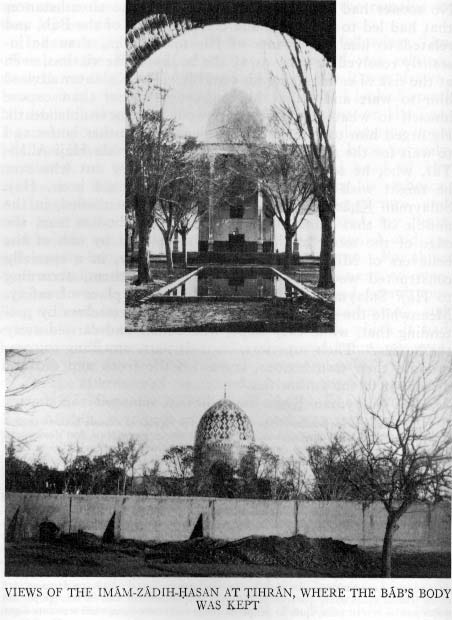

I was myself in Tihran, in the company of

Mirza Ahmad, when the bodies of the Bab and His companion arrived. Baha'u'llah

had in the meantime departed for Karbila, in pursuance of the instructions of

the Amir-Nizam. Aqay-i-Kalim, together with Mirza Ahmad, transferred those remains

from the Imam-Zadih-Hasan,(2)

where they were first taken, to a place the site of which remained unknown to

anyone excepting themselves. That place remained secret until the departure of

Baha'u'llah for Adrianople, at which time Aqay-i-Kalim was charged to inform Munir,

one of his fellow-disciples, of the actual site where the bodies had been laid.

In spite of his search, he was unable to find it. It was subsequently discovered

by Jamal, an old adherent of the Faith, to whom that secret was confided while

Baha'u'llah

I was myself in Tihran, in the company of

Mirza Ahmad, when the bodies of the Bab and His companion arrived. Baha'u'llah

had in the meantime departed for Karbila, in pursuance of the instructions of

the Amir-Nizam. Aqay-i-Kalim, together with Mirza Ahmad, transferred those remains

from the Imam-Zadih-Hasan,(2)

where they were first taken, to a place the site of which remained unknown to

anyone excepting themselves. That place remained secret until the departure of

Baha'u'llah for Adrianople, at which time Aqay-i-Kalim was charged to inform Munir,

one of his fellow-disciples, of the actual site where the bodies had been laid.

In spite of his search, he was unable to find it. It was subsequently discovered

by Jamal, an old adherent of the Faith, to whom that secret was confided while

Baha'u'llah

The first in Tihran to hear

of the circumstances attending that cruel martyrdom, after the Grand Vazir, was

Mirza Aqa Khan-i-Nuri, who had been banished to Kashan by Muhammad Shah when the

Bab was passing through that city. He had assured Haji Mirza Jani, who had acquainted

him with the precepts of the Faith, that if the love he bore for the new Revelation

would cause him to regain his lost position, he would exert his utmost endeavour

to secure the well-being and safety of the persecuted community. Haji Mirza Jani

reported the matter to his Master, who charged him to assure the disgraced minister

that ere long he would be summoned to Tihran and would be invested, by his sovereign,

with a position that would be second to none except that of the Shah himself.

He was warned not to forget his promise, and to strive to carry out his intention.

He was delighted with that message, and renewed the assurance he had given.

The first in Tihran to hear

of the circumstances attending that cruel martyrdom, after the Grand Vazir, was

Mirza Aqa Khan-i-Nuri, who had been banished to Kashan by Muhammad Shah when the

Bab was passing through that city. He had assured Haji Mirza Jani, who had acquainted

him with the precepts of the Faith, that if the love he bore for the new Revelation

would cause him to regain his lost position, he would exert his utmost endeavour

to secure the well-being and safety of the persecuted community. Haji Mirza Jani

reported the matter to his Master, who charged him to assure the disgraced minister

that ere long he would be summoned to Tihran and would be invested, by his sovereign,

with a position that would be second to none except that of the Shah himself.

He was warned not to forget his promise, and to strive to carry out his intention.

He was delighted with that message, and renewed the assurance he had given.  When the news of the Bab's martyrdom reached

him, he had already been promoted, had received the title of I'timadu'd-Dawlih,

and was hoping to be raised to the position of Grand Vazir. He hastened to inform

Baha'u'llah, with whom he was intimately acquainted, of the news he had received,

expressing the hope that the fire he feared would one day bring untold calamity

upon Him, was at last extinguished. "Not so," Baha'u'llah replied. "If this be

true, you can be certain that the flame that has been kindled will, by this very

act, blaze forth more fiercely than ever, and will set up a conflagration such

as the combined forces of the statesmen of this realm will be powerless to quench."

The significance of these words Mirza Aqa Khan was destined to appreciate at a

later time. Scarcely did he imagine, when that prediction was uttered, that the

Faith which had received so staggering a blow could survive its Author. He himself

had, on one occasion, been cured by Baha'u'llah of an illness from which he had

given up all hope of recovery.

When the news of the Bab's martyrdom reached

him, he had already been promoted, had received the title of I'timadu'd-Dawlih,

and was hoping to be raised to the position of Grand Vazir. He hastened to inform

Baha'u'llah, with whom he was intimately acquainted, of the news he had received,

expressing the hope that the fire he feared would one day bring untold calamity

upon Him, was at last extinguished. "Not so," Baha'u'llah replied. "If this be

true, you can be certain that the flame that has been kindled will, by this very

act, blaze forth more fiercely than ever, and will set up a conflagration such

as the combined forces of the statesmen of this realm will be powerless to quench."

The significance of these words Mirza Aqa Khan was destined to appreciate at a

later time. Scarcely did he imagine, when that prediction was uttered, that the

Faith which had received so staggering a blow could survive its Author. He himself

had, on one occasion, been cured by Baha'u'llah of an illness from which he had

given up all hope of recovery.  His son, the Nizamu'l-Mulk, one day asked

him whether he did not think that Baha'u'llah, who, of all the sons of the late

Vazir, had shown Himself the most capable, had failed

His son, the Nizamu'l-Mulk, one day asked

him whether he did not think that Baha'u'llah, who, of all the sons of the late

Vazir, had shown Himself the most capable, had failed

The malicious persistence with which a savage

enemy sought to ill-treat and eventually to destroy the life of the Bab brought

in its wake untold calamities upon Persia and its inhabitants. The men who perpetrated

these atrocities fell victims to gnawing remorse, and in an incredibly short period

were made to suffer ignominious deaths. As to the great mass of its people, who

watched with sullen indifference the tragedy that was being enacted before their

eyes, and who failed to raise a finger in protest against the hideousness of those

cruelties, they fell, in their turn, victims to a misery which all the resources

of the land and the energy of its statesmen were powerless to alleviate. The wind

of adversity blew fiercely upon them, and shook to its foundations their material

prosperity. From the very day the hand of the assailant was stretched forth against

the Bab, and sought to

The malicious persistence with which a savage

enemy sought to ill-treat and eventually to destroy the life of the Bab brought

in its wake untold calamities upon Persia and its inhabitants. The men who perpetrated

these atrocities fell victims to gnawing remorse, and in an incredibly short period

were made to suffer ignominious deaths. As to the great mass of its people, who

watched with sullen indifference the tragedy that was being enacted before their

eyes, and who failed to raise a finger in protest against the hideousness of those

cruelties, they fell, in their turn, victims to a misery which all the resources

of the land and the energy of its statesmen were powerless to alleviate. The wind

of adversity blew fiercely upon them, and shook to its foundations their material

prosperity. From the very day the hand of the assailant was stretched forth against

the Bab, and sought to

The first who arose to ill-treat the Bab was

none other than Husayn Khan, the governor of Shiraz. His disgraceful treatment

of his Captive cost him the lives of thousands who had been committed to his protection

and who connived at his acts. His province was ravaged by a plague which brought

it to the verge of destruction. Impoverished and exhausted, Fars languished helpless

beneath its weight, calling for the charity of its neighbours and the assistance

of its friends. Husayn Khan himself witnessed with bitterness the undoing of all

his labours, was condemned to lead in obscurity the remaining days of his life,

and tottered to his grave, abandoned and forgotten, alike by his friends and his

enemies.

The first who arose to ill-treat the Bab was

none other than Husayn Khan, the governor of Shiraz. His disgraceful treatment

of his Captive cost him the lives of thousands who had been committed to his protection

and who connived at his acts. His province was ravaged by a plague which brought

it to the verge of destruction. Impoverished and exhausted, Fars languished helpless

beneath its weight, calling for the charity of its neighbours and the assistance

of its friends. Husayn Khan himself witnessed with bitterness the undoing of all

his labours, was condemned to lead in obscurity the remaining days of his life,

and tottered to his grave, abandoned and forgotten, alike by his friends and his

enemies.  The next who sought to challenge the Faith

of the Bab

The next who sought to challenge the Faith

of the Bab

As to the regiment which, despite the unaccountable

failure of Sam Khan and his men to destroy the life of the Bab, had volunteered

to renew that attempt, and which eventually riddled His body with its bullets,

two hundred and fifty of its members met their death in that same year, together

with their officers, in a terrible earthquake. While they were resting on a hot

summer day under the shadow of a wall on their way between Ardibil and Tabriz,

absorbed in their games and pleasures, the whole structure suddenly collapsed

and fell upon them, leaving not one survivor. The remaining five hundred suffered

the same fate as that which their own hands had inflicted upon the Bab. Three

years after His martyrdom, that regiment mutinied, and its members were thereupon

mercilessly shot by command of Mirza Sadiq Khan-i-Nuri. Not content with a first

volley, he ordered that a second one be fired in order to ensure that none of

the mutineers had survived. Their bodies were afterwards pierced with spears and

lances, and left exposed to the gaze of the people of Tabriz. That day many of

the inhabitants of the city, recalling the circumstances of the Bab's martyrdom,

wondered at that same fate which had overtaken those who had slain Him. "Could

it be, by any chance, the vengeance

As to the regiment which, despite the unaccountable

failure of Sam Khan and his men to destroy the life of the Bab, had volunteered

to renew that attempt, and which eventually riddled His body with its bullets,

two hundred and fifty of its members met their death in that same year, together

with their officers, in a terrible earthquake. While they were resting on a hot

summer day under the shadow of a wall on their way between Ardibil and Tabriz,

absorbed in their games and pleasures, the whole structure suddenly collapsed

and fell upon them, leaving not one survivor. The remaining five hundred suffered

the same fate as that which their own hands had inflicted upon the Bab. Three

years after His martyrdom, that regiment mutinied, and its members were thereupon

mercilessly shot by command of Mirza Sadiq Khan-i-Nuri. Not content with a first

volley, he ordered that a second one be fired in order to ensure that none of

the mutineers had survived. Their bodies were afterwards pierced with spears and

lances, and left exposed to the gaze of the people of Tabriz. That day many of

the inhabitants of the city, recalling the circumstances of the Bab's martyrdom,

wondered at that same fate which had overtaken those who had slain Him. "Could

it be, by any chance, the vengeance

The prime mover of the forces that precipitated

the Bab's martyrdom, the Amir-Nizam, and also his brother, the Vazir-Nizam, his

chief accomplice, were, within two years of that savage act, subjected to a dreadful

punishment, which ended miserably in their death. The blood of the Amir-Nizam

stains, to this very day, the wall of the bath of Fin,(1)

a witness to the atrocities his own hand had wrought.(2)

The prime mover of the forces that precipitated

the Bab's martyrdom, the Amir-Nizam, and also his brother, the Vazir-Nizam, his

chief accomplice, were, within two years of that savage act, subjected to a dreadful

punishment, which ended miserably in their death. The blood of the Amir-Nizam

stains, to this very day, the wall of the bath of Fin,(1)

a witness to the atrocities his own hand had wrought.(2)