527

CHAPTER XXIV

THE ZANJAN UPHEAVAL

HE spark that had kindled the great conflagrations of Mazindaran

and Nayriz had already set aflame Zanjan(1)

and its surroundings when the Bab met His death in Tabriz. Profound as was His

sorrow at the sad and calamitous fate that had overtaken the heroes of Shaykh

Tabarsi, the news of the no less tragic sufferings that had been the lot of Vahid

and his companions, came as an added blow to His heart, already oppressed by the

weight of manifold afflictions. The consciousness of the dangers that thickened

around Him; the memory of the indignity He endured when He was last conducted

to Tabriz; the strain of a prolonged and rigorous captivity amidst the mountain

fastnesses of Adhirbayjan; the terrible butcheries that marked the closing stages

of the Mazindaran and Nayriz upheavals; the outrages to His Faith wrought by the

persecutors of the Seven Martyrs of Tihran--even these were not all the troubles

HE spark that had kindled the great conflagrations of Mazindaran

and Nayriz had already set aflame Zanjan(1)

and its surroundings when the Bab met His death in Tabriz. Profound as was His

sorrow at the sad and calamitous fate that had overtaken the heroes of Shaykh

Tabarsi, the news of the no less tragic sufferings that had been the lot of Vahid

and his companions, came as an added blow to His heart, already oppressed by the

weight of manifold afflictions. The consciousness of the dangers that thickened

around Him; the memory of the indignity He endured when He was last conducted

to Tabriz; the strain of a prolonged and rigorous captivity amidst the mountain

fastnesses of Adhirbayjan; the terrible butcheries that marked the closing stages

of the Mazindaran and Nayriz upheavals; the outrages to His Faith wrought by the

persecutors of the Seven Martyrs of Tihran--even these were not all the troubles

528

that beclouded the remaining

days of a fast-ebbing life. He was already prostrated by the severity of these

blows when the news of the happenings at Zanjan, which were then beginning to

foreshadow their sad events, reached Him and served to consummate the anguish

of His last days. What

pangs must He have endured

as the shadows of death were fast gathering about Him! In every field, whether

in the north or in the south, the champions of His Faith had been subjected to

undeserved sufferings, had been infamously deceived, had been robbed of their

possessions, and had been inhumanly massacred. And now, as if to fill His cup

of woes to over-flowing,

pangs must He have endured

as the shadows of death were fast gathering about Him! In every field, whether

in the north or in the south, the champions of His Faith had been subjected to

undeserved sufferings, had been infamously deceived, had been robbed of their

possessions, and had been inhumanly massacred. And now, as if to fill His cup

of woes to over-flowing,

529

there broke forth the storm

of Zanjan, the most violent and devastating of them all.(1)

I now proceed to relate the

circumstances that have made of that event one of the most thrilling episodes

in the history of this Revelation. Its chief figure was Hujjat-i-Zanjani, whose

name was Mulla Muhammad-'Ali,(2)

one of the ablest ecclesiastical dignitaries of his age, and certainly one of

the most formidable champions of the Cause. His father, Mulla Rahim-i-Zanjani,

was one of the leading mujtahids of Zanjan, and was greatly esteemed for his piety,

his learning and force of character. Mulla Muhammad-'Ali, surnamed Hujjat, was

born in the year 1227 A.H.(3)

From his very boyhood, he showed such capacity that his father lavished the utmost

care upon his education. He sent him to Najaf, where he distinguished himself

by his insight, his ability and fiery ardour.(4)

His scholarship and keen intelligence excited the admiration of his friends, whilst

his outspokenness and the strength of his character made him the terror of his

adversaries. His father advised him not to return to Zanjan,

I now proceed to relate the

circumstances that have made of that event one of the most thrilling episodes

in the history of this Revelation. Its chief figure was Hujjat-i-Zanjani, whose

name was Mulla Muhammad-'Ali,(2)

one of the ablest ecclesiastical dignitaries of his age, and certainly one of

the most formidable champions of the Cause. His father, Mulla Rahim-i-Zanjani,

was one of the leading mujtahids of Zanjan, and was greatly esteemed for his piety,

his learning and force of character. Mulla Muhammad-'Ali, surnamed Hujjat, was

born in the year 1227 A.H.(3)

From his very boyhood, he showed such capacity that his father lavished the utmost

care upon his education. He sent him to Najaf, where he distinguished himself

by his insight, his ability and fiery ardour.(4)

His scholarship and keen intelligence excited the admiration of his friends, whilst

his outspokenness and the strength of his character made him the terror of his

adversaries. His father advised him not to return to Zanjan,

530

where his enemies were conspiring

against him. He accordingly decided to establish his residence in Hamadan,(1)

where he married one of his kinswomen, and lived there for about two and a half

years, when the news of his father's death decided him to leave for his native

town. The ovation accorded him on his arrival inflamed the hostility of the ulamas,

who, despite their avowed opposition, received at his hands every mark of consideration

and kindness.(2)

From the pulpit of the masjid which his friends

erected in his honour, he urged the vast throng that gathered to hear him, to

refrain from self-indulgence and to exercise moderation in all their acts.(3)

He ruthlessly suppressed every form of abuse, and by his example encouraged the

people to adhere rigidly to the principles inculcated by the Qur'an. Such were

the care and ability with which he taught his disciples that they surpassed in

knowledge and understanding the recognised ulamas of Zanjan. For seventeen years,

he pursued his meritorious labours and succeeded in purging the minds and hearts

of his fellow-townsmen from whatever seemed contrary to the spirit and teachings

of their Faith.(4)

From the pulpit of the masjid which his friends

erected in his honour, he urged the vast throng that gathered to hear him, to

refrain from self-indulgence and to exercise moderation in all their acts.(3)

He ruthlessly suppressed every form of abuse, and by his example encouraged the

people to adhere rigidly to the principles inculcated by the Qur'an. Such were

the care and ability with which he taught his disciples that they surpassed in

knowledge and understanding the recognised ulamas of Zanjan. For seventeen years,

he pursued his meritorious labours and succeeded in purging the minds and hearts

of his fellow-townsmen from whatever seemed contrary to the spirit and teachings

of their Faith.(4)

When the Call from Shiraz reached him, he

despatched his trusted messenger, Mulla Iskandar, to enquire into the claims of

the new Revelation; and such was his response to

When the Call from Shiraz reached him, he

despatched his trusted messenger, Mulla Iskandar, to enquire into the claims of

the new Revelation; and such was his response to

531

that Message that his enemies

were stirred to redouble their attacks upon him. Unable, hitherto, to disgrace

him in the eyes of the government and the people, they now endeavoured to denounce

him as an advocate of heresy and a repudiator of all that is sacred and cherished

in Islam. "His reputation for justice, for piety, wisdom, and learning," they

whispered to one another, "has been such as to render it impossible for us to

shake his position. When summoned to Tihran, in the presence of Muhammad Shah

was he not able, by his magnetic eloquence, to win him over to his side, and make

of him one of his devoted admirers? Now, however, that he has so openly championed

the cause of the Siyyid-i-Bab, we can surely succeed in obtaining from the government

the order for his arrest and banishment from our town."

They accordingly drew up

a petition to Muhammad Shah, in which they sought, by every device their malevolent

and crafty minds could invent, to discredit his name. "While still professing

himself a follower of our Faith," they complained, "he, by the aid of his disciples,

was able to repudiate our authority. Now that he has identified himself with the

cause of the Siyyid-i-Bab and won over to that hateful creed two-thirds of the

inhabitants of Zanjan, what humiliation will he not inflict upon us! The concourse

that throngs his gates, the whole masjid can no longer contain. Such is his influence

that the masjid that belonged to his father and the one that has been built in

his honour, have been connected and made into one edifice in order to accommodate

the ever-increasing multitude that hastens eagerly to follow his lead in prayer.

The time is fast approaching when not only Zanjan but the neighbouring villages

also will have declared themselves his supporters."

They accordingly drew up

a petition to Muhammad Shah, in which they sought, by every device their malevolent

and crafty minds could invent, to discredit his name. "While still professing

himself a follower of our Faith," they complained, "he, by the aid of his disciples,

was able to repudiate our authority. Now that he has identified himself with the

cause of the Siyyid-i-Bab and won over to that hateful creed two-thirds of the

inhabitants of Zanjan, what humiliation will he not inflict upon us! The concourse

that throngs his gates, the whole masjid can no longer contain. Such is his influence

that the masjid that belonged to his father and the one that has been built in

his honour, have been connected and made into one edifice in order to accommodate

the ever-increasing multitude that hastens eagerly to follow his lead in prayer.

The time is fast approaching when not only Zanjan but the neighbouring villages

also will have declared themselves his supporters."

The Shah was greatly surprised at the tone

and language with which the petitioners sought to arraign Hujjat. He shared his

astonishment with Mirza Nazar-'Ali, the Hakim-Bashi, and recalled the glowing

tribute which many a visitor to Zanjan had paid to the abilities and integrity

of the accused. He decided to summon him, together with his opponents, to Tihran.

In a special gathering at which he himself, together with Haji Mirza Aqasi and

the leading officials of the government, as well as a number of the recognised

ulamas

The Shah was greatly surprised at the tone

and language with which the petitioners sought to arraign Hujjat. He shared his

astonishment with Mirza Nazar-'Ali, the Hakim-Bashi, and recalled the glowing

tribute which many a visitor to Zanjan had paid to the abilities and integrity

of the accused. He decided to summon him, together with his opponents, to Tihran.

In a special gathering at which he himself, together with Haji Mirza Aqasi and

the leading officials of the government, as well as a number of the recognised

ulamas

532

of Tihran, had assembled,

he called upon the ecclesiastical leaders of Zanjan to vindicate the claims they

had advanced. Whatever questions they submitted to Hujjat, regarding the teachings

of their Faith, he answered in a manner that could not fail to win the unqualified

admiration of his hearers and to establish the sovereign's confidence in his innocence.

The Shah expressed his entire satisfaction, and amply rewarded Hujjat for the

excellent manner in which he had succeeded in refuting the allegations of his

enemies. He bade him return to Zanjan and resume his valuable services to the

cause of his people, assuring him that he would under all circumstances support

him and asking to be informed of any difficulty with which he might be faced in

the future.(1)

His arrival at Zanjan was the signal for a

fierce outburst on the part of his humiliated opponents. As the evidences of their

hostility multiplied, the marks of devotion on the part of his friends and supporters

correspondingly increased.(2)

Utterly disdainful of their machinations, he pursued his activities with unrelaxing

zeal.(3) The liberal principles

which he unceasingly and fearlessly advocated struck at the very root of the fabric

which a bigoted enemy had laboriously reared. They beheld with impotent fury the

disruption of their authority and the collapse of their institutions.

His arrival at Zanjan was the signal for a

fierce outburst on the part of his humiliated opponents. As the evidences of their

hostility multiplied, the marks of devotion on the part of his friends and supporters

correspondingly increased.(2)

Utterly disdainful of their machinations, he pursued his activities with unrelaxing

zeal.(3) The liberal principles

which he unceasingly and fearlessly advocated struck at the very root of the fabric

which a bigoted enemy had laboriously reared. They beheld with impotent fury the

disruption of their authority and the collapse of their institutions.

It was in those days that his special envoy,

Mashhadi Ahmad, whom he had confidentially despatched to Shiraz with a petition

and gifts from him to the Bab, arrived at

It was in those days that his special envoy,

Mashhadi Ahmad, whom he had confidentially despatched to Shiraz with a petition

and gifts from him to the Bab, arrived at

533

Zanjan and delivered into

his hands, while he was addressing his disciples, a sealed letter from his Beloved.

In the Tablet he received, the Bab conferred upon him one of His own titles, that

of Hujjat, and urged him to proclaim from the pulpit, without the least reservation,

the fundamental teachings of His Faith. No sooner was he informed of the wishes

of his Master than he declared his resolve to devote himself to the immediate

enforcement of whatever injunction that Tablet contained. He immediately dismissed

his disciples, bade them close their books, and declared his intention of discontinuing

his courses of study. "Of what profit," he said, "are study and research to those

who have already found the Truth, and why strive after learning when He who is

the Object of all knowledge is made manifest?"

As soon as he attempted to lead the congregation

in offering the Friday prayer, enjoined upon him by the Bab,(1)

the Imam-Jum'ih, who had hitherto performed that duty, vehemently protested, on

the ground that this right was the exclusive privilege of his own forefathers,

that it had been conferred upon him by his sovereign, and that no one, however

exalted his station, could usurp it. "That right," Hujjat retorted, "has been

superseded by the authority with which the Qa'im Himself has invested me. I have

been commanded by Him to assume that function publicly, and I cannot allow any

person to trespass upon that right. If attacked, I will take steps to defend myself

and to protect the lives of my companions."

As soon as he attempted to lead the congregation

in offering the Friday prayer, enjoined upon him by the Bab,(1)

the Imam-Jum'ih, who had hitherto performed that duty, vehemently protested, on

the ground that this right was the exclusive privilege of his own forefathers,

that it had been conferred upon him by his sovereign, and that no one, however

exalted his station, could usurp it. "That right," Hujjat retorted, "has been

superseded by the authority with which the Qa'im Himself has invested me. I have

been commanded by Him to assume that function publicly, and I cannot allow any

person to trespass upon that right. If attacked, I will take steps to defend myself

and to protect the lives of my companions."

His fearless insistence on the duty laid upon

him by the Bab caused the ulamas of Zanjan to league themselves with the Imam-Jum'ih(2)

and to lay their complaints before Haji Mirza Aqasi, pleading that Hujjat had

challenged the validity

His fearless insistence on the duty laid upon

him by the Bab caused the ulamas of Zanjan to league themselves with the Imam-Jum'ih(2)

and to lay their complaints before Haji Mirza Aqasi, pleading that Hujjat had

challenged the validity

534

of recognised institutions

and trampled upon their rights. "We must either flee from this town with our families

and belongings," they pleaded, "and leave him in sole charge of the destinies

of its people, or obtain from Muhammad Shah an edict for his immediate expulsion

from this country; for we firmly believe that to allow him to remain on its soil

would be courting disaster." Though Haji Mirza Aqasi, in his heart, distrusted

the ecclesiastical order of his country and had a natural aversion to their beliefs

and practices, he was forced eventually to yield to their pressing demands, and

submitted the matter to Muhammad Shah, who ordered the transfer of Hujjat from

Zanjan to the capital.

A Kurd named Qilij Khan was commissioned by

the Shah to deliver the royal summons to Hujjat. The Bab had meanwhile arrived

in the neighbourhood of Tihran on His way to Tabriz. Ere the arrival of the royal

messenger at Zanjan, Hujjat had sent one of his friends, a certain Khan-Muhammad-i-Tub-Chi,

to his Master with a petition in which he begged to be allowed to rescue Him from

the hands of the enemy. The Bab assured him that His deliverance the Almighty

alone could achieve and that no one could escape from His decree or evade His

law. "As to your meeting with Me," He added, "it soon will take place in the world

beyond, the home of unfading glory."

A Kurd named Qilij Khan was commissioned by

the Shah to deliver the royal summons to Hujjat. The Bab had meanwhile arrived

in the neighbourhood of Tihran on His way to Tabriz. Ere the arrival of the royal

messenger at Zanjan, Hujjat had sent one of his friends, a certain Khan-Muhammad-i-Tub-Chi,

to his Master with a petition in which he begged to be allowed to rescue Him from

the hands of the enemy. The Bab assured him that His deliverance the Almighty

alone could achieve and that no one could escape from His decree or evade His

law. "As to your meeting with Me," He added, "it soon will take place in the world

beyond, the home of unfading glory."

The day Hujjat received that

message, Qilij Khan arrived at Zanjan, acquainted him with the orders he had received,

and set out, accompanied by him, for the capital. Their arrival at Tihran coincided

with the Bab's departure from the village of Kulayn, where He had been detained

for some days.

The day Hujjat received that

message, Qilij Khan arrived at Zanjan, acquainted him with the orders he had received,

and set out, accompanied by him, for the capital. Their arrival at Tihran coincided

with the Bab's departure from the village of Kulayn, where He had been detained

for some days.

The authorities, apprehensive lest a meeting

between the Bab and Hujjat might lead to fresh disturbances, had taken the necessary

precautions to ensure the absence of the latter from Zanjan during the Bab's passage

through that town. The companions who were following Hujjat at a distance, whilst

he was on his way to the capital, were urged by him to return and try to meet

their Master and to assure Him of his readiness to come to His rescue. On their

way back to their homes, they encountered the Bab, who again expressed His desire

that no one of His friends should attempt to

The authorities, apprehensive lest a meeting

between the Bab and Hujjat might lead to fresh disturbances, had taken the necessary

precautions to ensure the absence of the latter from Zanjan during the Bab's passage

through that town. The companions who were following Hujjat at a distance, whilst

he was on his way to the capital, were urged by him to return and try to meet

their Master and to assure Him of his readiness to come to His rescue. On their

way back to their homes, they encountered the Bab, who again expressed His desire

that no one of His friends should attempt to

535

deliver Him from His captivity.

He even directed them to tell the believers among their fellow-townsmen not to

press round Him, but even to avoid Him wherever He went.

No sooner had that message been delivered

to those who had gone out to welcome Him on His approach to their town

No sooner had that message been delivered

to those who had gone out to welcome Him on His approach to their town

than they began to grieve

and deplore their fate. They could not, however, resist the impulse that drove

them to march forth to meet Him, forgetful of the desire He had expressed.

than they began to grieve

and deplore their fate. They could not, however, resist the impulse that drove

them to march forth to meet Him, forgetful of the desire He had expressed.

As soon as they were met by the guards who

were marching in advance of their Captive, they were ruthlessly dispersed. On

reaching a fork in the road, there arose an altercation

As soon as they were met by the guards who

were marching in advance of their Captive, they were ruthlessly dispersed. On

reaching a fork in the road, there arose an altercation

536

between Muhammad Big-i-Chaparchi

and his colleague, who had been despatched from Tihran to assist in conducting

the Bab to Tabriz. Muhammad Big insisted that their Prisoner should be taken into

the town, where He should be allowed to pass the night in the caravanserai of

Mirza Ma'sum-i-Tabib, the father of Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Tabib, a martyr of

the Faith, before resuming their march to Adhirbayjan. He pleaded that to pass

the night outside the gate would be to expose their lives to danger, and would

encourage their opponents to attempt an attack upon them. He eventually succeeded

in convincing his colleague that he should conduct the Bab to that caravanserai.

As they were passing through the streets, they were amazed to see the multitude

that had crowded onto the housetops in their eagerness to catch a glimpse of the

face of the Prisoner.

Mirza Ma'sum, the former owner of the caravanserai,

had lately died, and his eldest son, Mirza Muhammad-'Ali, the leading physician

of Hamadan, who, though not a believer, was a true lover of the Bab, had arrived

at Zanjan and was in mourning for his father. He lovingly received the Bab in

the caravanserai he had specially prepared beforehand for His reception. That

night he remained until a late hour in His presence and was completely won over

to His Cause.

Mirza Ma'sum, the former owner of the caravanserai,

had lately died, and his eldest son, Mirza Muhammad-'Ali, the leading physician

of Hamadan, who, though not a believer, was a true lover of the Bab, had arrived

at Zanjan and was in mourning for his father. He lovingly received the Bab in

the caravanserai he had specially prepared beforehand for His reception. That

night he remained until a late hour in His presence and was completely won over

to His Cause.

"The same night that witnessed my conversion,"

I heard him subsequently relate, "I arose ere break of day, lit my lantern, and,

preceded by my father's attendant, directed my steps towards the caravanserai.

The guards who were stationed at the entrance recognised me and allowed me to

enter. The Bab was performing His ablutions when I was ushered into His presence.

I was greatly impressed when I saw Him absorbed in His devotions. A feeling of

reverent joy filled my heart as I stood behind Him and prayed. I myself prepared

His tea and was offering it to Him when He turned to me and bade me depart for

Hamadan. `This town,' He said, `will be thrown into a great tumult, and its streets

will run with blood.' I expressed my strong desire to be allowed to shed my blood

in His path. He assured me that the hour of my martyrdom had not yet come, and

bade me be resigned to whatever God might decree. At the hour

"The same night that witnessed my conversion,"

I heard him subsequently relate, "I arose ere break of day, lit my lantern, and,

preceded by my father's attendant, directed my steps towards the caravanserai.

The guards who were stationed at the entrance recognised me and allowed me to

enter. The Bab was performing His ablutions when I was ushered into His presence.

I was greatly impressed when I saw Him absorbed in His devotions. A feeling of

reverent joy filled my heart as I stood behind Him and prayed. I myself prepared

His tea and was offering it to Him when He turned to me and bade me depart for

Hamadan. `This town,' He said, `will be thrown into a great tumult, and its streets

will run with blood.' I expressed my strong desire to be allowed to shed my blood

in His path. He assured me that the hour of my martyrdom had not yet come, and

bade me be resigned to whatever God might decree. At the hour

537

of sunrise, as He mounted

His horse and was preparing to depart, I begged to be allowed to follow Him, but

He advised me to remain, and assured me of His unfailing prayers. Resigning myself

to His will, with regret I watched Him disappear from my sight."

On his arrival at Tihran,

Hujjat was conducted into the presence of Haji Mirza Aqasi; who, on behalf of

the Shah and himself, expressed his annoyance at the intense hostility which his

conduct had aroused among the ulamas of Zanjan. "Muhammad Shah and I," he told

him, "are continually besieged by the oral as well as written denunciations brought

against you. I could scarcely believe their indictment relating to your desertion

of the Faith of your forefathers. Nor is the Shah inclined to credit such assertions.

I have been commanded by him to summon you to his capital and to call upon you

to refute such accusations. It grieves me to hear that a man whom I consider infinitely

superior in knowledge and ability to the Siyyid-i-Bab has chosen to identify himself

with his creed." "Not so," replied Hujjat; "God knows that if that same Siyyid

were to entrust me with the meanest service in His household, I would deem it

an honour such as the highest favours of my sovereign could never hope to surpass."

"This can never be!" burst forth Haji Mirza Aqasi. "It is my firm and unalterable

conviction," Hujjat reaffirmed, "that this Siyyid of Shiraz is the very One whose

advent you yourself, with all the peoples of the world, are eagerly awaiting.

He is our Lord, our promised Deliverer.

On his arrival at Tihran,

Hujjat was conducted into the presence of Haji Mirza Aqasi; who, on behalf of

the Shah and himself, expressed his annoyance at the intense hostility which his

conduct had aroused among the ulamas of Zanjan. "Muhammad Shah and I," he told

him, "are continually besieged by the oral as well as written denunciations brought

against you. I could scarcely believe their indictment relating to your desertion

of the Faith of your forefathers. Nor is the Shah inclined to credit such assertions.

I have been commanded by him to summon you to his capital and to call upon you

to refute such accusations. It grieves me to hear that a man whom I consider infinitely

superior in knowledge and ability to the Siyyid-i-Bab has chosen to identify himself

with his creed." "Not so," replied Hujjat; "God knows that if that same Siyyid

were to entrust me with the meanest service in His household, I would deem it

an honour such as the highest favours of my sovereign could never hope to surpass."

"This can never be!" burst forth Haji Mirza Aqasi. "It is my firm and unalterable

conviction," Hujjat reaffirmed, "that this Siyyid of Shiraz is the very One whose

advent you yourself, with all the peoples of the world, are eagerly awaiting.

He is our Lord, our promised Deliverer.

Haji Mirza Aqasi reported the matter to Muhammad

Shah, to whom he expressed his fears that to allow so formidable an adversary,

whom the sovereign himself believed to be the most accomplished of the ulamas

of his realm, to pursue unhindered the course of his activities would be a policy

fraught with gravest danger to the State. The Shah, disinclined to credit such

reports, which he attributed to the malice and envy of the enemies of the accused,

ordered that a special meeting be convened at which he should be asked to vindicate

his position in the presence of the assembled ulamas of the capital.

Haji Mirza Aqasi reported the matter to Muhammad

Shah, to whom he expressed his fears that to allow so formidable an adversary,

whom the sovereign himself believed to be the most accomplished of the ulamas

of his realm, to pursue unhindered the course of his activities would be a policy

fraught with gravest danger to the State. The Shah, disinclined to credit such

reports, which he attributed to the malice and envy of the enemies of the accused,

ordered that a special meeting be convened at which he should be asked to vindicate

his position in the presence of the assembled ulamas of the capital.

Several meetings were held for that purpose,

before each

Several meetings were held for that purpose,

before each

538

of which Hujjat eloquently

set forth the basic claims of his Faith and confounded the arguments of those

who tried to oppose him. "Is not the following tradition," he boldly declared,

"recognised alike by shi'ah and sunni Islam: `I leave amidst you my twin testimonies,

the Book of God and my family'? Has not the second of these testimonies, in your

opinion, passed away, and is not our sole means of guidance, as a result, contained

in the testimony of the sacred Book? I appeal to you to measure every claim that

either of us shall advance, by the standard established in that Book, and to regard

it as the supreme authority whereby the righteousness of our argument can be judged."

Unable to defend their case against him, they, as a last resort, ventured to ask

him to produce a miracle whereby to establish the truth of his assertion. "What

greater miracle," he exclaimed, "than that He should have enabled me to triumph,

alone and unaided, by the simple power of my argument, over the combined forces

of the mujtahids and ulamas of Tihran?"

The masterly manner in which Hujjat refuted

the unsound claims advanced by his adversaries won for him the favour of his sovereign,

who from that day forth was no longer swayed by the insinuations of his enemies.

Although the entire company of the ulamas of Zanjan, as well as a number of the

ecclesiastical leaders of Tihran, had declared him to be an infidel and condemned

him to death, yet Muhammad Shah continued to bestow his favours upon him and to

assure him that he could rely on his support. Haji Mirza Aqasi, though at heart

unfriendly to Hujjat, was unable, in the face of such unmistakable evidences of

royal favour, to resist his influence openly, and by his frequent visits to his

house, and by the gifts he lavished upon him, that deceitful minister sought to

conceal his resentment and envy.

The masterly manner in which Hujjat refuted

the unsound claims advanced by his adversaries won for him the favour of his sovereign,

who from that day forth was no longer swayed by the insinuations of his enemies.

Although the entire company of the ulamas of Zanjan, as well as a number of the

ecclesiastical leaders of Tihran, had declared him to be an infidel and condemned

him to death, yet Muhammad Shah continued to bestow his favours upon him and to

assure him that he could rely on his support. Haji Mirza Aqasi, though at heart

unfriendly to Hujjat, was unable, in the face of such unmistakable evidences of

royal favour, to resist his influence openly, and by his frequent visits to his

house, and by the gifts he lavished upon him, that deceitful minister sought to

conceal his resentment and envy.

Hujjat was virtually a prisoner in Tihran.

He was unable to go beyond the gates of the capital, nor was he allowed free intercourse

with his friends. The believers among his fellow-townsmen eventually determined

to send a deputation and ask him for fresh instructions regarding their attitude

towards the laws and principles of their Faith. He charged them to observe with

absolute loyalty the admonitions he had received from the Bab through the messengers

he had

Hujjat was virtually a prisoner in Tihran.

He was unable to go beyond the gates of the capital, nor was he allowed free intercourse

with his friends. The believers among his fellow-townsmen eventually determined

to send a deputation and ask him for fresh instructions regarding their attitude

towards the laws and principles of their Faith. He charged them to observe with

absolute loyalty the admonitions he had received from the Bab through the messengers

he had

539

sent to investigate His Cause.

He enumerated a series of observances, some of which constituted a definite departure

from the established traditions of Islam. "Siyyid Kazim-i-Zanjani," he assured

them, "has been intimately connected with my Master both in Shiraz and in Isfahan.

He, as well as Mulla Iskandar and Mashhadi Ahmad, both of whom I sent to meet

Him, have positively declared that He Himself is the first to practise the observances

He has enjoined upon the faithful. It therefore behoves us who are His supporters

to follow His noble example."

These explicit instructions were no sooner

read to his companions than they became inflamed with an irresistible desire to

carry out his wishes. They enthusiastically set to work to enforce the laws of

the new Dispensation, and, giving up their former customs and practices, unhesitatingly

identified themselves with its claims. Even the little children were encouraged

to follow scrupulously the admonitions of the Bab. "Our beloved Master," they

were taught to say, "Himself is the first to practise them. Why should we who

are His privileged disciples hesitate to make them the ruling principles of our

lives?"

These explicit instructions were no sooner

read to his companions than they became inflamed with an irresistible desire to

carry out his wishes. They enthusiastically set to work to enforce the laws of

the new Dispensation, and, giving up their former customs and practices, unhesitatingly

identified themselves with its claims. Even the little children were encouraged

to follow scrupulously the admonitions of the Bab. "Our beloved Master," they

were taught to say, "Himself is the first to practise them. Why should we who

are His privileged disciples hesitate to make them the ruling principles of our

lives?"

Hujjat was still a captive in Tihran when

the news of the siege of the fort of Tabarsi reached him. He longed, and deplored

his inability, to throw in his lot with those of his companions who were struggling

with such splendid heroism for the emancipation of their Faith. His sole consolation

in those days was his close association with Baha'u'llah, from whom he received

the sustaining power that enabled him, in the time to come, to distinguish himself

by deeds no less remarkable than those which that company had manifested in the

darkest hours of their memorable struggle.

Hujjat was still a captive in Tihran when

the news of the siege of the fort of Tabarsi reached him. He longed, and deplored

his inability, to throw in his lot with those of his companions who were struggling

with such splendid heroism for the emancipation of their Faith. His sole consolation

in those days was his close association with Baha'u'llah, from whom he received

the sustaining power that enabled him, in the time to come, to distinguish himself

by deeds no less remarkable than those which that company had manifested in the

darkest hours of their memorable struggle.

He was still in Tihran when

Muhammad Shah passed away, leaving the throne to his son Nasiri'd-Din Shah.(1)

The Amir-Nizam, the new Grand Vazir, decided to make Hujjat's imprisonment more

rigorous, and to seek in the meantime a way of destroying him. On being informed

of the imminence of the danger that threatened his life, his captive decided to

He was still in Tihran when

Muhammad Shah passed away, leaving the throne to his son Nasiri'd-Din Shah.(1)

The Amir-Nizam, the new Grand Vazir, decided to make Hujjat's imprisonment more

rigorous, and to seek in the meantime a way of destroying him. On being informed

of the imminence of the danger that threatened his life, his captive decided to

540

leave Tihran in disguise

and join his companions, who eagerly awaited his return.

His arrival at his native

town, which a certain Karbila'i Vali-'Attar announced to his companions, was a

signal for a tremendous demonstration of devoted loyalty on the part of his many

admirers. They flocked out, men, women, and children, to welcome him and to renew

their assurances of abiding and undiminished affection.(1)

The governor of Zanjan, Majdu'd-Dawlih,(2)

the maternal uncle of Nasiri'd-Din Shah, astounded by the spontaneity of that

ovation, ordered, in the fury of his despair, that the tongue of Karbila'i Vali-'Attar

be immediately cut out. Though at heart he loathed Hujjat, he pretended to be

his friend and well-wisher. He often visited him and showed him unbounded consideration,

yet he was secretly conspiring against his life and was waiting for the moment

when he could strike the fatal blow.

His arrival at his native

town, which a certain Karbila'i Vali-'Attar announced to his companions, was a

signal for a tremendous demonstration of devoted loyalty on the part of his many

admirers. They flocked out, men, women, and children, to welcome him and to renew

their assurances of abiding and undiminished affection.(1)

The governor of Zanjan, Majdu'd-Dawlih,(2)

the maternal uncle of Nasiri'd-Din Shah, astounded by the spontaneity of that

ovation, ordered, in the fury of his despair, that the tongue of Karbila'i Vali-'Attar

be immediately cut out. Though at heart he loathed Hujjat, he pretended to be

his friend and well-wisher. He often visited him and showed him unbounded consideration,

yet he was secretly conspiring against his life and was waiting for the moment

when he could strike the fatal blow.

That smouldering hostility was soon to be

fanned into flame by an incident that was of little importance in itself. The

occasion was afforded when a quarrel suddenly broke out between two children of

Zanjan, one of whom belonged to a kinsman of one of the companions of Hujjat.

The governor immediately ordered that child to be arrested and placed in strict

confinement. A sum of money was offered

That smouldering hostility was soon to be

fanned into flame by an incident that was of little importance in itself. The

occasion was afforded when a quarrel suddenly broke out between two children of

Zanjan, one of whom belonged to a kinsman of one of the companions of Hujjat.

The governor immediately ordered that child to be arrested and placed in strict

confinement. A sum of money was offered

541

by the believers to the governor,

in order to induce him to release his young prisoner. He refused their offer,

whereupon they complained to Hujjat, who vehemently protested. "That child," he

wrote to the governor, "is too young to be held responsible for his behaviour.

If he deserves punishment, his father and not he should be made to suffer."

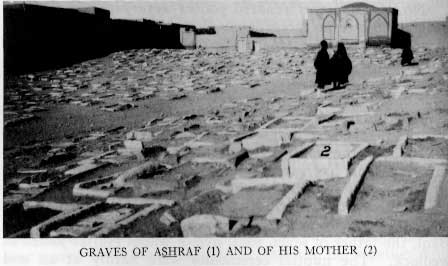

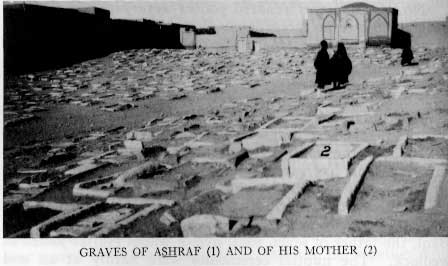

Finding that the appeal had been ignored,

he renewed his protest and entrusted it to the hands of one of his influential

comrades, Mir Jalil, father of Siyyid Ashraf and martyr of the Faith, directing

him to present it in person to the governor. The guards stationed at the entrance

of the house at first refused him admittance. Indignant at their refusal, he threatened

to force his way through the gate, and succeeded, by the mere threat of unsheathing

his sword, in overcoming their resistance and in compelling the infuriated governor

to release the child.

Finding that the appeal had been ignored,

he renewed his protest and entrusted it to the hands of one of his influential

comrades, Mir Jalil, father of Siyyid Ashraf and martyr of the Faith, directing

him to present it in person to the governor. The guards stationed at the entrance

of the house at first refused him admittance. Indignant at their refusal, he threatened

to force his way through the gate, and succeeded, by the mere threat of unsheathing

his sword, in overcoming their resistance and in compelling the infuriated governor

to release the child.

The unconditional compliance of the governor

with the demand of Mir Jalil stirred the furious indignation of the ulamas. They

violently protested, and deprecated his submission to the threats with which their

opponents had sought to intimidate him. They expressed to him their fear that

such a surrender on his part would encourage them to make still greater demands

upon him, would enable them before long to assume the reins of authority and to

exclude him from any share in the administration of the government. They eventually

induced him to consent to the arrest of Hujjat, an act which they were convinced

would succeed in checking the progress of his influence.

The unconditional compliance of the governor

with the demand of Mir Jalil stirred the furious indignation of the ulamas. They

violently protested, and deprecated his submission to the threats with which their

opponents had sought to intimidate him. They expressed to him their fear that

such a surrender on his part would encourage them to make still greater demands

upon him, would enable them before long to assume the reins of authority and to

exclude him from any share in the administration of the government. They eventually

induced him to consent to the arrest of Hujjat, an act which they were convinced

would succeed in checking the progress of his influence.

The governor reluctantly consented. He was

repeatedly assured by the ulamas that his action would under no circumstances

endanger the peace and security of the town. Two of their supporters, Pahlavan(1)

Asadu'llah and Pahlavan Safar-'Ali, both notorious for their brutality and prodigious

strength, volunteered to seize Hujjat and deliver him hand-cuffed to the governor.

Each was promised a handsome reward in return for this service. Clad in their

amour, with helmets on their heads, and followed by a band of ruffians recruited

from among the most degraded of the population.

The governor reluctantly consented. He was

repeatedly assured by the ulamas that his action would under no circumstances

endanger the peace and security of the town. Two of their supporters, Pahlavan(1)

Asadu'llah and Pahlavan Safar-'Ali, both notorious for their brutality and prodigious

strength, volunteered to seize Hujjat and deliver him hand-cuffed to the governor.

Each was promised a handsome reward in return for this service. Clad in their

amour, with helmets on their heads, and followed by a band of ruffians recruited

from among the most degraded of the population.

542

they set out to accomplish

their purpose. The ulamas were in the meantime busily engaged in inciting the

populace and encouraging them to reinforce their efforts.

As soon as the emissaries arrived in the quarter

in which Hujjat was living, they were unexpectedly confronted by Mir Salah, one

of his most formidable supporters, who, together with seven of his armed companions,

strenuously opposed their advance. He asked Asadu'llah whither he was bound, and,

on receiving from him an insulting answer, unsheathed his sword and, with the

cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!"(1)

sprang upon him and wounded him in the forehead. Mir Salah's audacity, in spite

of the heavy amour which his adversary was wearing, frightened the whole band

and caused them to flee in different directions.(2)

As soon as the emissaries arrived in the quarter

in which Hujjat was living, they were unexpectedly confronted by Mir Salah, one

of his most formidable supporters, who, together with seven of his armed companions,

strenuously opposed their advance. He asked Asadu'llah whither he was bound, and,

on receiving from him an insulting answer, unsheathed his sword and, with the

cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!"(1)

sprang upon him and wounded him in the forehead. Mir Salah's audacity, in spite

of the heavy amour which his adversary was wearing, frightened the whole band

and caused them to flee in different directions.(2)

The cry which that stout-hearted defender

of the Faith raised on that day was heard for the first time in Zanjan, a cry

that spread panic through the town. The governor was terrified by its tremendous

force, and asked what that shout could mean and whose voice had been able to raise

it. He was gravely shaken when told that it was the watchword of Hujjat's companions,

with which they called for the assistance of the Qa'im in the hour of distress.

The cry which that stout-hearted defender

of the Faith raised on that day was heard for the first time in Zanjan, a cry

that spread panic through the town. The governor was terrified by its tremendous

force, and asked what that shout could mean and whose voice had been able to raise

it. He was gravely shaken when told that it was the watchword of Hujjat's companions,

with which they called for the assistance of the Qa'im in the hour of distress.

The remnants of that affrighted band encountered,

shortly after, Shaykh Muhammad-i-Tub-Chi, whom they immediately recognised as

one of their ablest adversaries. Finding him unarmed, they fell upon him and,

with an axe one of them was carrying, struck him and broke his head. They bore

him to the governor, and no sooner had they laid down the wounded man than a certain

Siyyid Abu'l-Qasim, one of the mujtahids of Zanjan who was present, leaped forward

and, with his penknife, stabbed him in the breast. The governor too, unsheathing

his sword, struck him on the mouth and was followed by the attendants who, with

the weapons they carried with them, completed the murder of their hapless victim.

As their blows rained upon him, unmindful of his sufferings, he was heard to say:

"I thank Thee, O my God, for having vouchsafed me the crown of martyrdom."

The remnants of that affrighted band encountered,

shortly after, Shaykh Muhammad-i-Tub-Chi, whom they immediately recognised as

one of their ablest adversaries. Finding him unarmed, they fell upon him and,

with an axe one of them was carrying, struck him and broke his head. They bore

him to the governor, and no sooner had they laid down the wounded man than a certain

Siyyid Abu'l-Qasim, one of the mujtahids of Zanjan who was present, leaped forward

and, with his penknife, stabbed him in the breast. The governor too, unsheathing

his sword, struck him on the mouth and was followed by the attendants who, with

the weapons they carried with them, completed the murder of their hapless victim.

As their blows rained upon him, unmindful of his sufferings, he was heard to say:

"I thank Thee, O my God, for having vouchsafed me the crown of martyrdom."

543

He was the first among the

believers of Zanjan to lay down his life in the path of the Cause. His death,

which occurred on Friday, the fourth of Rajab, in the year 1266 A.H.,(1)

preceded by forty-five days the martyrdom of Vahid and by fifty-five days that

of the Bab.

The blood that was shed on

that day, far from allaying the hostility of the enemy, served further to inflame

their passions, and to reinforce their determination to subject to the same fate

the rest of the companions. Encouraged by the governor's tacit approval of their

expressed intentions, they resolved to put to death all upon whom they could lay

their hands, without obtaining beforehand an express authorisation from the government

officials. They solemnly covenanted among themselves not to rest until they had

extinguished the fire of what they deemed a shameless heresy.(2)

They compelled the governor to bid a crier proclaim throughout Zanjan that whoever

was willing to endanger his life, to forfeit his property, and expose his wife

and children to misery and shame, should throw in his lot with Hujjat and his

companions; and that those desirous of ensuring the well-being and honour of themselves

and their families, should withdraw from the neighbourhood in which those companions

resided and seek the shelter of the sovereign's protection.

The blood that was shed on

that day, far from allaying the hostility of the enemy, served further to inflame

their passions, and to reinforce their determination to subject to the same fate

the rest of the companions. Encouraged by the governor's tacit approval of their

expressed intentions, they resolved to put to death all upon whom they could lay

their hands, without obtaining beforehand an express authorisation from the government

officials. They solemnly covenanted among themselves not to rest until they had

extinguished the fire of what they deemed a shameless heresy.(2)

They compelled the governor to bid a crier proclaim throughout Zanjan that whoever

was willing to endanger his life, to forfeit his property, and expose his wife

and children to misery and shame, should throw in his lot with Hujjat and his

companions; and that those desirous of ensuring the well-being and honour of themselves

and their families, should withdraw from the neighbourhood in which those companions

resided and seek the shelter of the sovereign's protection.

That warning immediately divided the inhabitants

into two distinct camps, and severely tested the faith of those who were still

wavering in their allegiance to the Cause. It gave rise to the most pathetic scenes,

caused the separation of fathers from their sons and the estrangement of brothers

and of kindred. Every tie of worldly affection seemed to be dissolving on that

day, and the solemn pledges were forsaken in favour of a loyalty mightier and

more sacred than any earthly allegiance. Zanjan fell a prey to the wildest excitement.

The cry of distress which members of divided families, in a frenzy of despair,

raised to heaven, mingled with the blasphemous shouts which a threatening enemy

That warning immediately divided the inhabitants

into two distinct camps, and severely tested the faith of those who were still

wavering in their allegiance to the Cause. It gave rise to the most pathetic scenes,

caused the separation of fathers from their sons and the estrangement of brothers

and of kindred. Every tie of worldly affection seemed to be dissolving on that

day, and the solemn pledges were forsaken in favour of a loyalty mightier and

more sacred than any earthly allegiance. Zanjan fell a prey to the wildest excitement.

The cry of distress which members of divided families, in a frenzy of despair,

raised to heaven, mingled with the blasphemous shouts which a threatening enemy

544

hurled upon them. Shouts

of exultation hailed at every turn those who, tearing themselves from their homes

and kinsmen, enrolled themselves as willing supporters of the Cause of Hujjat.

The camp of the enemy hummed with feverish activity in preparation for the great

struggle upon which they had secretly determined. Reinforcements were rushed into

the town from the neighbouring villages, at the command of its governor and with

the encouragement of the mujtahids, the siyyids, and the ulamas who supported

him.(1)

Undeterred by the growing tumult, Hujjat ascended

the pulpit and, with uplifted voice, proclaimed to the congregation: "The hand

of Omnipotence has, in this day, separated truth from falsehood and divided the

light of guidance from the darkness of error. I am unwilling that because of me

you should suffer injury. The one aim of the governor and of the ulamas who support

him is to seize and kill me. They cherish no other ambition. They thirst for my

blood and seek no one besides me. Whoever among you feels the least desire to

safeguard his life against the perils with which we are beset, whoever is reluctant

to offer his life for our Cause, let him, ere it is too late, betake himself from

this place and return whence he came."(2)

Undeterred by the growing tumult, Hujjat ascended

the pulpit and, with uplifted voice, proclaimed to the congregation: "The hand

of Omnipotence has, in this day, separated truth from falsehood and divided the

light of guidance from the darkness of error. I am unwilling that because of me

you should suffer injury. The one aim of the governor and of the ulamas who support

him is to seize and kill me. They cherish no other ambition. They thirst for my

blood and seek no one besides me. Whoever among you feels the least desire to

safeguard his life against the perils with which we are beset, whoever is reluctant

to offer his life for our Cause, let him, ere it is too late, betake himself from

this place and return whence he came."(2)

That day more than three thousand men were

recruited by the governor from the surrounding villages of Zanjan. Meanwhile Mir

Salah, accompanied by a number of his comrades, who observed the growing restiveness

of their

That day more than three thousand men were

recruited by the governor from the surrounding villages of Zanjan. Meanwhile Mir

Salah, accompanied by a number of his comrades, who observed the growing restiveness

of their

545

opponents, sought the presence

of Hujjat and urged him, as a precautionary measure, to transfer his residence

to the fort of Ali-Mardan Khan,(1)

adjacent to the quarter in which he was residing. Hujjat gave his consent and

ordered that their women and children, together with such provisions as they might

require, be taken to the fort. Though they found it occupied by its owners, the

companions eventually induced them to withdraw, and gave them in exchange the

houses in which they themselves had been dwelling.

The enemy was meanwhile preparing for a violent

attack upon them. No sooner had a detachment of their forces opened fire upon

the barricades the companions had raised than Mir Rida, a siyyid of exceptional

courage, asked his leader to allow him to attempt to capture the governor and

to bring him as a prisoner to the fort. Hujjat, unwilling to comply with his request,

advised him not to risk his life.

The enemy was meanwhile preparing for a violent

attack upon them. No sooner had a detachment of their forces opened fire upon

the barricades the companions had raised than Mir Rida, a siyyid of exceptional

courage, asked his leader to allow him to attempt to capture the governor and

to bring him as a prisoner to the fort. Hujjat, unwilling to comply with his request,

advised him not to risk his life.

The governor was so overcome

with fear when informed of that siyyid's intention that he decided to leave Zanjan

immediately. He was, however, dissuaded from taking that course by a certain siyyid

who pleaded that his departure would be the signal for grave disturbances such

as would disgrace him in the sight of his superiors. The siyyid himself

The governor was so overcome

with fear when informed of that siyyid's intention that he decided to leave Zanjan

immediately. He was, however, dissuaded from taking that course by a certain siyyid

who pleaded that his departure would be the signal for grave disturbances such

as would disgrace him in the sight of his superiors. The siyyid himself

546

set out, as evidence of his

earnestness, to launch an offensive against the occupants of the fort. He had

no sooner given the signal for attack and advanced at the head of a band of thirty

of his comrades, than he unexpectedly encountered two of his adversaries who were

marching with drawn swords towards him. Believing that they intended to assail

him, he, with the whole of his band, was suddenly seized with panic, straightway

regained his home, and, forgetful of the assurances he had given to the governor,

remained the whole day closeted within his room. Those who were with him promptly

dispersed, renouncing the thought of pursuing the attack. They were subsequently

informed that the two men they had encountered had no hostile intention against

them, but were simply on their way to fulfil a commission with which they had

been entrusted.

That humiliating episode was soon followed

by a number of similar attempts on the part of the supporters of the governor,

all of which utterly failed to achieve their purpose. Every time they rushed to

attack the fort, Hujjat would order a few of his companions, who were three thousand

in number, to emerge from their retreat and scatter their forces. He

never failed, every time he gave them such orders, to caution his fellow-disciples

against shedding unnecessarily the blood of their assailants. He constantly reminded

them that their action was of a purely defensive character, and that their sole

purpose was to preserve inviolate the security of their women and children. "We

are commanded," he was frequently heard to observe, "not to wage holy war under

any circumstances against the unbelievers, whatever be their attitude towards

us."

That humiliating episode was soon followed

by a number of similar attempts on the part of the supporters of the governor,

all of which utterly failed to achieve their purpose. Every time they rushed to

attack the fort, Hujjat would order a few of his companions, who were three thousand

in number, to emerge from their retreat and scatter their forces. He

never failed, every time he gave them such orders, to caution his fellow-disciples

against shedding unnecessarily the blood of their assailants. He constantly reminded

them that their action was of a purely defensive character, and that their sole

purpose was to preserve inviolate the security of their women and children. "We

are commanded," he was frequently heard to observe, "not to wage holy war under

any circumstances against the unbelievers, whatever be their attitude towards

us."

This state of affairs continued(1)

until the orders of the

This state of affairs continued(1)

until the orders of the

547

Amir-Nizam reached one of

the generals of the imperial army, Sadru'd-Dawliy-i-Isfahani by name,(1)

who had set out at the head of two regiments for Adhirbayjan. The written orders

of the Grand Vazir reached him in Khamsih, bidding him cancel his projected journey

and proceed immediately to Zanjan and there give his assistance to the forces

that had been mustered by the government. "You have been commissioned by your

sovereign," the Amir-Nizam wrote him, "to subjugate the band of mischief-makers

in and around Zanjan. It is your privilege to crush their hopes and exterminate

their forces. So signal a service, at so critical a moment, will win for you the

Shah's highest favour, no less than the applause and esteem of his people."

This encouraging farman stirred the imagination

of the ambitious Sadru'd-Dawlih. He marched instantly on Zanjan at the head of

his two regiments, organised the forces which the governor placed at his disposal,

and gave orders for a combined attack upon the fort and its defenders.(2)

The

This encouraging farman stirred the imagination

of the ambitious Sadru'd-Dawlih. He marched instantly on Zanjan at the head of

his two regiments, organised the forces which the governor placed at his disposal,

and gave orders for a combined attack upon the fort and its defenders.(2)

The

548

contest raged in the environs

of the fort three days and three nights, in the course of which the besieged,

under the direction of Hujjat, resisted with splendid daring the fierce onslaught

of their assailants. Neither their overwhelming numbers nor the superiority of

their equipment and training could enable them to reduce the intrepid companions

to an unconditional surrender.(1)

Undeterred by the fire of the cannon with which they were deluged, and forgetful

of both sleep and hunger, they rushed in a headlong charge out of the fort, utterly

unmindful of the perils incurred by such a sally. To the imprecations with which

an opposing host greeted their appearance from their retreat, they shouted their

answer of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!" and, carried away by the spell which that invocation

threw upon them, hurled themselves upon the enemy and scattered his forces. The

frequency and success of these sallies demoralised their assailants and convinced

them of the futility of their efforts. They were soon compelled to acknowledge

their powerlessness to win a decisive victory. Sadru'd-Dawlih himself had to confess

that after the lapse of nine months of sustained fighting, all the men who had

originally belonged to his two regiments, no more than thirty crippled soldiers

were left to support him. Filled with humiliation, he was forced, eventually,

to admit his powerlessness to daunt the spirit of his opponents. He was degraded

from his rank and gravely reprimanded by his sovereign. The hopes he had fondly

cherished were, as the result of that defeat, irretrievably shattered.

549

So abject a defeat struck dismay into the

hearts of the people of Zanjan. Few were willing, after that disaster, to risk

their lives in hopeless encounters. Only those who were compelled to fight ventured

to renew their attacks upon the besieged. The brunt of the struggle was mainly

borne by the regiments which were being successively despatched from Tihran for

that purpose. While the inhabitants of the town, and particularly the merchant

class among them, profited greatly by the sudden influx of such a large number

of forces, the companions of Hujjat suffered want and privation within the walls

of the fort. Their supplies dwindled rapidly; their only hope of receiving any

food from outside lay in the efforts, often unsuccessful, of a few women who could

manage, under various pretexts, to approach the fort and sell them at an exorbitant

price the provisions they so sadly needed.

So abject a defeat struck dismay into the

hearts of the people of Zanjan. Few were willing, after that disaster, to risk

their lives in hopeless encounters. Only those who were compelled to fight ventured

to renew their attacks upon the besieged. The brunt of the struggle was mainly

borne by the regiments which were being successively despatched from Tihran for

that purpose. While the inhabitants of the town, and particularly the merchant

class among them, profited greatly by the sudden influx of such a large number

of forces, the companions of Hujjat suffered want and privation within the walls

of the fort. Their supplies dwindled rapidly; their only hope of receiving any

food from outside lay in the efforts, often unsuccessful, of a few women who could

manage, under various pretexts, to approach the fort and sell them at an exorbitant

price the provisions they so sadly needed.

Though oppressed with hunger and harassed

by fierce and sudden onsets, they maintained with unflinching determination the

defence of the fort. Sustained by a hope that no amount of adversity could dim,

they succeeded in erecting no less than twenty-eight barricades, each of which

was entrusted to the care of a group of nineteen of their fellow-disciples. At

each barricade, nineteen additional companions were stationed as sentinels, whose

function it was to watch and report the movements of the enemy.

Though oppressed with hunger and harassed

by fierce and sudden onsets, they maintained with unflinching determination the

defence of the fort. Sustained by a hope that no amount of adversity could dim,

they succeeded in erecting no less than twenty-eight barricades, each of which

was entrusted to the care of a group of nineteen of their fellow-disciples. At

each barricade, nineteen additional companions were stationed as sentinels, whose

function it was to watch and report the movements of the enemy.

They were frequently surprised by the voice

of the crier whom the enemy sent to the neighbourhood of the fort to induce its

occupants to desert Hujjat and his Cause. "The governor of the province," he would

proclaim, "and the commander-in-chief too, are willing to forgive and extend a

safe passage to whoever among you will decide to leave the fort and renounce his

faith. Such a man will be amply rewarded by his sovereign, who, in addition to

lavishing gifts upon him, will invest him with the dignity of noble rank. Both

the Shah and his representatives have pledged their honour not to depart from

the promise they have given." To this call the besieged would, with one voice,

return contemptuous and decisive replies.

They were frequently surprised by the voice

of the crier whom the enemy sent to the neighbourhood of the fort to induce its

occupants to desert Hujjat and his Cause. "The governor of the province," he would

proclaim, "and the commander-in-chief too, are willing to forgive and extend a

safe passage to whoever among you will decide to leave the fort and renounce his

faith. Such a man will be amply rewarded by his sovereign, who, in addition to

lavishing gifts upon him, will invest him with the dignity of noble rank. Both

the Shah and his representatives have pledged their honour not to depart from

the promise they have given." To this call the besieged would, with one voice,

return contemptuous and decisive replies.

Further evidence of the spirit of sublime

renunciation animating those valiant companions was afforded by the behaviour

of a village maiden, who, of her own accord, threw

Further evidence of the spirit of sublime

renunciation animating those valiant companions was afforded by the behaviour

of a village maiden, who, of her own accord, threw

550

in her lot with the band

of women and children who had joined the defenders of the fort. Her

name was Zaynab, her home a tiny hamlet in the near neighbourhood of Zanjan. She

was comely and fair of face, was fired with a lofty faith, and endowed with intrepid

courage. The sight of the trials and hardships which her men companions were made

to endure stirred in her an irrepressible yearning to disguise herself in male

attire and share in repulsing the repeated attacks of the enemy. Donning a tunic

and wearing a head-dress like those of her men companions, she cut off her locks,

girt on a sword, and, seizing a musket and a shield, introduced herself into their

ranks. No one suspected her of being a maid when she leaped forward to take her

place behind the barricade. As soon as the enemy charged, she bared her sword

and, raising the cry of "Ya Sahibu'z-Zaman!" flung herself with incredible audacity

upon the forces arrayed against her. Friend and foe marvelled that day at a courage

and resourcefulness the equal of which their eyes had scarcely ever beheld. Her

enemies pronounced her the curse which an angry Providence had hurled upon them.

Overwhelmed with despair and abandoning their barricades, they fled in disgraceful

rout before her.

Hujjat, who was watching the movements of

the enemy from one of the turrets, recognised her and marvelled at the prowess

which that maiden was displaying. She had set out in pursuit of her assailants,

when he ordered his men to bid her return to the fort and give up the attempt.

"No man," he was heard to say, as he saw her plunge into the fire directed upon

her by the enemy, "has shown himself capable of such vitality and courage." When

questioned by him as to the motive of her behaviour, she burst into tears and

said: "My heart ached with pity and sorrow when I beheld the toil and sufferings

of my fellow-disciples. I advanced by an inner urge I could not resist. I was

afraid lest you would deny me the privilege of throwing in my lot with my men

companions." "You are surely the same Zaynab," Hujjat asked her, "who volunteered

to join the occupants of the fort?" "I am," she replied. "I can confidently assure

you that no one has hitherto discovered my sex. You alone have recognised me.

I adjure you by the Bab not to withhold

Hujjat, who was watching the movements of

the enemy from one of the turrets, recognised her and marvelled at the prowess

which that maiden was displaying. She had set out in pursuit of her assailants,

when he ordered his men to bid her return to the fort and give up the attempt.

"No man," he was heard to say, as he saw her plunge into the fire directed upon

her by the enemy, "has shown himself capable of such vitality and courage." When

questioned by him as to the motive of her behaviour, she burst into tears and

said: "My heart ached with pity and sorrow when I beheld the toil and sufferings

of my fellow-disciples. I advanced by an inner urge I could not resist. I was

afraid lest you would deny me the privilege of throwing in my lot with my men

companions." "You are surely the same Zaynab," Hujjat asked her, "who volunteered

to join the occupants of the fort?" "I am," she replied. "I can confidently assure

you that no one has hitherto discovered my sex. You alone have recognised me.

I adjure you by the Bab not to withhold

551

from me that inestimable

privilege, the crown of martyrdom, the one desire of my life."

Hujjat was profoundly impressed by the tone

and manner of her appeal. He sought to calm the tumult of her soul, assured her

of his prayers in her behalf, and gave her the name Rustam-'Ali as a mark of her

noble courage. "This is the Day of Resurrection," he told her, "the day when `all

secrets shall be searched out.'(1)

Not by their outward appearance, but by the character of their beliefs and the

manner of their lives, does God judge His creatures, be they men or women. Though

a maiden of tender age and immature experience, you have displayed such vitality

and resource as few men could hope to surpass." He granted her request, and warned

her not to exceed the bounds their Faith had imposed upon them. "We are called

upon to defend our lives," he reminded her, "against a treacherous assailant,

and not to wage holy war against him."

Hujjat was profoundly impressed by the tone

and manner of her appeal. He sought to calm the tumult of her soul, assured her

of his prayers in her behalf, and gave her the name Rustam-'Ali as a mark of her

noble courage. "This is the Day of Resurrection," he told her, "the day when `all

secrets shall be searched out.'(1)

Not by their outward appearance, but by the character of their beliefs and the

manner of their lives, does God judge His creatures, be they men or women. Though

a maiden of tender age and immature experience, you have displayed such vitality

and resource as few men could hope to surpass." He granted her request, and warned

her not to exceed the bounds their Faith had imposed upon them. "We are called

upon to defend our lives," he reminded her, "against a treacherous assailant,

and not to wage holy war against him."

For a period of no less than five months,

that maiden continued to withstand with unrivalled heroism the forces of the enemy.

Disdainful of food and sleep, she toiled with fevered earnestness for the Cause

she most loved. She quickened, by the example of her splendid daring, the courage

of the few who wavered, and reminded them of the duty each was expected to fulfil.

The sword she wielded remained, throughout that period, by her side. In the brief

intervals of sleep she was able to obtain, she was seen with her head resting

upon her sword and her shield serving as a covering for her body. Every one of

her companions was assigned to a particular post which he was expected to guard

and defend, while that fearless maid alone was free to move in whatever direction

she pleased. Always in the thick and forefront of the turmoil that raged round

her, Zaynab was ever ready to rush to the rescue of whatever post the assailant

was threatening, and to lend her assistance to any one of those who needed either

her encouragement or support. As the end of her life approached, her enemies discovered

her secret, and continued, despite their knowledge that she was a maid, to dread

her influence and to tremble at her approach. The

For a period of no less than five months,

that maiden continued to withstand with unrivalled heroism the forces of the enemy.

Disdainful of food and sleep, she toiled with fevered earnestness for the Cause

she most loved. She quickened, by the example of her splendid daring, the courage

of the few who wavered, and reminded them of the duty each was expected to fulfil.

The sword she wielded remained, throughout that period, by her side. In the brief

intervals of sleep she was able to obtain, she was seen with her head resting

upon her sword and her shield serving as a covering for her body. Every one of

her companions was assigned to a particular post which he was expected to guard

and defend, while that fearless maid alone was free to move in whatever direction

she pleased. Always in the thick and forefront of the turmoil that raged round

her, Zaynab was ever ready to rush to the rescue of whatever post the assailant

was threatening, and to lend her assistance to any one of those who needed either

her encouragement or support. As the end of her life approached, her enemies discovered

her secret, and continued, despite their knowledge that she was a maid, to dread

her influence and to tremble at her approach. The

552

shrill sound of her voice

was sufficient to strike consternation into their hearts and to fill them with

despair.

One day, seeing that her companions were being

suddenly enveloped by the forces of the enemy, Zaynab ran in distress to Hujjat

and, flinging herself at his feet, implored him, with tearful eyes, to allow her

to rush forth to their aid. "My life, I feel, is nearing its end," she added.

"I may myself fall beneath the sword of the assailant. Forgive, I entreat you,

my trespasses, and intercede for me with my Master, for whose sake I yearn to

lay down my life."

One day, seeing that her companions were being

suddenly enveloped by the forces of the enemy, Zaynab ran in distress to Hujjat

and, flinging herself at his feet, implored him, with tearful eyes, to allow her

to rush forth to their aid. "My life, I feel, is nearing its end," she added.

"I may myself fall beneath the sword of the assailant. Forgive, I entreat you,

my trespasses, and intercede for me with my Master, for whose sake I yearn to

lay down my life."

Hujjat was too much overcome with emotion

to reply. Encouraged by his silence, which she interpreted to mean that he consented