142

CHAPTER VIII

THE BAB'S STAY IN SHIRAZ AFTER

THE PILGRIMAGE

HE visit of the Bab to Medina marked the concluding stage of

His pilgrimage to Hijaz. From thence He returned to Jaddih, and by way of the

sea regained His native land. He landed at Bushihr nine lunar months after He

had embarked on His pilgrimage from that port. In the same khan(1)

which He had previously occupied, He received His friends and relatives, who had

come to greet and welcome Him. While still in Bushihr, He summoned Quddus to His

presence and with the utmost kindness bade him depart for Shiraz. "The days of

your companionship with Me," He told him, "are drawing to a close. The hour of

separation has struck, a separation which no reunion will follow except in the

Kingdom of God, in the presence of the King of Glory. In this world of dust, no

more than nine fleeting months of association with Me have been allotted to you.

On the shores of the Great Beyond, however, in the realm of immortality, joy of

eternal reunion awaits us. The hand of destiny will ere long plunge you into an

ocean of tribulation for His sake. I, too, will follow you; I, too, will be immersed

beneath its depths. Rejoice with exceeding gladness, for you have been chosen

as the standard-bearer of the host of affliction, and are standing in the vanguard

of the noble army that will suffer martyrdom in His name. In the streets of Shiraz,

indignities will be heaped upon you, and the severest injuries will afflict your

body. You will survive the ignominious behaviour of your foes, and will attain

the presence of Him who is the one object of our adoration and love. In His presence

you will forget all the harm and disgrace that shall have befallen you. The hosts

of the Unseen will hasten forth to assist you, and will

HE visit of the Bab to Medina marked the concluding stage of

His pilgrimage to Hijaz. From thence He returned to Jaddih, and by way of the

sea regained His native land. He landed at Bushihr nine lunar months after He

had embarked on His pilgrimage from that port. In the same khan(1)

which He had previously occupied, He received His friends and relatives, who had

come to greet and welcome Him. While still in Bushihr, He summoned Quddus to His

presence and with the utmost kindness bade him depart for Shiraz. "The days of

your companionship with Me," He told him, "are drawing to a close. The hour of

separation has struck, a separation which no reunion will follow except in the

Kingdom of God, in the presence of the King of Glory. In this world of dust, no

more than nine fleeting months of association with Me have been allotted to you.

On the shores of the Great Beyond, however, in the realm of immortality, joy of

eternal reunion awaits us. The hand of destiny will ere long plunge you into an

ocean of tribulation for His sake. I, too, will follow you; I, too, will be immersed

beneath its depths. Rejoice with exceeding gladness, for you have been chosen

as the standard-bearer of the host of affliction, and are standing in the vanguard

of the noble army that will suffer martyrdom in His name. In the streets of Shiraz,

indignities will be heaped upon you, and the severest injuries will afflict your

body. You will survive the ignominious behaviour of your foes, and will attain

the presence of Him who is the one object of our adoration and love. In His presence

you will forget all the harm and disgrace that shall have befallen you. The hosts

of the Unseen will hasten forth to assist you, and will

143

proclaim to all the world

your heroism and glory. Yours will be the ineffable joy of quaffing the cup of

martyrdom for His sake. I, too, shall tread the path of sacrifice, and will join

you in the realm of eternity." The Bab then delivered into his hands a letter

He had written to Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, His maternal uncle, in which He had informed

him of His safe return to Bushihr. He also entrusted him with a copy of the Khasa'il-i-Sab'ih,(1)

a treatise in which He had set forth the essential requirements from those who

had attained to the knowledge of the new Revelation and had recognised its claim.

As He bade Quddus His last farewell, He asked him to convey His greetings to each

of His loved ones in Shiraz.

Quddus, with feelings of unshakable

determination to carry out the expressed wishes of his Master, set out from Bushihr.

Arriving at Shiraz, he was affectionately welcomed by Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, who

received him in his own home and eagerly enquired after the health and doings

of his beloved Kinsman. Finding him receptive to the call of the new Message,

Quddus acquainted him with the nature of the Revelation with which that Youth

had already fired his soul. The Bab's maternal uncle, as a result of the endeavours

exerted by Quddus, was the first, after the Letters of the Living, to embrace

the Cause in Shiraz. As the full significance of the new-born Faith had remained

as yet undivulged, he was unaware of the full extent of its implications and glory.

His conversation with Quddus, however, removed the veil from his eyes. So steadfast

became his faith, and so profound grew his love for the Bab, that he consecrated

his whole life to His service. With unrelaxing vigilance he arose to defend His

Cause and to shield His person. In his sustained endeavours, he scorned fatigue

and was disdainful of death. Though recognised as an outstanding figure among

the business men of that city, he never allowed material considerations to interfere

with his spiritual responsibility of safeguarding the person, and advancing the

Cause, of his beloved Kinsman. He persevered in his task until the hour when,

joining the company of the Seven Martyrs of Tihran, he, in circumstances of exceptional

heroism, laid down his life for Him.

Quddus, with feelings of unshakable

determination to carry out the expressed wishes of his Master, set out from Bushihr.

Arriving at Shiraz, he was affectionately welcomed by Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, who

received him in his own home and eagerly enquired after the health and doings

of his beloved Kinsman. Finding him receptive to the call of the new Message,

Quddus acquainted him with the nature of the Revelation with which that Youth

had already fired his soul. The Bab's maternal uncle, as a result of the endeavours

exerted by Quddus, was the first, after the Letters of the Living, to embrace

the Cause in Shiraz. As the full significance of the new-born Faith had remained

as yet undivulged, he was unaware of the full extent of its implications and glory.

His conversation with Quddus, however, removed the veil from his eyes. So steadfast

became his faith, and so profound grew his love for the Bab, that he consecrated

his whole life to His service. With unrelaxing vigilance he arose to defend His

Cause and to shield His person. In his sustained endeavours, he scorned fatigue

and was disdainful of death. Though recognised as an outstanding figure among

the business men of that city, he never allowed material considerations to interfere

with his spiritual responsibility of safeguarding the person, and advancing the

Cause, of his beloved Kinsman. He persevered in his task until the hour when,

joining the company of the Seven Martyrs of Tihran, he, in circumstances of exceptional

heroism, laid down his life for Him.

144

The next person whom Quddus met in Shiraz

was Ismu'llahu'l-Asdaq, Mulla Sadiq-i-Khurasani, to whom he entrusted the copy

of the Khasa'il-i-Sab'ih, and stressed the necessity of putting into effect immediately

all its provisions. Among its precepts was the emphatic injunction of the Bab

to every loyal believer to add the following words to the traditional formula

of the adhan:(1) "I bear witness that

He whose name is Ali-Qabl-i-Muhammad(2) is the servant of the Baqiyyatu'-

The next person whom Quddus met in Shiraz

was Ismu'llahu'l-Asdaq, Mulla Sadiq-i-Khurasani, to whom he entrusted the copy

of the Khasa'il-i-Sab'ih, and stressed the necessity of putting into effect immediately

all its provisions. Among its precepts was the emphatic injunction of the Bab

to every loyal believer to add the following words to the traditional formula

of the adhan:(1) "I bear witness that

He whose name is Ali-Qabl-i-Muhammad(2) is the servant of the Baqiyyatu'-

llah."(3)

Mulla Sadiq, who in those days had been extolling from the pulpit-top to large

audiences the virtues of the imams of the Faith, was so enraptured by the theme

and language of that treatise that he unhesitatingly resolved to carry out all

the observances it ordained. Driven by the impelling force inherent in that Tablet,

he, one day as he was leading his congregation in prayer in the Masjid-i-Naw,

suddenly proclaimed, as he was sounding the adhan, the additional words prescribed

by the Bab. The multitude that

llah."(3)

Mulla Sadiq, who in those days had been extolling from the pulpit-top to large

audiences the virtues of the imams of the Faith, was so enraptured by the theme

and language of that treatise that he unhesitatingly resolved to carry out all

the observances it ordained. Driven by the impelling force inherent in that Tablet,

he, one day as he was leading his congregation in prayer in the Masjid-i-Naw,

suddenly proclaimed, as he was sounding the adhan, the additional words prescribed

by the Bab. The multitude that

145

heard him was astounded by

his cry. Dismay and consternation seized the entire congregation. The distinguished

divines, who occupied the front seats and who were greatly revered for their pious

orthodoxy, raised a clamour, loudly protesting: "Woe betide us, the guardians

and protectors of the Faith of God! Behold, this man has hoisted the standard

of heresy. Down with this infamous traitor! He has spoken blasphemy. Arrest him,

for he is a disgrace to our Faith." "Who," they angrily exclaimed, "dared authorised

such grave departure from the established precepts of Islam? Who has presumed

to arrogate to himself this supreme prerogative?"

The populace re-echoed the protestations of

these divines, and arose to reinforce their clamour. The whole city had been aroused,

and public order was, as a result, seriously threatened. The governor of the province

of Fars, Husayn Khan-i-Iravani, surnamed Ajudan-Bashi, and generally designated

in those days as Sahib-Ikhtiyar,(1)

found it necessary to intervene and to enquire into the cause of this sudden commotion.

He was informed that a disciple of a young man named Siyyid-i-Bab, who had just

returned from His pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina and was now living in Bushihr,

had arrived in Shiraz and was propagating the teachings of his Master. "This disciple,"

Husayn Khan was further informed, "claims that his teacher is the author of a

new revelation and is the revealer of a book which he asserts is divinely inspired.

Mulla Sadiq-i-Khurasani has embraced that faith, and is fearlessly summoning the

multitude to the acceptance of that message. He declares its recognition to be

the first obligation of every loyal and pious follower of shi'ah Islam."

The populace re-echoed the protestations of

these divines, and arose to reinforce their clamour. The whole city had been aroused,

and public order was, as a result, seriously threatened. The governor of the province

of Fars, Husayn Khan-i-Iravani, surnamed Ajudan-Bashi, and generally designated

in those days as Sahib-Ikhtiyar,(1)

found it necessary to intervene and to enquire into the cause of this sudden commotion.

He was informed that a disciple of a young man named Siyyid-i-Bab, who had just

returned from His pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina and was now living in Bushihr,

had arrived in Shiraz and was propagating the teachings of his Master. "This disciple,"

Husayn Khan was further informed, "claims that his teacher is the author of a

new revelation and is the revealer of a book which he asserts is divinely inspired.

Mulla Sadiq-i-Khurasani has embraced that faith, and is fearlessly summoning the

multitude to the acceptance of that message. He declares its recognition to be

the first obligation of every loyal and pious follower of shi'ah Islam."

Husayn Khan ordered the arrest

of both Quddus and Mulla Sadiq. The police authorities, to whom they were delivered,

were instructed to bring them handcuffed into the presence of the governor. The

police also delivered into the hands of Husayn Khan the copy of the Qayyumu'l-Asma',

which they had seized from Mulla Sadiq while he was reading aloud its passages

to an excited congregation. Quddus, owing to his youthful appearance and unconventional

dress, was at first ignored by Husayn Khan, who preferred to direct

Husayn Khan ordered the arrest

of both Quddus and Mulla Sadiq. The police authorities, to whom they were delivered,

were instructed to bring them handcuffed into the presence of the governor. The

police also delivered into the hands of Husayn Khan the copy of the Qayyumu'l-Asma',

which they had seized from Mulla Sadiq while he was reading aloud its passages

to an excited congregation. Quddus, owing to his youthful appearance and unconventional

dress, was at first ignored by Husayn Khan, who preferred to direct

146

his remarks to his more dignified

and elderly companion. "Tell me," angrily asked the governor, as he turned to

Mulla Sadiq, "if you are aware of the opening passage of the Qayyumu'l-Asma' wherein

the Siyyid-i-Bab addresses the rulers and kings of the earth in these terms: `Divest

yourselves of the robe of sovereignty, for He who is the King in truth, hath been

made manifest! The Kingdom is God's, the Most Exalted. Thus hath the Pen of the

Most High decreed!' If this be true, it must necessarily apply to my sovereign,

Muhammad Shah, of the Qajar dynasty,(1)

whom I represent as the chief magistrate of this province. Must Muhammad Shah,

according to this behest, lay down his crown and abandon his sovereignty? Must

I, too, abdicate my power and relinquish my position?" Mulla Sadiq unhesitatingly

replied: "When once the truth of the Revelation announced by the Author of these

words shall have been definitely established, the truth of whatsoever has fallen

from His lips will likewise be vindicated. If these words be the Word of God,

the abdication of Muhammad Shah and his like can matter but little. It can in

no wise turn aside the Divine purpose, nor alter the sovereignty of the almighty

and eternal King."(2)

That cruel and impious ruler was sorely displeased

with such an answer. He reviled and cursed him, ordered his attendants to strip

him of his garments and to scourge him with a thousand lashes. He then commanded

that the beards of both Quddus and Mulla Sadiq should be burned, their noses be

pierced, that through this incision a cord should be passed, and with this halter

they should be led through the streets of the city.(3)

"It will be an object lesson to the people of Shiraz," Husayn Khan declared, "who

will know what the penalty of heresy will be." Mulla Sadiq, calm and self-possessed

and with eyes upraised to heaven, was heard reciting this prayer: "O Lord, our

God! We have indeed heard the voice of One that called. He called us to the

That cruel and impious ruler was sorely displeased

with such an answer. He reviled and cursed him, ordered his attendants to strip

him of his garments and to scourge him with a thousand lashes. He then commanded

that the beards of both Quddus and Mulla Sadiq should be burned, their noses be

pierced, that through this incision a cord should be passed, and with this halter

they should be led through the streets of the city.(3)

"It will be an object lesson to the people of Shiraz," Husayn Khan declared, "who

will know what the penalty of heresy will be." Mulla Sadiq, calm and self-possessed

and with eyes upraised to heaven, was heard reciting this prayer: "O Lord, our

God! We have indeed heard the voice of One that called. He called us to the

147

Faith--`Believe ye on the

Lord your God!'--and we have believed. O God, our God! Forgive us, then, our sins,

and hide away from us our evil deeds, and cause us to die with the righteous."(1)

With magnificent fortitude both resigned themselves to their fate. Those who had

been instructed to inflict this savage punishment performed their task with alacrity

and vigour. None intervened in behalf of these sufferers, none was inclined to

plead their cause. Soon after this, they were both expelled from Shiraz. Before

their expulsion, they were warned that if they ever attempted to return to this

city, they would both be crucified. By their sufferings they earned the immortal

distinction of having been the first to be persecuted on Persian soil for the

sake of their Faith. Mulla Aliy-i-Bastami, though the first to fall a victim to

the relentless hate of the enemy, underwent his persecution in Iraq, which lay

beyond the confines of Persia. Nor did his sufferings, intense as they were, compare

with the hideousness and the barbaric cruelty which characterised the torture

inflicted upon Quddus and Mulla Sadiq.

An eye-witness of this revolting

episode, an unbeliever residing in Shiraz, related to me the following: "I was

present when Mulla Sadiq was being scourged. I watched his persecutors each in

turn apply the lash to his bleeding shoulders, and continue the strokes until

he became exhausted. No one believed that Mulla Sadiq, so advanced in age and

so frail in body, could possibly survive fifty such savage strokes. We marvelled

at his fortitude when we found that, although the number of the strokes of the

scourge he had received had already exceeded nine hundred, his face still retained

its original serenity and calm. A smile was upon his face, as he held his hand

before his mouth. He seemed utterly indifferent to the blows that were being showered

upon him. When he was being expelled from the city, I succeeded in approaching

him, and asked him why he held his hand before his mouth. I expressed surprise

at the smile upon his countenance. He emphatically replied: `The first seven strokes

were severely painful; to the rest I seemed to have grown indifferent. I was wondering

whether the strokes that followed were being actually applied to my own body.

A feeling

An eye-witness of this revolting

episode, an unbeliever residing in Shiraz, related to me the following: "I was

present when Mulla Sadiq was being scourged. I watched his persecutors each in

turn apply the lash to his bleeding shoulders, and continue the strokes until

he became exhausted. No one believed that Mulla Sadiq, so advanced in age and

so frail in body, could possibly survive fifty such savage strokes. We marvelled

at his fortitude when we found that, although the number of the strokes of the

scourge he had received had already exceeded nine hundred, his face still retained

its original serenity and calm. A smile was upon his face, as he held his hand

before his mouth. He seemed utterly indifferent to the blows that were being showered

upon him. When he was being expelled from the city, I succeeded in approaching

him, and asked him why he held his hand before his mouth. I expressed surprise

at the smile upon his countenance. He emphatically replied: `The first seven strokes

were severely painful; to the rest I seemed to have grown indifferent. I was wondering

whether the strokes that followed were being actually applied to my own body.

A feeling

148

of joyous exultation had

invaded my soul. I was trying to repress my feelings and to restrain my laughter.

I can now realise how the almighty Deliverer is able, in the twinkling of an eye,

to turn pain into ease, and sorrow into gladness. Immensely exalted is His power

above and beyond the idle fancy of His mortal creatures.'" Mulla Sadiq, whom I

met years after, confirmed every detail of this moving episode.

Husayn Khan's anger was not appeased by this

atrocious and most undeserved chastisement. His wanton and capricious cruelty

found further vent in the assault which he now directed against the person of

the Bab.(1) He despatched to

Bushihr a mounted escort of his own trusted guard, with emphatic instructions

to arrest the Bab and to bring Him in chains to Shiraz. The leader of that escort,

a member of the Nusayri community, better known as the sect of Aliyu'llahi, related

the following: "Having completed the third stage of our journey to Bushihr, we

encountered, in the midst of the wilderness a youth who wore a green sash and

a small turban after the manner of the siyyids who are in the trading profession.

He was on horseback, and was followed by an Ethiopian servant who was in charge

of his belongings. As we approached him, he saluted us and enquired as to our

destination. I thought it best to conceal from him the truth, and replied that

in this vicinity we had been commanded by the governor of Fars to conduct a certain

enquiry. He smilingly observed: `The governor has sent you to arrest Me. Here

am I; do with Me as you please. By

Husayn Khan's anger was not appeased by this

atrocious and most undeserved chastisement. His wanton and capricious cruelty

found further vent in the assault which he now directed against the person of

the Bab.(1) He despatched to

Bushihr a mounted escort of his own trusted guard, with emphatic instructions

to arrest the Bab and to bring Him in chains to Shiraz. The leader of that escort,

a member of the Nusayri community, better known as the sect of Aliyu'llahi, related

the following: "Having completed the third stage of our journey to Bushihr, we

encountered, in the midst of the wilderness a youth who wore a green sash and

a small turban after the manner of the siyyids who are in the trading profession.

He was on horseback, and was followed by an Ethiopian servant who was in charge

of his belongings. As we approached him, he saluted us and enquired as to our

destination. I thought it best to conceal from him the truth, and replied that

in this vicinity we had been commanded by the governor of Fars to conduct a certain

enquiry. He smilingly observed: `The governor has sent you to arrest Me. Here

am I; do with Me as you please. By

149

coming out to meet you, I

have curtailed the length of your march, and have made it easier for you to find

Me.' I was startled by his remarks and marvelled at his candour and straightforwardness.

I could not explain, however, his readiness to subject himself, of his own accord,

to the severe discipline of government officials, and to risk thereby his own

life and safety. I tried to ignore him, and was preparing to leave, when he approached

me and said: `I swear by the righteousness of Him who created man, distinguished

him from among the rest of His creatures, and caused his heart to be made the

seat of His sovereignty and knowledge, that all My life I have uttered no word

but the truth, and had no other desire except the welfare and advancement of My

fellow-men. I have disdained My own ease and have avoided being the cause of pain

or sorrow to anyone. I know that you are seeking Me. I prefer to deliver Myself

into your hands, rather than subject you and your companions to unnecessary annoyance

for My sake.' These words moved me profoundly. I instinctively dismounted from

my horse, and, kissing his stirrups, addressed him in these words: `O light of

the eyes of the Prophet of God! I adjure you, by Him who has created you and endowed

you with such loftiness and power, to grant my request and to answer my prayer.

I beseech you to escape from this place and to flee from before the face of Husayn

Khan, the ruthless and despicable governor of this province. I dread his machinations

against you; I rebel at the idea of being made the instrument of his malignant

designs against so innocent and noble a descendant of the Prophet of God. My companions

are all honourable men. Their word is their bond. They will pledge themselves

not to betray your flight. I pray you, betake yourself to the city of Mashhad

in Khurasan, and avoid falling a victim to the brutality of this remorseless wolf.'

To my earnest entreaty he gave this answer: `May the Lord your God requite you

for your magnanimity and noble intention. No one knows the mystery of My Cause;

no one can fathom its secrets. Never will I turn My face away from the decree

of God. He alone is My sure Stronghold, My Stay and My Refuge. Until My last hour

is at hand, none dare assail Me, none can frustrate the plan of the Almighty.

And when

150

My hour is come, how great

will be My joy to quaff the cup of martyrdom in His name! Here am I; deliver Me

into the hands of your master. Be not afraid, for no one will blame you.' I bowed

my consent and carried out his desire."

The Bab

straightway resumed His journey to Shiraz. Free and unfettered, He went before

His escort, which followed Him in an attitude of respectful devotion. By the magic

of His words, He had disarmed the hostility of His guards and transmuted their

proud arrogance into humility and love. Reaching the city, they proceeded directly

to the seat of the government. Whosoever observed the cavalcade marching through

the streets could not help but marvel at this most unusual spectacle. Immediately

Husayn Khan was informed of the arrival of the Bab, he summoned Him to his presence.

He received Him with the utmost insolence and bade Him occupy a seat facing him

in the centre of the room. He publicly rebuked Him, and in abusive language denounced

His conduct. "Do you realise," he angrily protested, "what a great mischief you

have kindled? Are you aware what a disgrace you have become to the holy Faith

of Islam and to the august person of our sovereign? Are you not the man who claims

to be the author of a new revelation which annuls the sacred precepts of the Qur'an?"

The Bab calmly replied: "`If any bad man come unto you with news, clear up the

matter at once, lest through ignorance ye harm others, and be speedily constrained

to repent of what ye have done.'"(1)

These words inflamed the wrath of Husayn Khan. "What!" he exclaimed. "Dare you

ascribe to us evil, ignorance, and folly?" Turning to his attendant, he bade him

strike the Bab in the face. So violent was the blow, that the Bab's turban fell

to the ground. Shaykh Abu-Turab, the Imam-Jum'ih of Shiraz, who was present at

that meeting and who strongly disapproved of the conduct of Husayn Khan, ordered

that the Bab's turban be replaced upon His head, and invited Him to be seated

by his side. Turning to the governor, the Imam-Jum'ih explained to him the circumstances

connected with the revelation of the verse of the Qur'an which the Bab had quoted,

and sought by this means to calm his fury. "This verse which this youth has

The Bab

straightway resumed His journey to Shiraz. Free and unfettered, He went before

His escort, which followed Him in an attitude of respectful devotion. By the magic

of His words, He had disarmed the hostility of His guards and transmuted their

proud arrogance into humility and love. Reaching the city, they proceeded directly

to the seat of the government. Whosoever observed the cavalcade marching through

the streets could not help but marvel at this most unusual spectacle. Immediately

Husayn Khan was informed of the arrival of the Bab, he summoned Him to his presence.

He received Him with the utmost insolence and bade Him occupy a seat facing him

in the centre of the room. He publicly rebuked Him, and in abusive language denounced

His conduct. "Do you realise," he angrily protested, "what a great mischief you

have kindled? Are you aware what a disgrace you have become to the holy Faith

of Islam and to the august person of our sovereign? Are you not the man who claims

to be the author of a new revelation which annuls the sacred precepts of the Qur'an?"

The Bab calmly replied: "`If any bad man come unto you with news, clear up the

matter at once, lest through ignorance ye harm others, and be speedily constrained

to repent of what ye have done.'"(1)

These words inflamed the wrath of Husayn Khan. "What!" he exclaimed. "Dare you

ascribe to us evil, ignorance, and folly?" Turning to his attendant, he bade him

strike the Bab in the face. So violent was the blow, that the Bab's turban fell

to the ground. Shaykh Abu-Turab, the Imam-Jum'ih of Shiraz, who was present at

that meeting and who strongly disapproved of the conduct of Husayn Khan, ordered

that the Bab's turban be replaced upon His head, and invited Him to be seated

by his side. Turning to the governor, the Imam-Jum'ih explained to him the circumstances

connected with the revelation of the verse of the Qur'an which the Bab had quoted,

and sought by this means to calm his fury. "This verse which this youth has

151

quoted," he told him, "has

made a profound impression upon me. The wise course, I feel, is to enquire into

this matter with great care, and to judge him according to the precepts of the

holy Book." Husayn Khan readily consented; whereupon Shaykh Abu-Turab questioned

the Bab regarding the nature and character of His Revelation. The Bab denied the

claim of being either the representative of the promised Qa'im or the intermediary

between Him and the faithful. "We are completely satisfied," replied the Imam-Jum'ih;

"we shall request you to present yourself on Friday in the Masjid-i-Vakil, and

to proclaim publicly your denial." As Shaykh Abu-Turab arose to depart in the

hope of terminating the proceedings, Husayn Khan intervened and said: "We shall

require a person of recognised standing to give bail and surety for him, and to

pledge his word in writing that if ever in future this youth should attempt by

word or deed to prejudice the interests either of the Faith of Islam or of the

government of this land, he would straightway deliver him into our hands, and

regard himself under all circumstances responsible for his behaviour." Haji Mirza

Siyyid Ali, the Bab's maternal uncle, who was present at that meeting, consented

to act as the sponsor of his Nephew. In his own handwriting he wrote the pledge,

affixed to it his seal, confirmed it by the signature of a number of witnesses,

and delivered it to the governor; whereupon Husayn Khan ordered that the Bab be

entrusted to the care of His uncle, with the condition that at whatever time the

governor should deem it advisable, Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali would at once deliver

the Bab into his hands.

Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, his heart filled with

gratitude to God, conducted the Bab to His home and committed Him to the loving

care of His revered mother. He rejoiced at this family reunion and was greatly

relieved by the deliverance of his dear and precious Kinsman from the grasp of

that malignant tyrant. In the quiet of His own home, the Bab led for a time a

life of undisturbed retirement. No one except His wife, His mother, and His uncles

had any intercourse with Him. Meanwhile the mischief-makers were busily pressing

Shaykh Abu-Turab to summon the Bab to the Masjid-i-Vakil and to call upon Him

to fulfil His pledge.

Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, his heart filled with

gratitude to God, conducted the Bab to His home and committed Him to the loving

care of His revered mother. He rejoiced at this family reunion and was greatly

relieved by the deliverance of his dear and precious Kinsman from the grasp of

that malignant tyrant. In the quiet of His own home, the Bab led for a time a

life of undisturbed retirement. No one except His wife, His mother, and His uncles

had any intercourse with Him. Meanwhile the mischief-makers were busily pressing

Shaykh Abu-Turab to summon the Bab to the Masjid-i-Vakil and to call upon Him

to fulfil His pledge.

152

153

Shaykh Abu-Turab was known

to be a man of kindly disposition, and of a temperament and nature which bore

a striking resemblance to the character of the late Mirza Abu'l-Qasim, the Imam-Jum'ih

of Tihran. He was extremely reluctant to treat with contumely persons of recognised

standing, particularly if these were residents of Shiraz. Instinctively he felt

this to be his duty, observed it conscientiously, and was as a result universally

esteemed by the people of that city. He therefore sought, through evasive answers

and repeated postponements, to appease the indignation of the multitude. He found,

however, that the stirrers-up of mischief and sedition were bending every effort

further to inflame the feelings of general resentment which had seized the masses.

He at length felt compelled to address a confidential message to Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali, requesting him to bring the Bab with him on Friday to the Masjid-i-Vakil,

that He might fulfil the pledge He had given. "My hope," he added, "is that by

the aid of God the statements of your nephew may ease the tenseness of the situation

and may lead to your tranquillity as well as to our own."

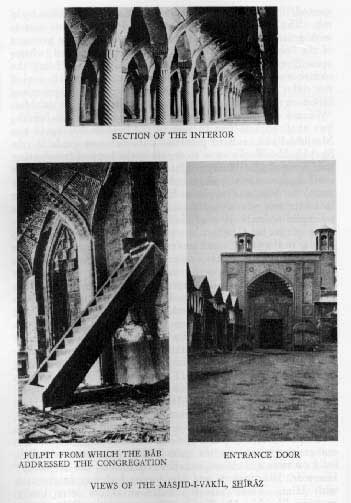

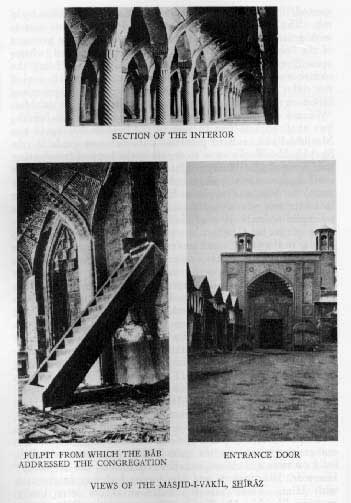

The Bab, accompanied by Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali, arrived at the Masjid at a time when the Imam-Jum'ih had just ascended the

pulpit and was preparing to deliver his sermon. As soon as his eyes fell upon

the Bab, he publicly welcomed Him, requested Him to ascend the pulpit, and called

upon Him to address the congregation. The Bab, responding to his invitation, advanced

towards him and, standing on the first step of the staircase, prepared to address

the people. "Come up higher," interjected the Imam-Jum'ih. Complying with his

wish, the Bab ascended two more steps. As He was standing, His head hid the breast

of Shaykh Abu-Turab, who was occupying the pulpit-top. He began by prefacing His

public declaration with an introductory discourse. No sooner had He uttered the

opening words of "Praise be to God, who hath in truth created the heavens and

the earth," than a certain siyyid known as Siyyidi-Shish-Pari, whose function

was to carry the mace before the Imam-Jum'ih, insolently shouted: "Enough of this

idle chatter! Declare, now and immediately, the thing you intend to say." The

Imam-Jum'ih greatly resented the rudeness of the siyyid's

The Bab, accompanied by Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali, arrived at the Masjid at a time when the Imam-Jum'ih had just ascended the

pulpit and was preparing to deliver his sermon. As soon as his eyes fell upon

the Bab, he publicly welcomed Him, requested Him to ascend the pulpit, and called

upon Him to address the congregation. The Bab, responding to his invitation, advanced

towards him and, standing on the first step of the staircase, prepared to address

the people. "Come up higher," interjected the Imam-Jum'ih. Complying with his

wish, the Bab ascended two more steps. As He was standing, His head hid the breast

of Shaykh Abu-Turab, who was occupying the pulpit-top. He began by prefacing His

public declaration with an introductory discourse. No sooner had He uttered the

opening words of "Praise be to God, who hath in truth created the heavens and

the earth," than a certain siyyid known as Siyyidi-Shish-Pari, whose function

was to carry the mace before the Imam-Jum'ih, insolently shouted: "Enough of this

idle chatter! Declare, now and immediately, the thing you intend to say." The

Imam-Jum'ih greatly resented the rudeness of the siyyid's

154

remark. "Hold your peace,"

he rebuked him, "and be ashamed of your impertinence." He then, turning to the

Bab, asked Him to be brief, as this, he said, would allay the excitement of the

people. The Bab, as He faced the congregation, declared: "The condemnation of

God be upon him who regards me either as a representative of the Imam or the gate

thereof. The condemnation of God be also upon whosoever imputes to me the charge

of having denied the unity of God, of having repudiated the prophethood of Muhammad,

the Seal of the Prophets, of having rejected the truth of any of the messengers

of old, or of having refused to recognise the guardianship of Ali, the Commander

of the Faithful, or of any of the imams who have succeeded him." He then ascended

to the top of the staircase, embraced the Imam-Jum'ih, and, descending to the

floor of the Masjid, joined the congregation for the observance of the Friday

prayer. The Imam-Jum'ih intervened and requested Him to retire. "Your family,"

he said, "is anxiously awaiting your return. All are apprehensive lest any harm

befall you. Repair to your house and there offer your prayer; of greater merit

shall this deed be in the sight of God." Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali also was, at the

request of the Imam-Jum'ih, asked to accompany his nephew to his home. This precautionary

measure which Shaykh Abu-Turab thought it wise to observe was actuated by the

fear lest, after the dispersion of the congregation, a few of the evil-minded

among the crowd might still attempt to injure the person of the Bab or endanger

His life. But for the sagacity, the sympathy, and the careful attention which

the Imam-Jum'ih so strikingly displayed on a number of such occasions, the infuriated

mob would doubtless have been led to gratify its savage desire, and would have

committed the most abominable of excesses. He seemed to have been the instrument

of the invisible Hand appointed to protect both the person and the Mission of

that Youth.(1)

155

The Bab regained His home and for some time

was able to lead, in the privacy of His house, and in close association with His

family and kinsmen, a life of comparative tranquillity. In those days He celebrated

the advent of the first Naw-Ruz since He had declared His Mission. That festival

fell, in that year, on the tenth day of the month of Rabi'u'l-Avval, 1261 A.H.(1)

The Bab regained His home and for some time

was able to lead, in the privacy of His house, and in close association with His

family and kinsmen, a life of comparative tranquillity. In those days He celebrated

the advent of the first Naw-Ruz since He had declared His Mission. That festival

fell, in that year, on the tenth day of the month of Rabi'u'l-Avval, 1261 A.H.(1)

A few among those who were present on that

memorable occasion in the Masjid-i-Vakil, and had listened to the statements of

the Bab, were greatly impressed by the masterly manner in which that Youth had,

by His unaided efforts, succeeded in silencing His formidable opponents. Soon

after this event, they were each led to apprehend the reality of His Mission and

to recognise its glory. Among them was Shaykh Ali Mirza, the nephew of this same

Imam-Jum'ih, a young man who had just attained the age of maturity. The seed implanted

in his heart grew and developed, until in the year 1267 A.H.(2)

he was privileged to meet Baha'u'llah in Iraq. That visit filled him with enthusiasm

and joy. Returning greatly refreshed to his native land, he resumed with redoubled

energy his labours for the Cause. From that year until the present time, he has

persevered in his task, and has achieved distinction by the uprightness of his

character and whole-hearted devotion to his government and country. Recently a

letter addressed by him to Baha'u'llah has reached the Holy Land, in which he

expresses his keen satisfaction at the progress of the Cause in Persia. "I am

mute with wonder," he writes, "when I behold the evidences of God's unconquerable

power manifested among the people of my country. In a land which has for years

so savagely persecuted the Faith, a man who for forty years has been known throughout

Persia as a Babi, has been made the sole arbitrator in a case of dispute which

involves, on the one hand, the Zillu's-Sultan, the tyrannical son of the Shah

and a sworn enemy of the Cause, and, on the other, Mirza Fath-'Ali Khan, the Sahib-i-Divan.

It has been publicly announced that whatsoever be the verdict of this Babi, the

same should be unreservedly accepted by both parties and should be unhesitatingly

enforced."

A few among those who were present on that

memorable occasion in the Masjid-i-Vakil, and had listened to the statements of

the Bab, were greatly impressed by the masterly manner in which that Youth had,

by His unaided efforts, succeeded in silencing His formidable opponents. Soon

after this event, they were each led to apprehend the reality of His Mission and

to recognise its glory. Among them was Shaykh Ali Mirza, the nephew of this same

Imam-Jum'ih, a young man who had just attained the age of maturity. The seed implanted

in his heart grew and developed, until in the year 1267 A.H.(2)

he was privileged to meet Baha'u'llah in Iraq. That visit filled him with enthusiasm

and joy. Returning greatly refreshed to his native land, he resumed with redoubled

energy his labours for the Cause. From that year until the present time, he has

persevered in his task, and has achieved distinction by the uprightness of his

character and whole-hearted devotion to his government and country. Recently a

letter addressed by him to Baha'u'llah has reached the Holy Land, in which he

expresses his keen satisfaction at the progress of the Cause in Persia. "I am

mute with wonder," he writes, "when I behold the evidences of God's unconquerable

power manifested among the people of my country. In a land which has for years

so savagely persecuted the Faith, a man who for forty years has been known throughout

Persia as a Babi, has been made the sole arbitrator in a case of dispute which

involves, on the one hand, the Zillu's-Sultan, the tyrannical son of the Shah

and a sworn enemy of the Cause, and, on the other, Mirza Fath-'Ali Khan, the Sahib-i-Divan.

It has been publicly announced that whatsoever be the verdict of this Babi, the

same should be unreservedly accepted by both parties and should be unhesitatingly

enforced."

156

A certain Muhammad-Karim who was among the

congregation that Friday was likewise attracted by the Bab's remarkable behaviour

on that occasion. What he saw and heard on that day brought about his immediate

conversion. Persecution drove him out of Persia to Iraq, where, in the presence

of Baha'u'llah, he continually deepened his understanding and faith. Later on

he was bidden by Him to return to Shiraz and to endeavour to the best of his ability

to propagate the Cause. There he remained and laboured to the end of his life.

A certain Muhammad-Karim who was among the

congregation that Friday was likewise attracted by the Bab's remarkable behaviour

on that occasion. What he saw and heard on that day brought about his immediate

conversion. Persecution drove him out of Persia to Iraq, where, in the presence

of Baha'u'llah, he continually deepened his understanding and faith. Later on

he was bidden by Him to return to Shiraz and to endeavour to the best of his ability

to propagate the Cause. There he remained and laboured to the end of his life.

Still another was Mirza Aqay-i-Rikab-Saz.

He became so enamoured of the Bab on that day that no persecution, however severe

and prolonged, was able either to shake his convictions or to obscure the radiance

of his love. He, too, attained the presence of Baha'u'llah in Iraq. In answer

to the questions which he asked regarding the interpretation of the Disconnected

Letters of the Qur'an and the meaning of the Verse of Nur, he was favoured with

an expressly written Tablet revealed by the pen of Baha'u'llah. In His path he

eventually suffered martyrdom.

Still another was Mirza Aqay-i-Rikab-Saz.

He became so enamoured of the Bab on that day that no persecution, however severe

and prolonged, was able either to shake his convictions or to obscure the radiance

of his love. He, too, attained the presence of Baha'u'llah in Iraq. In answer

to the questions which he asked regarding the interpretation of the Disconnected

Letters of the Qur'an and the meaning of the Verse of Nur, he was favoured with

an expressly written Tablet revealed by the pen of Baha'u'llah. In His path he

eventually suffered martyrdom.

Among them also was Mirza Rahim-i-Khabbaz,

who distinguished himself by his fearlessness and fiery ardour. He relaxed not

in his efforts until the hour of his death.

Among them also was Mirza Rahim-i-Khabbaz,

who distinguished himself by his fearlessness and fiery ardour. He relaxed not

in his efforts until the hour of his death.

Haji Abu'l-Hasan-i-Bazzaz, who, as a fellow-traveller

of the Bab during His pilgrimage to Hijaz, had but dimly recognised the overpowering

majesty of His Mission, was, on that memorable Friday, profoundly shaken and completely

transformed. He bore the Bab such love that tears of an overpowering devotion

continually flowed from his eyes. All who knew him admired the uprightness of

his conduct and praised his benevolence and candour. He, as well as his two sons,

has proved by his deeds the tenacity of his faith, and has won the esteem of his

fellow-believers.

Haji Abu'l-Hasan-i-Bazzaz, who, as a fellow-traveller

of the Bab during His pilgrimage to Hijaz, had but dimly recognised the overpowering

majesty of His Mission, was, on that memorable Friday, profoundly shaken and completely

transformed. He bore the Bab such love that tears of an overpowering devotion

continually flowed from his eyes. All who knew him admired the uprightness of

his conduct and praised his benevolence and candour. He, as well as his two sons,

has proved by his deeds the tenacity of his faith, and has won the esteem of his

fellow-believers.

And yet another of those who felt the fascination

of the Bab on that day was the late Haji Muhammad-Bisat, a man well-versed in

the metaphysical teachings of Islam and a great admirer of both Shaykh Ahmad and

Siyyid Kazim. He was of a kindly disposition and was gifted with a keen sense

of humour. He had won the friendship of the Imam-Jum'ih,

And yet another of those who felt the fascination

of the Bab on that day was the late Haji Muhammad-Bisat, a man well-versed in

the metaphysical teachings of Islam and a great admirer of both Shaykh Ahmad and

Siyyid Kazim. He was of a kindly disposition and was gifted with a keen sense

of humour. He had won the friendship of the Imam-Jum'ih,

157

was intimately associated

with him, and was a faithful attendant at the Friday congregational prayer.

The Naw-Ruz of that year,

which heralded the advent of a new springtime, was also symbolic of that spiritual

rebirth, the first stirring of which could already be discerned throughout the

length and breadth of the land. A number of the most eminent and learned among

the people of that country emerged from the wintry desolation of heedlessness,

and were quickened by the reviving breath of the new-born Revelation. The seeds

which the Hand of Omnipotence had implanted in their hearts germinated into blossoms

of the purest and loveliest fragrance.(1)

As the breeze of His loving-kindness and tender mercy wafted over these blossoms,

the penetrating power of their perfume spread far and wide over the face of all

that land. It diffused itself even beyond the confines of Persia. It reached Karbila

and reanimated the souls of those who were waiting in expectation for the return

158

of the Bab to their city.

Soon after Naw-Ruz, an epistle reached them by way of Basrih, in which the Bab,

who had intended to return from Hijaz to Persia by way of Karbila, informed them

of the change in His plan and of His consequent inability to fulfil His promise.

He directed them to proceed to Isfahan and remain there until the receipt of further

instructions. "Should it be deemed advisable," He added, "We shall request you

to proceed to Shiraz; if not, tarry in Isfahan until such time as God may make

known to you His will and guidance."

The receipt of this unexpected intelligence

created a considerable stir among those who had been eagerly awaiting the arrival

of the Bab at Karbila. It agitated their minds and tested their loyalty. "What

of His promise to us?" whispered a few of the discontented among them. "Does He

regard the breaking of His pledge as the interposition of the will of God?" The

others, unlike those waverers, became more steadfast in their faith and clung

with added determination to the Cause. Faithful to their Master, they joyously

responded to His invitation, ignoring entirely the criticisms and protestations

of those who had faltered in their faith.

The receipt of this unexpected intelligence

created a considerable stir among those who had been eagerly awaiting the arrival

of the Bab at Karbila. It agitated their minds and tested their loyalty. "What

of His promise to us?" whispered a few of the discontented among them. "Does He

regard the breaking of His pledge as the interposition of the will of God?" The

others, unlike those waverers, became more steadfast in their faith and clung

with added determination to the Cause. Faithful to their Master, they joyously

responded to His invitation, ignoring entirely the criticisms and protestations

of those who had faltered in their faith.

159

They set out for Isfahan,

determined to abide by whatsoever might be the will and desire of their Beloved.

They were joined by a few of their companions, who, though gravely shaken in their

belief, concealed their feelings. Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Nahri, whose daughter

was subsequently joined in wedlock with the Most Great Branch, and Mirza Hadi,

the brother of Mirza Muhammad-'Ali, both residents of Isfahan, were among those

companions whose vision of the glory and sublimity of the Faith the expressed

misgivings of the evil whisperers had failed to obscure. Among them, too, was

a certain Muhammad-i-Hana-Sab, also a resident of Isfahan, who is now serving

in the home of Baha'u'llah. A number of these staunch companions of the Bab participated

in the great struggle of Shaykh Tabarsi and miraculously escaped the tragic fate

of their fallen brethren.

On their way to Isfahan they

met, in the city of Kangavar, Mulla Husayn with his brother and nephew, who were

his companions on his previous visit to Shiraz, and who were proceeding to Karbila.

They were greatly delighted by this unexpected encounter, and requested Mulla

Husayn to prolong his stay in Kangavar, with which request he readily complied.

Mulla Husayn, who, while in that city, led the companions of the Bab in the Friday

congregational prayer, was held in such esteem and reverence by his fellow-disciples

that a number of those present, who later on, in Shiraz, revealed their disloyalty

to the Faith, were moved with envy. Among them were Mulla Javad-i-Baraghani and

Mulla Abdu'l-'Aliy-i-Harati, both of whom feigned submission to the Revelation

of the Bab in the hope of satisfying their ambition for leadership. They both

strove secretly to undermine the enviable position achieved by Mulla Husayn. Through

their hints and insinuations, they persistently endeavoured to challenge his authority

and disgrace his name.

On their way to Isfahan they

met, in the city of Kangavar, Mulla Husayn with his brother and nephew, who were

his companions on his previous visit to Shiraz, and who were proceeding to Karbila.

They were greatly delighted by this unexpected encounter, and requested Mulla

Husayn to prolong his stay in Kangavar, with which request he readily complied.

Mulla Husayn, who, while in that city, led the companions of the Bab in the Friday

congregational prayer, was held in such esteem and reverence by his fellow-disciples

that a number of those present, who later on, in Shiraz, revealed their disloyalty

to the Faith, were moved with envy. Among them were Mulla Javad-i-Baraghani and

Mulla Abdu'l-'Aliy-i-Harati, both of whom feigned submission to the Revelation

of the Bab in the hope of satisfying their ambition for leadership. They both

strove secretly to undermine the enviable position achieved by Mulla Husayn. Through

their hints and insinuations, they persistently endeavoured to challenge his authority

and disgrace his name.

I have heard Mirza Ahmad-i-Katib, better known

in those days as Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, who had been the travelling companion of

Mulla Javad from Qazvin, relate the following: " Mulla Javad often alluded in

his conversation with me to Mulla Husayn. His repeated and disparaging remarks,

couched in artful language, impelled me to cease my association with him. Every

time I determined to sever my

I have heard Mirza Ahmad-i-Katib, better known

in those days as Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, who had been the travelling companion of

Mulla Javad from Qazvin, relate the following: " Mulla Javad often alluded in

his conversation with me to Mulla Husayn. His repeated and disparaging remarks,

couched in artful language, impelled me to cease my association with him. Every

time I determined to sever my

160

intercourse with Mulla Javad,

I was prevented by Mulla Husayn, who, discovering my intention, counselled me

to exercise forbearance towards him. Mulla Husayn's association with the loyal

companions of the Bab greatly added to their zeal and enthusiasm. They were edified

by his example and were lost in admiration for the brilliant qualities of mind

and heart which distinguished so eminent a fellow-disciple."

Mulla Husayn decided to join

the company of his friends and to proceed with them to Isfahan. Travelling alone,

at about a farsakh's(1)

distance in advance of his companions, he, as soon as he paused at nightfall to

offer his prayer, would be overtaken by them and would, in their company, complete

his devotions. He would be the first to resume the journey, and would again be

joined by that devoted band at the hour of dawn, when he once more would break

his march to offer his prayer. Only when pressed by his friends would he consent

to observe the congregational form of worship. On such occasions he would sometimes

follow the lead of one of his companions. Such was the devotion which he had kindled

in those hearts that a number of his fellow-travellers would dismount from their

steeds and, offering them to those who were journeying on foot, would themselves

follow him, utterly indifferent to the strain and fatigues of the march.

Mulla Husayn decided to join

the company of his friends and to proceed with them to Isfahan. Travelling alone,

at about a farsakh's(1)

distance in advance of his companions, he, as soon as he paused at nightfall to

offer his prayer, would be overtaken by them and would, in their company, complete

his devotions. He would be the first to resume the journey, and would again be

joined by that devoted band at the hour of dawn, when he once more would break

his march to offer his prayer. Only when pressed by his friends would he consent

to observe the congregational form of worship. On such occasions he would sometimes

follow the lead of one of his companions. Such was the devotion which he had kindled

in those hearts that a number of his fellow-travellers would dismount from their

steeds and, offering them to those who were journeying on foot, would themselves

follow him, utterly indifferent to the strain and fatigues of the march.

As they approached the outskirts

of Isfahan, Mulla Husayn, fearing that the sudden entry of so large a group of

people might excite the curiosity and suspicion of its inhabitants, advised those

who were travelling with him to disperse and to enter the gates in small and inconspicuous

numbers. A few days after their arrival, there reached them the news that Shiraz

was in a state of violent agitation, that all manner of intercourse with the Bab

had been forbidden, and that their projected visit to that city would be fraught

with the gravest danger. Mulla Husayn, quite undaunted by this sudden intelligence,

decided to proceed to Shiraz. He acquainted only a few of his trusted companions

with his intention. Discarding his robes and turban, and wearing the jubbih (2)

and kulah of the people of Khurasan, he, disguising himself as a horseman of Hizarih

and Quchan and accompanied by his brother and nephew, set out at an unexpected

hour for the

As they approached the outskirts

of Isfahan, Mulla Husayn, fearing that the sudden entry of so large a group of

people might excite the curiosity and suspicion of its inhabitants, advised those

who were travelling with him to disperse and to enter the gates in small and inconspicuous

numbers. A few days after their arrival, there reached them the news that Shiraz

was in a state of violent agitation, that all manner of intercourse with the Bab

had been forbidden, and that their projected visit to that city would be fraught

with the gravest danger. Mulla Husayn, quite undaunted by this sudden intelligence,

decided to proceed to Shiraz. He acquainted only a few of his trusted companions

with his intention. Discarding his robes and turban, and wearing the jubbih (2)

and kulah of the people of Khurasan, he, disguising himself as a horseman of Hizarih

and Quchan and accompanied by his brother and nephew, set out at an unexpected

hour for the

161

city of his Beloved. As he

approached its gate, he instructed his brother to proceed in the dead of night

to the house of the Bab's maternal uncle and to request him to inform the Bab

of his arrival. Mulla Husayn received, the next day, the welcome news that Haji

Mirza Siyyid Ali was expecting him an hour after sunset outside the gate of the

city. Mulla Husayn met him at the appointed hour and was conducted to his home.

Several times at night did the Bab honour that house with His presence, and continue

in close association with Mulla Husayn until the break of day. Soon after this,

He gave permission to His companions who had gathered in Isfahan, to leave gradually

for Shiraz, and there to wait until it should be feasible for Him to meet them.

He cautioned them to exercise the utmost vigilance, instructed them to enter,

a few at a time, the gate of the city, and bade them disperse, immediately upon

their arrival, into such quarters as were reserved for travellers, and accept

whatever employment they could find.

The first group to reach the

city and meet the Bab, a few days after the arrival of Mulla Husayn, consisted

of Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Nahri, Mirza Hadi, his brother; Mulla Abdu'l-Karim-i-Qazvini,

Mulla Javad-i-Baraghani, Mulla Abdu'l-'Aliy-i-Harati, and Mirza Ibrahim-i-Shirazi.

In the course of their association with Him, the last three of the group gradually

betrayed their blindness of heart and demonstrated the baseness of their character.

The manifold evidences of the Bab's increasing favour towards Mulla Husayn aroused

their anger and excited the smouldering fire of their jealousy. In their impotent

rage, they resorted to the abject weapons of fraud and of calumny. Unable at first

to manifest openly their hostility to Mulla Husayn, they sought by every crafty

device to beguile the minds and damp the affections of his devoted admirers. Their

unseemly behaviour alienated the sympathy of the believers and precipitated their

separation from the company of the faithful. Expelled by their very acts from

the bosom of the Faith, they leagued themselves with its avowed enemies and proclaimed

their utter rejection of its claims and principles. So great was the mischief

which they stirred up among the people of that city that they were eventually

expelled by the civil authorities,

The first group to reach the

city and meet the Bab, a few days after the arrival of Mulla Husayn, consisted

of Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Nahri, Mirza Hadi, his brother; Mulla Abdu'l-Karim-i-Qazvini,

Mulla Javad-i-Baraghani, Mulla Abdu'l-'Aliy-i-Harati, and Mirza Ibrahim-i-Shirazi.

In the course of their association with Him, the last three of the group gradually

betrayed their blindness of heart and demonstrated the baseness of their character.

The manifold evidences of the Bab's increasing favour towards Mulla Husayn aroused

their anger and excited the smouldering fire of their jealousy. In their impotent

rage, they resorted to the abject weapons of fraud and of calumny. Unable at first

to manifest openly their hostility to Mulla Husayn, they sought by every crafty

device to beguile the minds and damp the affections of his devoted admirers. Their

unseemly behaviour alienated the sympathy of the believers and precipitated their

separation from the company of the faithful. Expelled by their very acts from

the bosom of the Faith, they leagued themselves with its avowed enemies and proclaimed

their utter rejection of its claims and principles. So great was the mischief

which they stirred up among the people of that city that they were eventually

expelled by the civil authorities,

162

who alike despised and feared

their plottings. The Bab has in a Tablet, in which He expatiates upon their machinations

and misdeeds, compared them to the calf of the Samiri, the calf that had neither

voice nor soul, which was both the abject handiwork and the object of the adoration

of a wayward people. "May Thy condemnation, O God!" He wrote, with reference to

Mulla Javad and Mulla Abdu'l-'Ali, "rest upon the Jibt and Taghut,(1)

the twin idols of this perverse people." All three subsequently proceeded to Kirman

and joined forces with Haji Mirza Muhammad Karim Khan, whose designs they furthered

and the vehemence of whose denunciations they strove to reinforce.

One night after their expulsion

from Shiraz, the Bab, who was visiting the home of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, where

He had summoned to meet Him Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Nahri, Mirza Hadi, and Mulla

Abdu'l-Karim-i-Qazvini, turned suddenly to the last-named and said: " Abdu'l-Karim,

are you seeking the Manifestation?" These words, uttered with calm and extreme

gentleness, had a startling effect upon him. He paled at this sudden interrogation

and burst into tears. He threw himself at the feet of the Bab in a state of profound

agitation. The Bab took him lovingly in His arms, kissed his forehead, and invited

him to be seated by His side. In a tone of tender affection, He succeeded in appeasing

the tumult of his heart.

One night after their expulsion

from Shiraz, the Bab, who was visiting the home of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, where

He had summoned to meet Him Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Nahri, Mirza Hadi, and Mulla

Abdu'l-Karim-i-Qazvini, turned suddenly to the last-named and said: " Abdu'l-Karim,

are you seeking the Manifestation?" These words, uttered with calm and extreme

gentleness, had a startling effect upon him. He paled at this sudden interrogation

and burst into tears. He threw himself at the feet of the Bab in a state of profound

agitation. The Bab took him lovingly in His arms, kissed his forehead, and invited

him to be seated by His side. In a tone of tender affection, He succeeded in appeasing

the tumult of his heart.

As soon as they had regained their home, Mirza

Muhammad-'Ali and his brother enquired of Mulla Abdu'l-Karim the reason for the

violent perturbation which had suddenly seized him. "Hear me," he answered; "I

will relate to you the tale of a strange experience, a tale which I have shared

with no one until now. When I attained the age of maturity, I felt, while I lived

in Qazvin, a profound yearning to unravel the mystery of God and to apprehend

the nature of His saints and prophets. Nothing short of the acquisition of learning,

I realised, could enable me to achieve my goal. I succeeded in obtaining the consent

of my father and uncles to the abandonment of my business, and plunged immediately

into study and research. I occupied a room in one of the madrisihs of Qazvin,

and concentrated my efforts on the

As soon as they had regained their home, Mirza

Muhammad-'Ali and his brother enquired of Mulla Abdu'l-Karim the reason for the

violent perturbation which had suddenly seized him. "Hear me," he answered; "I

will relate to you the tale of a strange experience, a tale which I have shared

with no one until now. When I attained the age of maturity, I felt, while I lived

in Qazvin, a profound yearning to unravel the mystery of God and to apprehend

the nature of His saints and prophets. Nothing short of the acquisition of learning,

I realised, could enable me to achieve my goal. I succeeded in obtaining the consent

of my father and uncles to the abandonment of my business, and plunged immediately

into study and research. I occupied a room in one of the madrisihs of Qazvin,

and concentrated my efforts on the

163

acquisition of every available

branch of human learning. I often discussed the knowledge which I acquired with

my fellow-disciples, and sought by this means to enrich my experience. At night,

I would retire to my home, and, in the seclusion of my library, would devote many

an hour to undisturbed study. I was so immersed in my labours that I grew indifferent

to both sleep and hunger. Within two years I had resolved to master the intricacies

of Muslim jurisprudence and theology. I was a faithful attendant at the lectures

given by Mulla Abdu'l-Karim-i-Iravani, who, in those days, ranked as the most

outstanding divine of Qazvin. I greatly admired his vast erudition, his piety

and virtue. Every night during the period that I was his disciple, I devoted my

time to the writing of a treatise which I submitted to him and which he revised

with care and interest. He seemed to be greatly pleased with my progress, and

often extolled my high attainments. One day, in the presence of his assembled

disciples, he declared: `The learned and sagacious Mulla Abdu'l-Karim has qualified

himself to expound authoritatively the sacred Scriptures of Islam. He no longer

needs to attend either my classes or those of my equals. I shall, please God,

celebrate his elevation to the rank of a mujtahid on the morning of the coming

Friday, and will deliver his certificate to him after the congregational prayer.'

"No sooner had Mulla Abdu'l-Karim spoken these

words and departed than his disciples came forward and heartily congratulated

me on my accomplishments. I returned, greatly elated, to my home. Upon my arrival

I discovered that both my father and my elder uncle, Haji Husayn-'Ali, both of

whom were greatly esteemed throughout Qazvin, were preparing a feast in my honour,

with which they intended to celebrate the completion of my studies. I requested

them to postpone the invitation they had extended to the notables of Qazvin until

further notice from me. They gladly consented, believing that in my eagerness

for such a festival I would not unduly postpone it. That night I repaired to my

library and, in the privacy of my cell, pondered the following thoughts in my

heart: Had you not fondly imagined, I said to myself, that only the sanctified

in spirit could ever hope to attain the station of an authoritative expounder

of the

"No sooner had Mulla Abdu'l-Karim spoken these

words and departed than his disciples came forward and heartily congratulated

me on my accomplishments. I returned, greatly elated, to my home. Upon my arrival

I discovered that both my father and my elder uncle, Haji Husayn-'Ali, both of

whom were greatly esteemed throughout Qazvin, were preparing a feast in my honour,

with which they intended to celebrate the completion of my studies. I requested

them to postpone the invitation they had extended to the notables of Qazvin until

further notice from me. They gladly consented, believing that in my eagerness

for such a festival I would not unduly postpone it. That night I repaired to my

library and, in the privacy of my cell, pondered the following thoughts in my

heart: Had you not fondly imagined, I said to myself, that only the sanctified

in spirit could ever hope to attain the station of an authoritative expounder

of the

164

sacred Scriptures of Islam?

Was it not your belief that whoso attained this station would be immune from error?

Are you not already accounted among those who enjoy that rank? Has not Qazvin's

most distinguished divine recognised and declared you to be such? Be fair. Do

you in your own heart regard yourself as having attained that state of purity

and sublime detachment which you, in days past, considered the requisites for

one who aspires to reach that exalted position? Think you yourself to be free

from every taint of selfish desire? As I sat musing, a feeling of my own unworthiness

gradually overpowered me. I recognised myself as still a victim of cares and perplexities,

of temptations and doubts. I was oppressed by such thoughts as to how I should

conduct my classes, how to lead my congregation in prayer, how to enforce the

laws and precepts of the Faith. I felt continually anxious as to how I should

discharge my duties, how to ensure the superiority of my achievements over those

who had preceded me. I was overcome with such a sense of humiliation that I felt

impelled to seek forgiveness from God. Your aim in acquiring all this learning,

I thought to myself, has been to unravel the mystery of God and to attain the

state of certitude. Be fair. Are you sure of your own interpretation of the Qur'an?

Are you certain that the laws which you promulgate reflect the will of God? The

consciousness of error suddenly dawned upon me. I realised for the first time

how the rust of learning had corroded my soul and had obscured my vision. I lamented

my past, and deplored the futility of my endeavours. I knew that the people of

my own rank were subject to the same afflictions. As soon as they had acquired

this so-called learning, they would claim to be the exponents of the law of Islam

and would arrogate to themselves the exclusive privilege of pronouncing upon its

doctrine.

"I remained absorbed in my thoughts until

dawn. That night I neither ate nor slept. At times I would commune with God: `Thou

seest me, O my Lord, and Thou beholdest my plight. Thou knowest that I cherish

no other desire except Thy holy will and pleasure. I am lost in bewilderment at

the thought of the multitude of sects into which Thy holy Faith hath fallen. I

am deeply perplexed when I behold the

"I remained absorbed in my thoughts until

dawn. That night I neither ate nor slept. At times I would commune with God: `Thou

seest me, O my Lord, and Thou beholdest my plight. Thou knowest that I cherish

no other desire except Thy holy will and pleasure. I am lost in bewilderment at

the thought of the multitude of sects into which Thy holy Faith hath fallen. I

am deeply perplexed when I behold the

165

schisms that have torn the

religions of the past. Wilt Thou guide me in my perplexities, and relieve me of

my doubts? Whither am I to turn for consolation and guidance?' I wept so bitterly

that night that I seemed to have lost consciousness. There suddenly came to me

the vision of a great gathering of people, the expression of whose shining faces

greatly impressed me. A noble figure, attired in the garb of a siyyid, occupied

a seat on the pulpit facing the congregation. He was expounding the meaning of

this sacred verse of the Qur'an: `Whoso maketh efforts for Us, in Our ways will

We guide them.' I was fascinated by his face. I arose, advanced towards him, and

was on the point of throwing myself at his feet when that vision suddenly vanished.

My heart was flooded with light. My joy was indescribable.

"I immediately decided to consult Haji Allah-Vardi,

father of Muhammad-Javad-i-Farhadi, a man known throughout Qazvin for his deep

spiritual insight. When I related to him my vision, he smiled and with extraordinary

precision described to me the distinguishing features of the siyyid who had appeared

to me. `That noble figure,' he added, `was none other than Haji Siyyid Kazim-i-Rashti,

who is now in Karbila and who may be seen expounding every day to his disciples

the sacred teachings of Islam. Those who listen to his discourse are refreshed

and edified by his utterance. I can never describe the impression which his words

exert upon his hearers.' I joyously arose and, expressing to him my feelings of

profound appreciation, retired to my home and started forthwith on my journey

to Karbila. My old fellow-disciples came and entreated me either to call in person

on the learned Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, who had expressed a desire to meet me, or to

allow him to come to my house. `I feel the impulse,' I replied, `to visit the

shrine of the Imam Husayn at Karbila. I have vowed to start immediately on that

pilgrimage. I cannot postpone my departure. I will, if possible, visit him for

a few moments when I start to leave the city. If I cannot, I would beg him to

excuse me and to pray in my behalf that I may be guided on the straight path.'

"I immediately decided to consult Haji Allah-Vardi,

father of Muhammad-Javad-i-Farhadi, a man known throughout Qazvin for his deep

spiritual insight. When I related to him my vision, he smiled and with extraordinary

precision described to me the distinguishing features of the siyyid who had appeared

to me. `That noble figure,' he added, `was none other than Haji Siyyid Kazim-i-Rashti,

who is now in Karbila and who may be seen expounding every day to his disciples

the sacred teachings of Islam. Those who listen to his discourse are refreshed

and edified by his utterance. I can never describe the impression which his words

exert upon his hearers.' I joyously arose and, expressing to him my feelings of

profound appreciation, retired to my home and started forthwith on my journey

to Karbila. My old fellow-disciples came and entreated me either to call in person

on the learned Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, who had expressed a desire to meet me, or to

allow him to come to my house. `I feel the impulse,' I replied, `to visit the

shrine of the Imam Husayn at Karbila. I have vowed to start immediately on that

pilgrimage. I cannot postpone my departure. I will, if possible, visit him for

a few moments when I start to leave the city. If I cannot, I would beg him to

excuse me and to pray in my behalf that I may be guided on the straight path.'

"I confidentially acquainted my relatives

with the nature of my vision and its interpretation. I informed them of my projected

visit to Karbila. My words to them that very day

"I confidentially acquainted my relatives

with the nature of my vision and its interpretation. I informed them of my projected

visit to Karbila. My words to them that very day

166

instilled the love of Siyyid

Kazim in their hearts. They felt greatly drawn to Haji Allah-Vardi, freely associated

with him, and became his fervent admirers.

"My brother, Abdu'l-Hamid [who later quaffed

the cup of martyrdom in Tihran], accompanied me on my journey to Karbila. There

I met Siyyid Kazim and was amazed to hear him discourse to his assembled disciples