OON after the arrival of Mulla Husayn at Shiraz, the voice of

the people rose again in protest against him. The fear and indignation of the

multitude were excited by the knowledge of his continued and intimate intercourse

with the Bab. "He again has come to our city," they clamoured; "he again has raised

the standard of revolt and is, together with his chief, contemplating a still

fiercer onslaught upon our time-honoured institutions." So grave and menacing

became the situation that the Bab instructed Mulla Husayn to regain, by way of

Yazd, his native province of Khurasan. He likewise dismissed the rest of His companions

who had gathered in Shiraz, and bade them return to Isfahan. He retained Mulla

Abdu'l-Karim, to whom He assigned the duty of transcribing His writings.

OON after the arrival of Mulla Husayn at Shiraz, the voice of

the people rose again in protest against him. The fear and indignation of the

multitude were excited by the knowledge of his continued and intimate intercourse

with the Bab. "He again has come to our city," they clamoured; "he again has raised

the standard of revolt and is, together with his chief, contemplating a still

fiercer onslaught upon our time-honoured institutions." So grave and menacing

became the situation that the Bab instructed Mulla Husayn to regain, by way of

Yazd, his native province of Khurasan. He likewise dismissed the rest of His companions

who had gathered in Shiraz, and bade them return to Isfahan. He retained Mulla

Abdu'l-Karim, to whom He assigned the duty of transcribing His writings.  These precautionary measures which the Bab

deemed wise to undertake, relieved Him from the immediate danger of violence from

the infuriated people of Shiraz, and served to lend a fresh impetus to the propagation

of His Faith beyond the limits of that city. His disciples, who had spread throughout

the length and breadth of the country, fearlessly proclaimed to the multitude

of their countrymen the regenerating power of the new-born Revelation. The fame

of the Bab had been noised abroad and had reached the ears of those who held the

highest seats of authority, both in the capital and throughout the provinces.(1)

A wave of passionate enquiry swayed the minds and hearts of both the leaders and

the

These precautionary measures which the Bab

deemed wise to undertake, relieved Him from the immediate danger of violence from

the infuriated people of Shiraz, and served to lend a fresh impetus to the propagation

of His Faith beyond the limits of that city. His disciples, who had spread throughout

the length and breadth of the country, fearlessly proclaimed to the multitude

of their countrymen the regenerating power of the new-born Revelation. The fame

of the Bab had been noised abroad and had reached the ears of those who held the

highest seats of authority, both in the capital and throughout the provinces.(1)

A wave of passionate enquiry swayed the minds and hearts of both the leaders and

the

Muhammad Shah(1)

himself was moved to ascertain the veracity of these reports and to enquire into

their nature. He delegated Siyyid Yahyay-i-Darabi,(2)

the most learned, the most eloquent, and the most influential of his subjects,

to interview the Bab and to report to him the results of his investigations. The

Shah had implicit confidence in his impartiality, in his competence and profound

spiritual insight. He occupied a position of such pre-eminence among the leading

figures in Persia that at whatever meeting he happened to be present, no matter

how great the number of the ecclesiastical leaders who attended it, he was invariably

its chief speaker. None would dare to assert his views in his presence. They all

reverently observed silence before him; all testified to his sagacity, his unsurpassed

knowledge and mature wisdom.

Muhammad Shah(1)

himself was moved to ascertain the veracity of these reports and to enquire into

their nature. He delegated Siyyid Yahyay-i-Darabi,(2)

the most learned, the most eloquent, and the most influential of his subjects,

to interview the Bab and to report to him the results of his investigations. The

Shah had implicit confidence in his impartiality, in his competence and profound

spiritual insight. He occupied a position of such pre-eminence among the leading

figures in Persia that at whatever meeting he happened to be present, no matter

how great the number of the ecclesiastical leaders who attended it, he was invariably

its chief speaker. None would dare to assert his views in his presence. They all

reverently observed silence before him; all testified to his sagacity, his unsurpassed

knowledge and mature wisdom.

In those days Siyyid Yahya was residing in

Tihran in the house of Mirza Lutf-'Ali, the Master of Ceremonies to the Shah,

as the honoured guest of his Imperial Majesty. The Shah confidentially signified

through Mirza Lutf-'Ali his desire and pleasure that Siyyid Yahya should proceed

to Shiraz and investigate the matter in person. "Tell him from us, commanded the

sovereign, "that inasmuch as we repose the utmost confidence in his integrity,

and admire his moral and intellectual standards, and regard him as the most suitable

among the divines of our realm, we expect him to proceed to Shiraz, to enquire

thoroughly into the episode of the Siyyid-i-Bab, and to inform us of the results

of his investigations; We shall then know what measures it behoves us to take."

In those days Siyyid Yahya was residing in

Tihran in the house of Mirza Lutf-'Ali, the Master of Ceremonies to the Shah,

as the honoured guest of his Imperial Majesty. The Shah confidentially signified

through Mirza Lutf-'Ali his desire and pleasure that Siyyid Yahya should proceed

to Shiraz and investigate the matter in person. "Tell him from us, commanded the

sovereign, "that inasmuch as we repose the utmost confidence in his integrity,

and admire his moral and intellectual standards, and regard him as the most suitable

among the divines of our realm, we expect him to proceed to Shiraz, to enquire

thoroughly into the episode of the Siyyid-i-Bab, and to inform us of the results

of his investigations; We shall then know what measures it behoves us to take."

Siyyid Yahya had been himself desirous of

obtaining first-hand knowledge of the claims of the Bab, but had been unable,

owing to adverse circumstances, to undertake the journey to Fars. The message

of Muhammad Shah decided him to carry out his long-cherished intention. Assuring

his sovereign of his readiness to comply with his wish, he immediately set out

for Shiraz.

Siyyid Yahya had been himself desirous of

obtaining first-hand knowledge of the claims of the Bab, but had been unable,

owing to adverse circumstances, to undertake the journey to Fars. The message

of Muhammad Shah decided him to carry out his long-cherished intention. Assuring

his sovereign of his readiness to comply with his wish, he immediately set out

for Shiraz.  On his way, he conceived the various questions

which he thought he would submit to the Bab. Upon the replies which the latter

gave to these questions would, in his view, depend the truth and validity of His

mission. Upon his arrival at Shiraz, he met Mulla Shaykh Ali, surnamed Azim, with

whom he had been intimately associated while in Khurasan. He asked him whether

he was satisfied with his interview with the Bab. "You should meet Him," Azim

replied, "and seek independently to acquaint yourself with His Mission. As a friend,

I would advise you to exercise the utmost consideration

On his way, he conceived the various questions

which he thought he would submit to the Bab. Upon the replies which the latter

gave to these questions would, in his view, depend the truth and validity of His

mission. Upon his arrival at Shiraz, he met Mulla Shaykh Ali, surnamed Azim, with

whom he had been intimately associated while in Khurasan. He asked him whether

he was satisfied with his interview with the Bab. "You should meet Him," Azim

replied, "and seek independently to acquaint yourself with His Mission. As a friend,

I would advise you to exercise the utmost consideration

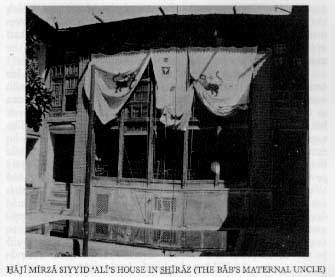

Siyyid Yahya met the Bab at

the home of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, and exercised in his attitude towards Him the

courtesy which Azim had counselled him to observe. For about two hours he directed

the attention of the Bab to the most abstruse and bewildering themes in the metaphysical

teachings of Islam, to the obscurest passages of the Qur'an, and to the mysterious

traditions and prophecies of the imams of the Faith. The Bab at first listened

to his learned references to the law and prophecies of Islam, noted all his questions,

and began to give to each a brief but persuasive reply. The conciseness and lucidity

of His answers excited the wonder and admiration of Siyyid Yahya. He was overpowered

by a sense of humiliation at his own presumptuousness and pride. His sense of

superiority completely vanished. As he arose to depart, he addressed the Bab in

these words: "Please God, I shall, in the course of my next audience with You,

submit the rest of my questions and with them shall conclude my enquiry." As soon

as he retired, he joined Azim, to whom he related the account of his interview.

"I have in His presence," he told him, "expatiated unduly upon my own learning.

He was able in a few words to answer my questions and to resolve my perplexities.

I felt so abased before Him that I hurriedly begged leave to retire." Azim reminded

him of his counsel, and begged him not to forget this time the advice he had given

him.

Siyyid Yahya met the Bab at

the home of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali, and exercised in his attitude towards Him the

courtesy which Azim had counselled him to observe. For about two hours he directed

the attention of the Bab to the most abstruse and bewildering themes in the metaphysical

teachings of Islam, to the obscurest passages of the Qur'an, and to the mysterious

traditions and prophecies of the imams of the Faith. The Bab at first listened

to his learned references to the law and prophecies of Islam, noted all his questions,

and began to give to each a brief but persuasive reply. The conciseness and lucidity

of His answers excited the wonder and admiration of Siyyid Yahya. He was overpowered

by a sense of humiliation at his own presumptuousness and pride. His sense of

superiority completely vanished. As he arose to depart, he addressed the Bab in

these words: "Please God, I shall, in the course of my next audience with You,

submit the rest of my questions and with them shall conclude my enquiry." As soon

as he retired, he joined Azim, to whom he related the account of his interview.

"I have in His presence," he told him, "expatiated unduly upon my own learning.

He was able in a few words to answer my questions and to resolve my perplexities.

I felt so abased before Him that I hurriedly begged leave to retire." Azim reminded

him of his counsel, and begged him not to forget this time the advice he had given

him.  In the course of his second interview, Siyyid

Yahya, to his amazement, discovered that all the questions which he had intended

to submit to the Bab had vanished from his memory. He contented himself with matters

that seemed irrelevant to the object of his enquiry. He soon found, to his still

greater surprise, that the Bab was answering, with the same lucidity and conciseness

that had characterised His previous replies, those same questions which he had

momentarily forgotten. "I seemed to have fallen fast asleep," he later observed.

"His words, His answers to questions which I had forgotten to ask, reawakened

me. A voice still kept whispering in my ear: `Might not this, after all, have

In the course of his second interview, Siyyid

Yahya, to his amazement, discovered that all the questions which he had intended

to submit to the Bab had vanished from his memory. He contented himself with matters

that seemed irrelevant to the object of his enquiry. He soon found, to his still

greater surprise, that the Bab was answering, with the same lucidity and conciseness

that had characterised His previous replies, those same questions which he had

momentarily forgotten. "I seemed to have fallen fast asleep," he later observed.

"His words, His answers to questions which I had forgotten to ask, reawakened

me. A voice still kept whispering in my ear: `Might not this, after all, have

"I resolved that in my third interview with

the Bab I would in my inmost heart request Him to reveal for me a commentary on

the Surih of Kawthar.(1) I

determined not to breathe that request in His presence. Should he, unasked by

me, reveal this commentary in a manner that would immediately distinguish it in

my eyes from the prevailing standards current among the commentators on the Qur'an,

I then would be convinced of the Divine character of His Mission, and would readily

embrace His Cause. If not, I would refuse to acknowledge Him. As soon as I was

ushered into His presence, a sense of fear, for which I could not account, suddenly

seized me. My limbs quivered as I beheld His face. I, who on repeated occasions

had been introduced into the presence of the Shah and had never discovered the

slightest trace of timidity in myself, was now so awed and shaken that I could

not remain standing on my feet. The Bab, beholding my plight, arose from His seat,

advanced towards me, and, taking hold of my hand, seated me beside Him. `Seek

from Me,' He said, `whatever is your heart's desire. I will readily reveal it

to you.' I was speechless with wonder. Like a babe that can neither understand

nor speak, I felt powerless to respond. He smiled as He gazed at me and said:

`Were I to reveal for you the commentary on the Surih of Kawthar, would you acknowledge

that My words are born of the Spirit of God? Would you recognise that My utterance

can in no wise be associated with sorcery or magic?' Tears flowed from my eyes

as I heard Him speak these words.

"I resolved that in my third interview with

the Bab I would in my inmost heart request Him to reveal for me a commentary on

the Surih of Kawthar.(1) I

determined not to breathe that request in His presence. Should he, unasked by

me, reveal this commentary in a manner that would immediately distinguish it in

my eyes from the prevailing standards current among the commentators on the Qur'an,

I then would be convinced of the Divine character of His Mission, and would readily

embrace His Cause. If not, I would refuse to acknowledge Him. As soon as I was

ushered into His presence, a sense of fear, for which I could not account, suddenly

seized me. My limbs quivered as I beheld His face. I, who on repeated occasions

had been introduced into the presence of the Shah and had never discovered the

slightest trace of timidity in myself, was now so awed and shaken that I could

not remain standing on my feet. The Bab, beholding my plight, arose from His seat,

advanced towards me, and, taking hold of my hand, seated me beside Him. `Seek

from Me,' He said, `whatever is your heart's desire. I will readily reveal it

to you.' I was speechless with wonder. Like a babe that can neither understand

nor speak, I felt powerless to respond. He smiled as He gazed at me and said:

`Were I to reveal for you the commentary on the Surih of Kawthar, would you acknowledge

that My words are born of the Spirit of God? Would you recognise that My utterance

can in no wise be associated with sorcery or magic?' Tears flowed from my eyes

as I heard Him speak these words.

"It was still early in the afternoon when

the Bab requested Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali to bring His pen-case and some paper.

He then started to reveal His commentary on the Surih of Kawthar. How am I to

describe this scene of inexpressible majesty? Verses streamed from His pen with

a rapidity that was truly astounding. The incredible swiftness of His writing,(1)

the soft and gentle murmur of His voice, and the stupendous force of His style,

amazed and bewildered me. He continued in this manner until the approach of sunset.

He did not pause until the entire commentary of the Surih was completed. He then

laid down His pen and asked for tea. Soon after, He began to read it aloud in

my presence. My heart leaped madly as I heard Him pour out, in accents of unutterable

sweetness, those treasures enshrined in that sublime commentary.(2)

I was so entranced by its beauty that three times over I was on the verge of fainting.

He sought to revive my failing strength with a few drops of rose-water which He

caused to be sprinkled on my face. This

"It was still early in the afternoon when

the Bab requested Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali to bring His pen-case and some paper.

He then started to reveal His commentary on the Surih of Kawthar. How am I to

describe this scene of inexpressible majesty? Verses streamed from His pen with

a rapidity that was truly astounding. The incredible swiftness of His writing,(1)

the soft and gentle murmur of His voice, and the stupendous force of His style,

amazed and bewildered me. He continued in this manner until the approach of sunset.

He did not pause until the entire commentary of the Surih was completed. He then

laid down His pen and asked for tea. Soon after, He began to read it aloud in

my presence. My heart leaped madly as I heard Him pour out, in accents of unutterable

sweetness, those treasures enshrined in that sublime commentary.(2)

I was so entranced by its beauty that three times over I was on the verge of fainting.

He sought to revive my failing strength with a few drops of rose-water which He

caused to be sprinkled on my face. This

"When He had completed His recital, the Bab

arose to depart. He entrusted me, as He left, to the care of His maternal uncle.

`He is to be your guest,' He told him, `until the time when he, in collaboration

with Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, shall have finished transcribing this newly revealed

commentary, and shall have verified the correctness of the transcribed copy.'

Mulla Abdu'l-Karim and I devoted three days and three nights to this work. We

would in turn read aloud to each other a portion of the commentary until the whole

of it had been transcribed. We verified all the traditions in the text and found

them to be entirely accurate. Such was the state of certitude to which I had attained

that if all the powers of the earth were to be leagued against me they would be

powerless to shake my confidence in the greatness of His Cause.(1)

"When He had completed His recital, the Bab

arose to depart. He entrusted me, as He left, to the care of His maternal uncle.

`He is to be your guest,' He told him, `until the time when he, in collaboration

with Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, shall have finished transcribing this newly revealed

commentary, and shall have verified the correctness of the transcribed copy.'

Mulla Abdu'l-Karim and I devoted three days and three nights to this work. We

would in turn read aloud to each other a portion of the commentary until the whole

of it had been transcribed. We verified all the traditions in the text and found

them to be entirely accurate. Such was the state of certitude to which I had attained

that if all the powers of the earth were to be leagued against me they would be

powerless to shake my confidence in the greatness of His Cause.(1)

"As I had, since my arrival at Shiraz, been

living in the home of Husayn Khan, the governor of Fars, I felt that my prolonged

absence from his house might excite his suspicion and inflame his anger. I therefore

determined to take leave of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali and Mulla Abdu'l-Karim and to

regain the residence of the governor. On my arrival I found that Husayn Khan,

who in the meantime had been searching for me, was eager to know whether I had

fallen a victim to the Bab's magic influence. `No one but God,' I replied, `who

alone can change the hearts of men, is able to captivate the heart of Siyyid Yahya.

Whoso can ensnare his heart is of God, and His word unquestionably the voice of

Truth.' My answer silenced the governor. In his conversation with others, I subsequently

learned, he had expressed the view that I too had fallen a hopeless victim to

the charm of that Youth. He had even written to Muhammad Shah and complained that

during my stay in Shiraz I had refused all manner of intercourse with the ulamas

of the city. `Though nominally my guest,' he wrote to his sovereign, `he frequently

"As I had, since my arrival at Shiraz, been

living in the home of Husayn Khan, the governor of Fars, I felt that my prolonged

absence from his house might excite his suspicion and inflame his anger. I therefore

determined to take leave of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali and Mulla Abdu'l-Karim and to

regain the residence of the governor. On my arrival I found that Husayn Khan,

who in the meantime had been searching for me, was eager to know whether I had

fallen a victim to the Bab's magic influence. `No one but God,' I replied, `who

alone can change the hearts of men, is able to captivate the heart of Siyyid Yahya.

Whoso can ensnare his heart is of God, and His word unquestionably the voice of

Truth.' My answer silenced the governor. In his conversation with others, I subsequently

learned, he had expressed the view that I too had fallen a hopeless victim to

the charm of that Youth. He had even written to Muhammad Shah and complained that

during my stay in Shiraz I had refused all manner of intercourse with the ulamas

of the city. `Though nominally my guest,' he wrote to his sovereign, `he frequently

" Muhammad Shah himself, at one of the state

functions in his capital, was reported to have addressed these words to Haji Mirza

Aqasi: `We have been lately informed(1)

that Siyyid Yahyay-i-Darabi has become a Babi. If this be true, it behoves us

to cease belittling the cause of that siyyid.' Husayn Khan, on his part, received

the following imperial command: `It is strictly forbidden to any one of our subjects

to utter such words as would tend to detract from the exalted rank of Siyyid Yahyay-i-Darabi.

He is of noble lineage, a man of great learning, of perfect and consummate virtue.

He will under no circumstances incline his ear to any cause unless he believes

it to be conducive to the advancement of the best interests of our realm and to

the well-being of the Faith of Islam.'

" Muhammad Shah himself, at one of the state

functions in his capital, was reported to have addressed these words to Haji Mirza

Aqasi: `We have been lately informed(1)

that Siyyid Yahyay-i-Darabi has become a Babi. If this be true, it behoves us

to cease belittling the cause of that siyyid.' Husayn Khan, on his part, received

the following imperial command: `It is strictly forbidden to any one of our subjects

to utter such words as would tend to detract from the exalted rank of Siyyid Yahyay-i-Darabi.

He is of noble lineage, a man of great learning, of perfect and consummate virtue.

He will under no circumstances incline his ear to any cause unless he believes

it to be conducive to the advancement of the best interests of our realm and to

the well-being of the Faith of Islam.'  "Upon the receipt of this imperial injunction,

Husayn Khan, unable to resist me openly, strove privily to undermine my authority.

His face betrayed an implacable enmity and hate. He failed, however, in view of

the marked favours bestowed upon me by the Shah, either to harm my person or to

discredit my name.

"Upon the receipt of this imperial injunction,

Husayn Khan, unable to resist me openly, strove privily to undermine my authority.

His face betrayed an implacable enmity and hate. He failed, however, in view of

the marked favours bestowed upon me by the Shah, either to harm my person or to

discredit my name.  "I was subsequently commanded by the Bab to

journey to Burujird, and there acquaint my father(2)

with the new Message. He urged me to exercise towards him the utmost forbearance

and consideration. From my confidential conversations with him I gathered that

he was unwilling to repudiate the truth of the Message I had brought him. He preferred,

however, to be left alone and to be allowed to pursue his own way."

"I was subsequently commanded by the Bab to

journey to Burujird, and there acquaint my father(2)

with the new Message. He urged me to exercise towards him the utmost forbearance

and consideration. From my confidential conversations with him I gathered that

he was unwilling to repudiate the truth of the Message I had brought him. He preferred,

however, to be left alone and to be allowed to pursue his own way."  Another dignitary of the realm

who dispassionately investigated and ultimately embraced the Message of the Bab

Another dignitary of the realm

who dispassionately investigated and ultimately embraced the Message of the Bab

As soon as the Call from Shiraz reached his

ears, Hujjat deputed one of his disciples, Mulla Iskandar, in whom he reposed

the fullest confidence, to enquire into the whole matter and to report to him

the result of his investigations. Utterly indifferent to the praise and censure

of his countrymen, whose integrity he suspected and whose judgment he disdained,

he sent his delegate to Shiraz with explicit instructions to conduct a minute

and independent enquiry. Mulla Iskandar attained the presence of the Bab and felt

immediately the regenerating power of His influence. He tarried

As soon as the Call from Shiraz reached his

ears, Hujjat deputed one of his disciples, Mulla Iskandar, in whom he reposed

the fullest confidence, to enquire into the whole matter and to report to him

the result of his investigations. Utterly indifferent to the praise and censure

of his countrymen, whose integrity he suspected and whose judgment he disdained,

he sent his delegate to Shiraz with explicit instructions to conduct a minute

and independent enquiry. Mulla Iskandar attained the presence of the Bab and felt

immediately the regenerating power of His influence. He tarried

With the approval of the Bab, he returned

to Zanjan. He arrived at a time when all the leading ulamas of the city had assembled

in the presence of Hujjat. As soon as he appeared, Hujjat enquired whether he

believed in, or rejected, the new Revelation. Mulla Iskandar submitted the writings

of the Bab which he had brought with him, and asserted that whatever should be

the verdict of his master, the same would he deem it his obligation to follow.

"What!" angrily exclaimed Hujjat. "But for the presence of this distinguished

company; I would have chastised you severely. How dare you consider matters of

belief to be dependent upon the approbation or rejection of others?" Receiving

from the hand of his messenger the copy of the Qayyumu'l-Asma', he, as soon as

he had perused a page of that book, fell prostrate upon the ground and exclaimed

"I bear witness that these words which I have read proceed from the same Source

as that of the Qur'an. Whoso has recognised the truth of that sacred Book must

needs testify to the Divine origin of these words, and must needs submit to the

precepts inculcated by their Author. I take you, members of this assembly, as

my witnesses: I pledge such allegiance to the Author of this Revelation that should

He ever pronounce the night to be the day, and declare the sun to be a shadow,

I would unreservedly submit to His judgment, and would regard His verdict as the

voice of Truth. Whoso denies Him, him will I regard as the repudiator of God Himself."

With these words he terminated the proceedings of that gathering.(1)

With the approval of the Bab, he returned

to Zanjan. He arrived at a time when all the leading ulamas of the city had assembled

in the presence of Hujjat. As soon as he appeared, Hujjat enquired whether he

believed in, or rejected, the new Revelation. Mulla Iskandar submitted the writings

of the Bab which he had brought with him, and asserted that whatever should be

the verdict of his master, the same would he deem it his obligation to follow.

"What!" angrily exclaimed Hujjat. "But for the presence of this distinguished

company; I would have chastised you severely. How dare you consider matters of

belief to be dependent upon the approbation or rejection of others?" Receiving

from the hand of his messenger the copy of the Qayyumu'l-Asma', he, as soon as

he had perused a page of that book, fell prostrate upon the ground and exclaimed

"I bear witness that these words which I have read proceed from the same Source

as that of the Qur'an. Whoso has recognised the truth of that sacred Book must

needs testify to the Divine origin of these words, and must needs submit to the

precepts inculcated by their Author. I take you, members of this assembly, as

my witnesses: I pledge such allegiance to the Author of this Revelation that should

He ever pronounce the night to be the day, and declare the sun to be a shadow,

I would unreservedly submit to His judgment, and would regard His verdict as the

voice of Truth. Whoso denies Him, him will I regard as the repudiator of God Himself."

With these words he terminated the proceedings of that gathering.(1)

We have, in the preceding

pages, referred to the expulsion of Quddus and of Mulla Sadiq from Shiraz, and

have attempted to describe, however inadequately, the chastisement inflicted upon

them by the tyrannical and rapacious Husayn

We have, in the preceding

pages, referred to the expulsion of Quddus and of Mulla Sadiq from Shiraz, and

have attempted to describe, however inadequately, the chastisement inflicted upon

them by the tyrannical and rapacious Husayn

The siyyid's message stung Haji Mirza Karim

Khan. Convulsed by a feeling of intense resentment which he could neither suppress

nor gratify, he relinquished all hopes of acquiring the undisputed leadership

of the people of Kirman. That open challenge sounded the death-knell of his cherished

ambitions.

The siyyid's message stung Haji Mirza Karim

Khan. Convulsed by a feeling of intense resentment which he could neither suppress

nor gratify, he relinquished all hopes of acquiring the undisputed leadership

of the people of Kirman. That open challenge sounded the death-knell of his cherished

ambitions.  In the privacy of his home, Haji Siyyid Javad

heard Quddus recount all the details of his activities from the day of his departure

from Karbila until his arrival at Kirman. The circumstances of his conversion

and his subsequent pilgrimage with the Bab stirred the imagination and kindled

the flame of faith in the heart of his host, who preferred, however, to conceal

his belief, in the hope of being able to guard more effectively the interests

of the newly established community. "Your noble resolve," Quddus lovingly assured

him, "will in itself be regarded as a notable service rendered to the

In the privacy of his home, Haji Siyyid Javad

heard Quddus recount all the details of his activities from the day of his departure

from Karbila until his arrival at Kirman. The circumstances of his conversion

and his subsequent pilgrimage with the Bab stirred the imagination and kindled

the flame of faith in the heart of his host, who preferred, however, to conceal

his belief, in the hope of being able to guard more effectively the interests

of the newly established community. "Your noble resolve," Quddus lovingly assured

him, "will in itself be regarded as a notable service rendered to the

The incident was related to me by a certain

Mirza Abdu'llah-i-Ghawgka, who, while in Kirman, had heard it from the lips of

Haji Siyyid Javad himself. The sincerity of the expressed intentions of the siyyid

has been fully vindicated by the splendid manner in which, as a result of his

endeavours,

The incident was related to me by a certain

Mirza Abdu'llah-i-Ghawgka, who, while in Kirman, had heard it from the lips of

Haji Siyyid Javad himself. The sincerity of the expressed intentions of the siyyid

has been fully vindicated by the splendid manner in which, as a result of his

endeavours,

From Kirman, Quddus decided

to leave for Yazd, and from thence to proceed to Ardikan, Nayin, Ardistan, Isfahan,

Kashan, Qum, and Tihran. In each of these cities, notwithstanding the obstacles

that beset his path, he succeeded in instilling into the understanding of his

hearers the principles which he had so bravely risen to advocate. I have

From Kirman, Quddus decided

to leave for Yazd, and from thence to proceed to Ardikan, Nayin, Ardistan, Isfahan,

Kashan, Qum, and Tihran. In each of these cities, notwithstanding the obstacles

that beset his path, he succeeded in instilling into the understanding of his

hearers the principles which he had so bravely risen to advocate. I have

In Tihran, Quddus was admitted

into the presence of Baha'u'llah after which he proceeded to Mazindaran, where,

in his native town of Barfurush, in the home of his father, he lived for about

two years, during which time he was surrounded by the loving devotion of his family

and kindred. His father had married, on the death of his first wife, a lady who

treated Quddus with a kindness and care that no mother could have hoped to surpass.

She longed to witness his wedding, and was often heard to express her fears lest

she should have to carry with her to the grave the "supreme joy of her heart."

"The day of my wedding," Quddus observed, "is not yet come. That day will be unspeakably

glorious. Not within the confines of this house, but out in the open air, under

the vault of heaven, in the midst of the Sabzih-Maydan, before the gaze of the

multitude, there shall I celebrate my nuptials and witness the consummation of

my hopes." Three years later, when that lady learned of the circumstances attending

the martyrdom of Quddus in the Sabzih-Maydan, she recalled his prophetic words

and understood their meaning.(1)

Quddus remained in Barfurush until the time when he was joined by Mulla Husayn

after the latter's return from his visit to the Bab in the castle of Mah-Ku. From

Barfurush they set out for Khurasan, a journey rendered memorable by deeds so

heroic that none of their countrymen could hope to rival them.

In Tihran, Quddus was admitted

into the presence of Baha'u'llah after which he proceeded to Mazindaran, where,

in his native town of Barfurush, in the home of his father, he lived for about

two years, during which time he was surrounded by the loving devotion of his family

and kindred. His father had married, on the death of his first wife, a lady who

treated Quddus with a kindness and care that no mother could have hoped to surpass.

She longed to witness his wedding, and was often heard to express her fears lest

she should have to carry with her to the grave the "supreme joy of her heart."

"The day of my wedding," Quddus observed, "is not yet come. That day will be unspeakably

glorious. Not within the confines of this house, but out in the open air, under

the vault of heaven, in the midst of the Sabzih-Maydan, before the gaze of the

multitude, there shall I celebrate my nuptials and witness the consummation of

my hopes." Three years later, when that lady learned of the circumstances attending

the martyrdom of Quddus in the Sabzih-Maydan, she recalled his prophetic words

and understood their meaning.(1)

Quddus remained in Barfurush until the time when he was joined by Mulla Husayn

after the latter's return from his visit to the Bab in the castle of Mah-Ku. From

Barfurush they set out for Khurasan, a journey rendered memorable by deeds so

heroic that none of their countrymen could hope to rival them.  As to Mulla Sadiq, as soon as he arrived at

Yazd, he enquired of a trusted friend, a native of Khurasan, about the

As to Mulla Sadiq, as soon as he arrived at

Yazd, he enquired of a trusted friend, a native of Khurasan, about the

" Mirza Ahmad," he was told, "secluded himself

for a considerable period of time in his own home, and there concentrated his

energies upon the preparation of a learned and voluminous compilation of Islamic

traditions and prophecies relating to the time and the character of the promised

Dispensation. He collected more than twelve thousand traditions of the most explicit

character, the authenticity of which was universally recognised; and resolved

to take whatever steps were required for the copying and the dissemination of

that book. By encouraging his fellow-disciples to quote publicly from its contents,

in all congregations and gatherings, he hoped he would be able to remove such

hindrances as might impede the progress of the Cause he had at heart.

" Mirza Ahmad," he was told, "secluded himself

for a considerable period of time in his own home, and there concentrated his

energies upon the preparation of a learned and voluminous compilation of Islamic

traditions and prophecies relating to the time and the character of the promised

Dispensation. He collected more than twelve thousand traditions of the most explicit

character, the authenticity of which was universally recognised; and resolved

to take whatever steps were required for the copying and the dissemination of

that book. By encouraging his fellow-disciples to quote publicly from its contents,

in all congregations and gatherings, he hoped he would be able to remove such

hindrances as might impede the progress of the Cause he had at heart.  "When he

arrived at Yazd, he was warmly welcomed by his maternal uncle, Siyyid Husayn-i-Azghandi,

the foremost mujtahid of that city, who, a few days before the arrival of his

nephew, had sent him a written request to hasten to Yazd and deliver him from

the machinations of Haji Mirza Karim Khan, whom he regarded as a dangerous though

unavowed enemy of Islam. The mujtahid called upon Mirza Ahmad to combat by every

means in his power Haji Mirza Khan's pernicious influence; and wished him to establish

permanently his residence in that city, that he might, through incessant exhortations

and appeals, succeed in enlightening the minds of the people as to the true aims

and intentions cherished by that malignant enemy.

"When he

arrived at Yazd, he was warmly welcomed by his maternal uncle, Siyyid Husayn-i-Azghandi,

the foremost mujtahid of that city, who, a few days before the arrival of his

nephew, had sent him a written request to hasten to Yazd and deliver him from

the machinations of Haji Mirza Karim Khan, whom he regarded as a dangerous though

unavowed enemy of Islam. The mujtahid called upon Mirza Ahmad to combat by every

means in his power Haji Mirza Khan's pernicious influence; and wished him to establish

permanently his residence in that city, that he might, through incessant exhortations

and appeals, succeed in enlightening the minds of the people as to the true aims

and intentions cherished by that malignant enemy.  " Mirza Ahmad, concealing from his uncle his

original intention to leave for Shiraz, decided to prolong his stay in Yazd. He

showed him the book which he had compiled, and shared its contents with the ulamas

who thronged from every quarter of the city to meet him. All were greatly impressed

" Mirza Ahmad, concealing from his uncle his

original intention to leave for Shiraz, decided to prolong his stay in Yazd. He

showed him the book which he had compiled, and shared its contents with the ulamas

who thronged from every quarter of the city to meet him. All were greatly impressed

"Among those who came to visit Mirza Ahmad

was a certain Mirza Taqi, a man who was wicked, ambitious, and haughty, who had

recently returned from Najaf, where he had completed his studies and had been

elevated to the rank of mujtahid. In the course of his conversation with Mirza

Ahmad, he expressed a desire to peruse that book, and to be allowed to retain

it for a few days, that he might acquire a fuller understanding of its contents.

Siyyid Husayn and his nephew both acceded to his wish. Mirza Taqi, who was to

have returned the book, failed to redeem his promise. Mirza Ahmad, who had already

suspected the insincerity of Mirza Taqi's intentions, urged his uncle to remind

the borrower of the pledge he had given. `Tell your master,' was the insolent

reply to the messenger sent to claim the book, `that after having satisfied myself

as to the mischievous character of that compilation, I decided to destroy it.

Last night I threw it into the pond, thereby obliterating its pages.'

"Among those who came to visit Mirza Ahmad

was a certain Mirza Taqi, a man who was wicked, ambitious, and haughty, who had

recently returned from Najaf, where he had completed his studies and had been

elevated to the rank of mujtahid. In the course of his conversation with Mirza

Ahmad, he expressed a desire to peruse that book, and to be allowed to retain

it for a few days, that he might acquire a fuller understanding of its contents.

Siyyid Husayn and his nephew both acceded to his wish. Mirza Taqi, who was to

have returned the book, failed to redeem his promise. Mirza Ahmad, who had already

suspected the insincerity of Mirza Taqi's intentions, urged his uncle to remind

the borrower of the pledge he had given. `Tell your master,' was the insolent

reply to the messenger sent to claim the book, `that after having satisfied myself

as to the mischievous character of that compilation, I decided to destroy it.

Last night I threw it into the pond, thereby obliterating its pages.'  "Moved by deep and determined indignation

at such deceitfulness and impertinence, Siyyid Husayn resolved to wreak his vengeance

upon him. Mirza Ahmad succeeded, however, by his wise counsels, in pacifying the

anger of his infuriated uncle and in dissuading him from carrying out the measures

which he proposed to take. `This punishment,' he urged, `which you contemplate

will excite the agitation of the people, and will stir up mischief and sedition.

It will gravely interfere with the efforts which you wish me to exert in order

to extinguish the influence of Haji Mirza Karim Khan. He will undoubtedly seize

the occasion to denounce you as a Babi, and will hold me responsible for having

been the cause of your conversion. By this means he will both undermine your authority

and earn the esteem and gratitude of the people. Leave him in the hands of God.'"

"Moved by deep and determined indignation

at such deceitfulness and impertinence, Siyyid Husayn resolved to wreak his vengeance

upon him. Mirza Ahmad succeeded, however, by his wise counsels, in pacifying the

anger of his infuriated uncle and in dissuading him from carrying out the measures

which he proposed to take. `This punishment,' he urged, `which you contemplate

will excite the agitation of the people, and will stir up mischief and sedition.

It will gravely interfere with the efforts which you wish me to exert in order

to extinguish the influence of Haji Mirza Karim Khan. He will undoubtedly seize

the occasion to denounce you as a Babi, and will hold me responsible for having

been the cause of your conversion. By this means he will both undermine your authority

and earn the esteem and gratitude of the people. Leave him in the hands of God.'"

Mulla Sadiq was greatly pleased to learn from

the account of this incident that Mirza Ahmad was actually residing in Yazd, and

that no obstacles stood in the way of his meeting with him. He went immediately

to the masjid in which Siyyid Husayn was leading the congregational prayer and

in which

Mulla Sadiq was greatly pleased to learn from

the account of this incident that Mirza Ahmad was actually residing in Yazd, and

that no obstacles stood in the way of his meeting with him. He went immediately

to the masjid in which Siyyid Husayn was leading the congregational prayer and

in which

Mulla Sadiq prefaced his discourse with one

of the best-known and most exquisitely written homilies of the Bab, after which

he addressed the congregation in these terms: "Render thanks to God, O people

of learning, for, behold, the Gate of Divine Knowledge, which you deem to have

been closed, is now wide open. The River of everlasting life has streamed forth

from the city of Shiraz, and is conferring untold blessings upon the people of

this land. Whoever has partaken of one drop from this Ocean of heavenly grace,

no matter how humble and unlettered, has discovered in himself the power to unravel

the profoundest mysteries, and has felt capable of expounding the most abstruse

themes of ancient wisdom. And whoever,though he be the most learned expounder

of the Faith of Islam, has chosen to rely upon his own competence and power and

has disdained the Message of God, has condemned himself to irretrievable degradation

and loss."

Mulla Sadiq prefaced his discourse with one

of the best-known and most exquisitely written homilies of the Bab, after which

he addressed the congregation in these terms: "Render thanks to God, O people

of learning, for, behold, the Gate of Divine Knowledge, which you deem to have

been closed, is now wide open. The River of everlasting life has streamed forth

from the city of Shiraz, and is conferring untold blessings upon the people of

this land. Whoever has partaken of one drop from this Ocean of heavenly grace,

no matter how humble and unlettered, has discovered in himself the power to unravel

the profoundest mysteries, and has felt capable of expounding the most abstruse

themes of ancient wisdom. And whoever,though he be the most learned expounder

of the Faith of Islam, has chosen to rely upon his own competence and power and

has disdained the Message of God, has condemned himself to irretrievable degradation

and loss."  A wave of indignation and dismay swept over

the entire congregation as these words of Mulla Sadiq pealed out this momentous

announcement. The masjid rang with cries of "Blasphemy!" which an infuriated congregation

shouted in horror against the speaker. "Descend from the pulpit," rose the voice

of Siyyid Husayn amid the clamour and tumult of the people, as he motioned to

Mulla Sadiq to hold his peace and to retire. No sooner had he regained the floor

of the masjid than the whole company of the assembled worshippers rushed upon

him and overwhelmed him with blows. Siyyid Husayn immediately intervened, vigorously

dispersed the crowd, and, seizing the hand of Mulla Sadiq, forcibly drew him to

his side. "Withhold your hands," he appealed to the multitude; "leave him in my

custody. I will take him

A wave of indignation and dismay swept over

the entire congregation as these words of Mulla Sadiq pealed out this momentous

announcement. The masjid rang with cries of "Blasphemy!" which an infuriated congregation

shouted in horror against the speaker. "Descend from the pulpit," rose the voice

of Siyyid Husayn amid the clamour and tumult of the people, as he motioned to

Mulla Sadiq to hold his peace and to retire. No sooner had he regained the floor

of the masjid than the whole company of the assembled worshippers rushed upon

him and overwhelmed him with blows. Siyyid Husayn immediately intervened, vigorously

dispersed the crowd, and, seizing the hand of Mulla Sadiq, forcibly drew him to

his side. "Withhold your hands," he appealed to the multitude; "leave him in my

custody. I will take him

By this solemn assurance, Mulla Sadiq was

delivered from the savage attacks of his assailants. Divested of his aba(1)

and turban, deprived of his sandals and staff, bruised and shaken by the injuries

he had received, he was entrusted to the care of Siyyid Husayn's attendants, who,

as they forced their passage among the crowd, succeeded eventually in conducting

him to the home of their master.

By this solemn assurance, Mulla Sadiq was

delivered from the savage attacks of his assailants. Divested of his aba(1)

and turban, deprived of his sandals and staff, bruised and shaken by the injuries

he had received, he was entrusted to the care of Siyyid Husayn's attendants, who,

as they forced their passage among the crowd, succeeded eventually in conducting

him to the home of their master.  Mulla Yusuf-i-Ardibili, likewise, was subjected

in those days to a persecution fiercer and more determined than the savage onslaught

which the people of Yazd had directed against Mulla Sadiq. But for the intervention

of Mirza Ahmad and the assistance of his uncle, he would have fallen a victim

to the wrath of a ferocious enemy.

Mulla Yusuf-i-Ardibili, likewise, was subjected

in those days to a persecution fiercer and more determined than the savage onslaught

which the people of Yazd had directed against Mulla Sadiq. But for the intervention

of Mirza Ahmad and the assistance of his uncle, he would have fallen a victim

to the wrath of a ferocious enemy.  When Mulla Sadiq and Mulla Yusuf-i-Ardibili

arrived at Kirman, they again had to submit to similar indignities and to suffer

similar afflictions at the hands of Haji Mirza Karim Khan and his associates.(2)

Haji Siyyid Javad's persistent exertions freed them eventually from the grasp

of their persecutors, and enabled them to proceed to Khurasan.

When Mulla Sadiq and Mulla Yusuf-i-Ardibili

arrived at Kirman, they again had to submit to similar indignities and to suffer

similar afflictions at the hands of Haji Mirza Karim Khan and his associates.(2)

Haji Siyyid Javad's persistent exertions freed them eventually from the grasp

of their persecutors, and enabled them to proceed to Khurasan.  Though hunted and harassed by their foes,

the Bab's immediate disciples, together with their companions in different parts

of Persia, were undeterred by such criminal acts

Though hunted and harassed by their foes,

the Bab's immediate disciples, together with their companions in different parts

of Persia, were undeterred by such criminal acts

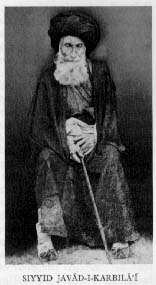

While Vahid(1)

was still in Shiraz, Haji Siyyid Javad-i-Karbila'i(2)

arrived and was introduced by Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali into the presence of the Bab.

In a Tablet which He addressed to Vahid and Haji Siyyid Javad, the Bab extolled

the firmness of their faith and stressed the unalterable character of their devotion.

The latter had met and known the Bab before the declaration of His Mission, and

had been a fervent admirer of those extraordinary traits of character which had

distinguished Him ever since His childhood. At a later time, he met Baha'u'llah

in Baghdad and became the recipient of His special favour. When, a few years afterwards,

Baha'u'llah was exiled to Adrianople, he, already much advanced in years, returned

to Persia, tarried awhile in the province of Iraq, and thence proceeded to Khurasan.

His kindly disposition, extreme forbearance, and unaffected simplicity earned

him the appellation of the Siyyid-i-Nur.(3)

While Vahid(1)

was still in Shiraz, Haji Siyyid Javad-i-Karbila'i(2)

arrived and was introduced by Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali into the presence of the Bab.

In a Tablet which He addressed to Vahid and Haji Siyyid Javad, the Bab extolled

the firmness of their faith and stressed the unalterable character of their devotion.

The latter had met and known the Bab before the declaration of His Mission, and

had been a fervent admirer of those extraordinary traits of character which had

distinguished Him ever since His childhood. At a later time, he met Baha'u'llah

in Baghdad and became the recipient of His special favour. When, a few years afterwards,

Baha'u'llah was exiled to Adrianople, he, already much advanced in years, returned

to Persia, tarried awhile in the province of Iraq, and thence proceeded to Khurasan.

His kindly disposition, extreme forbearance, and unaffected simplicity earned

him the appellation of the Siyyid-i-Nur.(3)

Haji Siyyid Javad, one day, while crossing

a street in Tihran, suddenly saw the Shah as he was passing on horseback. Undisturbed

by the presence of his sovereign, he calmly approached and greeted him. His venerable

figure and dignity of bearing pleased the Shah immensely. He acknowledged his

salute and invited him to come and see him. Such was the reception accorded him

that the courtiers of the Shah were moved with envy. "Does not your Imperial Majesty

realise," they protested, "that this Haji

Haji Siyyid Javad, one day, while crossing

a street in Tihran, suddenly saw the Shah as he was passing on horseback. Undisturbed

by the presence of his sovereign, he calmly approached and greeted him. His venerable

figure and dignity of bearing pleased the Shah immensely. He acknowledged his

salute and invited him to come and see him. Such was the reception accorded him

that the courtiers of the Shah were moved with envy. "Does not your Imperial Majesty

realise," they protested, "that this Haji

Siyyid

Javad is none other than the man who, even prior to the declaration of

the Siyyid-i-Bab, had proclaimed himself a Babi, and had pledged his undying

loyalty to his person?" The Shah, perceiving the malice which actuated

their accusation, was sorely displeased, and rebuked them for their temerity

and low-mindedness. "How strange!" he is reported to have exclaimed; "whoever

is distinguished by the uprightness of his conduct and the courtesy of

his manners, my people forthwith denounce him as a Babi and regard him

as an object worthy of my condemnation!"  Haji Siyyid Javad spent the last days

of his life in Kirman and remained until his last hour a staunch supporter

of the Faith. He never wavered in his convictions nor relaxed in his unsparing

endeavours for the diffusion of the Cause. Haji Siyyid Javad spent the last days

of his life in Kirman and remained until his last hour a staunch supporter

of the Faith. He never wavered in his convictions nor relaxed in his unsparing

endeavours for the diffusion of the Cause.  Shaykh Sultan-i-Karbila'i, whose ancestors

ranked among the leading ulamas of Karbila, and who himself had been a

firm supporter and intimate companion of Siyyid Kazim, was also among

those who, in those days, had met the Bab in Shiraz. It was he who, at

a later time, proceeded to Sulaymaniyyih in search of Baha'u'llah, and

whose daughter was subsequently given in marriage to Aqay-i-Kalim. When

he arrived at Shiraz, he was accompanied by Shaykh Hasan-i-Zunuzi, to

whom we have referred in the early pages of this narrative. To him the

Bab assigned the task of transcribing, in collaboration with Mulla Abdu'l-Karim,

the Tablets which He had lately revealed. Shaykh Sultan, who had been

too ill, at the time of his arrival, to meet the Bab, received one night,

while still on his sick-bed, a message from his Shaykh Sultan-i-Karbila'i, whose ancestors

ranked among the leading ulamas of Karbila, and who himself had been a

firm supporter and intimate companion of Siyyid Kazim, was also among

those who, in those days, had met the Bab in Shiraz. It was he who, at

a later time, proceeded to Sulaymaniyyih in search of Baha'u'llah, and

whose daughter was subsequently given in marriage to Aqay-i-Kalim. When

he arrived at Shiraz, he was accompanied by Shaykh Hasan-i-Zunuzi, to

whom we have referred in the early pages of this narrative. To him the

Bab assigned the task of transcribing, in collaboration with Mulla Abdu'l-Karim,

the Tablets which He had lately revealed. Shaykh Sultan, who had been

too ill, at the time of his arrival, to meet the Bab, received one night,

while still on his sick-bed, a message from his |

|

I have heard Shaykh Sultan

himself describe that nocturnal visit: "The Bab, who had bidden me extinguish

the lamp in my room ere He arrived, came straight to my bedside. In the midst

of the darkness which enveloped us, I was holding fast to the hem of His garment

and was imploring Him: `Fulfil my desire, O Beloved of my heart, and allow me

to sacrifice myself for Thee; for no one else except Thee is able to confer upon

me this favour.' `O Shaykh!' the Bab replied, `I too yearn to immolate Myself

upon the altar of sacrifice. It behoves us both to cling to the garment of the

Best-Beloved and to seek from Him the joy and glory of martyrdom in His path.

Rest assured I will, in your behalf, supplicate the Almighty to enable you to

attain His presence. Remember Me on that Day, a Day such as the world has never

seen before.' As the hour of parting approached, he placed in my hand a gift which

He asked me to expend for myself. I tried to refuse; but He begged me to accept

it. Finally I acceded to His wish; whereupon He arose and departed.

I have heard Shaykh Sultan

himself describe that nocturnal visit: "The Bab, who had bidden me extinguish

the lamp in my room ere He arrived, came straight to my bedside. In the midst

of the darkness which enveloped us, I was holding fast to the hem of His garment

and was imploring Him: `Fulfil my desire, O Beloved of my heart, and allow me

to sacrifice myself for Thee; for no one else except Thee is able to confer upon

me this favour.' `O Shaykh!' the Bab replied, `I too yearn to immolate Myself

upon the altar of sacrifice. It behoves us both to cling to the garment of the

Best-Beloved and to seek from Him the joy and glory of martyrdom in His path.

Rest assured I will, in your behalf, supplicate the Almighty to enable you to

attain His presence. Remember Me on that Day, a Day such as the world has never

seen before.' As the hour of parting approached, he placed in my hand a gift which

He asked me to expend for myself. I tried to refuse; but He begged me to accept

it. Finally I acceded to His wish; whereupon He arose and departed.  "The allusion of the Bab that night to His

`Best-Beloved' excited my wonder and curiosity. In the years that followed I oftentimes

believed that the one to whom the Bab had referred was none other than Tahirih.

I even imagined Siyyid-i-'Uluvv to be that person. I was sorely perplexed, and

knew not how to unravel this mystery. When I reached Karbila and attained the

presence of Baha'u'llah, I became firmly convinced that He alone could claim such

affection from the Bab, that He, and only He, could be worthy of such adoration."

"The allusion of the Bab that night to His

`Best-Beloved' excited my wonder and curiosity. In the years that followed I oftentimes

believed that the one to whom the Bab had referred was none other than Tahirih.

I even imagined Siyyid-i-'Uluvv to be that person. I was sorely perplexed, and

knew not how to unravel this mystery. When I reached Karbila and attained the

presence of Baha'u'llah, I became firmly convinced that He alone could claim such

affection from the Bab, that He, and only He, could be worthy of such adoration."

The second Naw-Ruz after the declaration of

the Bab's Mission, which fell on the twenty-first day of the month of Rabi'u'l-Avval,

in the year 1262 A.H.,(1) found

the Bab still in Shiraz enjoying, under circumstances of comparative tranquillity

and ease, the blessings of undisturbed association

The second Naw-Ruz after the declaration of

the Bab's Mission, which fell on the twenty-first day of the month of Rabi'u'l-Avval,

in the year 1262 A.H.,(1) found

the Bab still in Shiraz enjoying, under circumstances of comparative tranquillity

and ease, the blessings of undisturbed association

The mother of the Bab failed

at first to realise the significance of the Mission proclaimed by her Son. She

remained for a time unaware of the magnitude of the forces latent in His Revelation.

As she approached the end of her life, however, she was able to perceive the inestimable

quality of that Treasure which she had conceived and given to the world. It was

Baha'u'llah who eventually enabled her to discover the value of that hidden Treasure

which had lain for so many years concealed from her eyes. She was living in Iraq,

where she hoped to spend the remaining days of her life, when Baha'u'llah instructed

two of His devoted followers, Haji Siyyid Javad-i-Karbila'i and the wife of Haji

Abdu'l-Majid-i-Shirazi, both of whom were already intimately acquainted with her,

to instruct her in the principles of the Faith. She acknowledged the truth of

the Cause and remained, until the closing years of the thirteenth century A.H.,(1)

when she departed this life, fully aware of the bountiful gifts which the Almighty

had chosen to confer upon her.

The mother of the Bab failed

at first to realise the significance of the Mission proclaimed by her Son. She

remained for a time unaware of the magnitude of the forces latent in His Revelation.

As she approached the end of her life, however, she was able to perceive the inestimable

quality of that Treasure which she had conceived and given to the world. It was

Baha'u'llah who eventually enabled her to discover the value of that hidden Treasure

which had lain for so many years concealed from her eyes. She was living in Iraq,

where she hoped to spend the remaining days of her life, when Baha'u'llah instructed

two of His devoted followers, Haji Siyyid Javad-i-Karbila'i and the wife of Haji

Abdu'l-Majid-i-Shirazi, both of whom were already intimately acquainted with her,

to instruct her in the principles of the Faith. She acknowledged the truth of

the Cause and remained, until the closing years of the thirteenth century A.H.,(1)

when she departed this life, fully aware of the bountiful gifts which the Almighty

had chosen to confer upon her.  The wife of the Bab, unlike His mother, perceived

at the earliest dawn of His Revelation the glory and uniqueness of His Mission

and felt from the very beginning the intensity of its force. No one except Tahirih,

among the women of her generation, surpassed her in the spontaneous character

of her devotion nor excelled the fervor of her faith. To her the Bab confided

the secret of His future sufferings, and unfolded

The wife of the Bab, unlike His mother, perceived

at the earliest dawn of His Revelation the glory and uniqueness of His Mission

and felt from the very beginning the intensity of its force. No one except Tahirih,

among the women of her generation, surpassed her in the spontaneous character

of her devotion nor excelled the fervor of her faith. To her the Bab confided

the secret of His future sufferings, and unfolded

to her eyes the significance of the events that were to transpire in His Day. He bade her not to divulge this secret to His mother and counselled her to be patient and resigned to the will of God. He entrusted her with a special prayer, revealed and written by Himself, the reading of which, He assured her, would remove her difficulties and lighten the burden of her woes. "In the hour of your perplexity," He directed her, "recite this prayer ere you go to sleep. I Myself will appear to you and will banish your anxiety." Faithful to His advice, every time she turned to Him in prayer, the light of His unfailing guidance illumined her path and resolved her problems.(1)

|

After the Bab had settled the affairs of His household and provided for

the future maintenance of both His mother and His wife, He transferred

His residence from His own

After the Bab had settled the affairs of His household and provided for

the future maintenance of both His mother and His wife, He transferred

His residence from His own home to that of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali. There He awaited the approaching hour of His sufferings. He knew that the afflictions which were in store for Him could no longer be delayed, that He was soon to be caught in a whirlwind of adversity which would carry Him swiftly to the field of martyrdom, the crowning object of His life. He bade those of His disciples who had settled in Shiraz, among whom were Mulla Abdu'l-Karim and Shaykh Hasan-i-Zunuzi, to proceed to Isfahan and there await His further instructions. Siyyid Husayn-i-Yazdi, |

Meanwhile Husayn Khan, the governor of Fars,

was bending every effort to involve the Bab in fresh embarrassments and to degrade

Him still further in the eyes of the public. The smouldering fire of his hostility

was fanned to flame by the knowledge that the Bab was allowed to pursue unmolested

the course of His activities, that He was still able to associate with certain

of His companions, and that He continued to enjoy the benefits of unrestrained

fellowship with His family and kindred.(1)

By the aid of his secret agents, he succeeded in obtaining accurate information

regarding

Meanwhile Husayn Khan, the governor of Fars,

was bending every effort to involve the Bab in fresh embarrassments and to degrade

Him still further in the eyes of the public. The smouldering fire of his hostility

was fanned to flame by the knowledge that the Bab was allowed to pursue unmolested

the course of His activities, that He was still able to associate with certain

of His companions, and that He continued to enjoy the benefits of unrestrained

fellowship with His family and kindred.(1)

By the aid of his secret agents, he succeeded in obtaining accurate information

regarding

One night

there came to Husayn Khan the chief of his emissaries with the report that the

number of those who were crowding to see the Bab had assumed such proportions

as to necessitate immediate action on the part of those whose function it was

to guard the security of the city. "The eager crowd that gathers every night to

visit the Bab," he remarked, "surpasses in number the multitude of people that

throngs every day before the gates of the seat of your government. Among them

are to be seen men celebrated alike for their exalted rank and extensive learning.(1)

Such are the tact and lavish generosity which his maternal uncle displays in his

attitude towards the officials of your government that no one among your subordinates

is inclined to acquaint you with the reality of the situation. If you would permit

me, I will, with the aid of a number of your attendants, surprise the Bab at the

hour of midnight and will deliver, handcuffed, into your hands certain of his

associates who will enlighten you concerning his activities, and who will confirm

the truth of my statements." Husayn Khan refused to comply with his wish. "I can

tell better than

One night

there came to Husayn Khan the chief of his emissaries with the report that the

number of those who were crowding to see the Bab had assumed such proportions

as to necessitate immediate action on the part of those whose function it was

to guard the security of the city. "The eager crowd that gathers every night to

visit the Bab," he remarked, "surpasses in number the multitude of people that

throngs every day before the gates of the seat of your government. Among them

are to be seen men celebrated alike for their exalted rank and extensive learning.(1)

Such are the tact and lavish generosity which his maternal uncle displays in his

attitude towards the officials of your government that no one among your subordinates

is inclined to acquaint you with the reality of the situation. If you would permit

me, I will, with the aid of a number of your attendants, surprise the Bab at the

hour of midnight and will deliver, handcuffed, into your hands certain of his

associates who will enlighten you concerning his activities, and who will confirm

the truth of my statements." Husayn Khan refused to comply with his wish. "I can

tell better than

That very moment, the governor

summoned Abdu'l-Hamid Khan, the chief constable of the city. "Proceed immediately,"

he commanded him, "to the house of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali. Quietly and unobserved,

scale the wall and ascend to the roof, and from there suddenly enter his home.

Arrest the Siyyid-i-Bab immediately, and conduct him to this place together with

any of the visitors who may be present with him at that time. Confiscate whatever

books and documents you are able to find in that house. As to Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali, it is my intention to impose upon him, the following day, the penalty for

having failed to redeem his promise. I swear by the imperial diadem of Muhammad

Shah that this very night I shall have the Siyyid-i-Bab executed together with

his wretched companions. Their ignominious death will quench the flame they have

kindled, and will awaken every would-be follower of that creed to the danger that

awaits every disturber of the peace of this realm. By this act I shall have extirpated

a heresy the continuance of which constitutes the gravest menace to the interests

of the State."

That very moment, the governor

summoned Abdu'l-Hamid Khan, the chief constable of the city. "Proceed immediately,"

he commanded him, "to the house of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali. Quietly and unobserved,

scale the wall and ascend to the roof, and from there suddenly enter his home.

Arrest the Siyyid-i-Bab immediately, and conduct him to this place together with

any of the visitors who may be present with him at that time. Confiscate whatever

books and documents you are able to find in that house. As to Haji Mirza Siyyid

Ali, it is my intention to impose upon him, the following day, the penalty for

having failed to redeem his promise. I swear by the imperial diadem of Muhammad

Shah that this very night I shall have the Siyyid-i-Bab executed together with

his wretched companions. Their ignominious death will quench the flame they have

kindled, and will awaken every would-be follower of that creed to the danger that

awaits every disturber of the peace of this realm. By this act I shall have extirpated

a heresy the continuance of which constitutes the gravest menace to the interests

of the State."  Abdu'l-Hamid Khan retired to execute his task.

He, together with his assistants, broke into the house of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali(1)

and found the Bab in the company of His maternal uncle and a certain Siyyid Kazim-i-Zanjani,

who was later martyred in Mazindaran, and whose brother, Siyyid Murtada, was one

of the Seven Martyrs of Tihran. He immediately arrested them, collected whatever

documents he could find, ordered Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali to remain in his house,

and conducted the rest to the seat of government. The Bab, undaunted and self-possessed,

was heard to repeat this verse of the Qur'an: "That with which they are threatened

is for the morning. Is not the morning near?" No sooner had the chief constable

reached the marketplace than he discovered, to his amazement, that the people

of the city were fleeing from every side in consternation, as if overtaken by

an appalling calamity. He was struck

Abdu'l-Hamid Khan retired to execute his task.

He, together with his assistants, broke into the house of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali(1)

and found the Bab in the company of His maternal uncle and a certain Siyyid Kazim-i-Zanjani,

who was later martyred in Mazindaran, and whose brother, Siyyid Murtada, was one

of the Seven Martyrs of Tihran. He immediately arrested them, collected whatever

documents he could find, ordered Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali to remain in his house,

and conducted the rest to the seat of government. The Bab, undaunted and self-possessed,

was heard to repeat this verse of the Qur'an: "That with which they are threatened

is for the morning. Is not the morning near?" No sooner had the chief constable

reached the marketplace than he discovered, to his amazement, that the people

of the city were fleeing from every side in consternation, as if overtaken by

an appalling calamity. He was struck

Abdu'l-Hamid Khan, terrified

by this dreadful intelligence, ran to the home of Husayn Khan. An old man who

guarded his house and was acting as door-keeper informed him that the house of

his master was deserted, that the ravages of the pestilence had devastated his

home and afflicted the members of his household. "Two of his Ethiopian maids,"

he was told, "and a man-servant have already fallen victims to this scourge, and

members of his own family are now dangerously ill. In his despair, my master has

abandoned his home and, leaving the dead unburied, has fled with the rest of his

family to the Bagh-i-Takht."(3)

Abdu'l-Hamid Khan, terrified

by this dreadful intelligence, ran to the home of Husayn Khan. An old man who

guarded his house and was acting as door-keeper informed him that the house of

his master was deserted, that the ravages of the pestilence had devastated his

home and afflicted the members of his household. "Two of his Ethiopian maids,"

he was told, "and a man-servant have already fallen victims to this scourge, and

members of his own family are now dangerously ill. In his despair, my master has

abandoned his home and, leaving the dead unburied, has fled with the rest of his

family to the Bagh-i-Takht."(3)  Abdu'l-Hamid Khan decided to conduct the Bab

to his own home and keep Him in his custody pending instructions from the governor.

As he was approaching his house, he was struck by the sound of weeping and wailing

of the members of his household. His son had been attacked by the plague and was

hovering on the brink of death. In his despair, he threw himself at the feet of

the Bab and tearfully implored Him to save the life of his son. He begged Him

to forgive his past transgressions and misdeeds. "I adjure you," he entreated

the Bab as he clung to the hem of His garment, "by Him who has elevated you to

this exalted

Abdu'l-Hamid Khan decided to conduct the Bab

to his own home and keep Him in his custody pending instructions from the governor.

As he was approaching his house, he was struck by the sound of weeping and wailing

of the members of his household. His son had been attacked by the plague and was

hovering on the brink of death. In his despair, he threw himself at the feet of

the Bab and tearfully implored Him to save the life of his son. He begged Him

to forgive his past transgressions and misdeeds. "I adjure you," he entreated

the Bab as he clung to the hem of His garment, "by Him who has elevated you to

this exalted

The Bab, who was in the act of performing

His ablutions and was preparing to offer the prayer of dawn, directed him to take

some of the water with which He was washing His face to his son and request him

to drink it. This He said would save his life.

The Bab, who was in the act of performing

His ablutions and was preparing to offer the prayer of dawn, directed him to take

some of the water with which He was washing His face to his son and request him

to drink it. This He said would save his life.  No sooner had Abdu'l-Hamid

Khan witnessed the signs of the recovery of his son than he wrote a letter to

the governor in which he acquainted him with the whole situation and begged him

to cease his attacks on the Bab. "Have pity on yourself," he wrote him, "as well

as on those whom Providence has committed to your care. Should the fury of this

plague continue its fatal course, no one in this city, I fear, will by the end